By Vibert Cambridge

Vibert Compton Cambridge, Ph.D. is professor emeritus in the School of Media Arts and Studies, Scripps College of Communication, Ohio University. He is also current President, Guyana Cultural Association of New York, Inc. His new book Musical Life in Guyana: History and Politics of Control was published by the University Press of Mississippi in June 2015.

Today’s column is an adapted version of an essay that was first published in the Guyana Cultural Association’s monthly online magazine. (Guyana Folk and Culture, Volume 6. Issues 5, May 30, 2016). Available online at: http://guyfolkfest.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/GCA-MAY.-2016-E-MAG.-FINAL.pdf

Guyana’s Golden Jubilee celebrations are the latest in a history of ceremonies to mark important occasions. Since 1887, with the celebrations for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, governments of British Guiana and, later, the independent state of Guyana have funded or supported programs to celebrate key events. Among the objectives have been to promote and to encourage loyalty and patriotism.

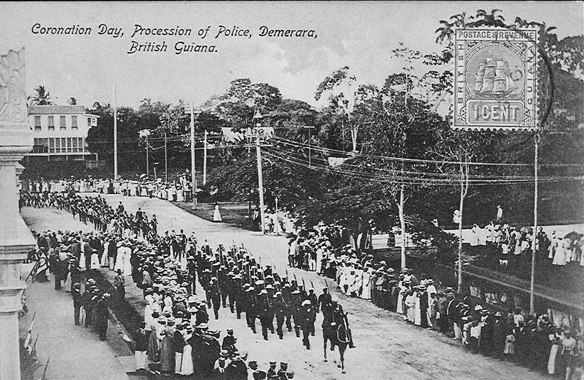

The postcard from British Guiana shows a “procession” of the Police that might have taken place during the Coronation of King Edward VII in 1902.

Some of the events associated with these moments—the decorated and illuminated buildings, ceremonial parades, fireworks, and national exhibitions—were refined during the 1930s and provided a template for the 20th century. That template was evident during the May events of the Jubilee year.

October 1931 marked the centenary of the union of the colonies of Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo to form British Guiana. Despite the economic conditions, an ambitious program was organized featuring decorated and illuminated buildings, the tableau British Guiana 1831−1931, the large model of the Kaieteur Falls at the British Guiana Centenary Exhibition and Fair, military displays, rallies for school children, the publishing of books, feeding programs for the poor, and balls. Among the legacies from the British Guiana Centenary celebrations was Reverend Hawley’s Bryant’s Song of Guiana’s Children.

Despite the ongoing economic crisis, the people of British Guiana commemorated the centenary of the abolition of slavery in 1934. This event was spearheaded by the Negro Progress Convention with marginal support from the state’s coffers. Within the limited means, a program of events was organized in each county. The emphasis was forward-looking. As had been the practice since slavery, efforts at African mobilization in the colony were met with derision. The editorial tone of the Daily Argosy sought to minimize African agency and efficacy in the struggle for the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of enslaved Africans in the colony.

The centenary of Georgetown in March 1937 was more upbeat. Despite the ongoing global economic depression and signs of rising military tensions in Europe, there were signs of optimism in the colony’s economic life. There were improvements in the rice industry as a result of reorganization and improvements in planting methods. The entrepreneur R. G. Humphrey donated $5,000 to launch the development of the Georgetown Pure Water Supply Scheme, which was estimated to cost $120,000. His donation represented the aim to raise the funds for the scheme through local subscriptions in the spirit of “assisting ourselves” that was being encouraged in the face of the persistent economic depression.

Illuminated buildings were among the highlights of the 1935 celebration, representing the Silver Jubilee of the Coronation of King George V. May 1937 marked the coronation of King George VI. From May 8 to 17, 1937, virtually every community in British Guiana held activities to celebrate the coronation. There were illuminated buildings, show window displays, a regatta at the Rowing Club, ceremonial parades, torchlight parades, religious services, fireworks displays, coronation balls, and new musical compositions. By 1937, British Guiana’s broadcasting infrastructure had international connectivity, thus allowing the nation to hear the broadcast of the coronation ceremony from London’s Westminster Abbey live.

The program to celebrate the centenary of East Indian immigration to British Guiana in 1938 was led by the primarily urban British Guiana East Indian Association. This event, like the centenary of the abolition of slavery, also received some state support. This program was also forward looking. In a speech to mark the moment, B.G.E.I.A. president C. R. Jacobs envisaged a future that was primarily rural, idyllic and bucolic—one that contributed to the building of a “greater India in British Guiana.”

So, by the end of the 1930s, British Guiana has established a framework for organizing the celebration of national moments. It is a framework dominated by an active state.

The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II took place in June 1953, a pivotal year in Guyana’s post-World War II history. It was a high point in the struggle for independence. The first election under universal adult suffrage in British Guiana had been held in April 1953. The victors in that election, the People’s Progressive Party, were expelled in October 1953. One of their “sins” was refusing to send a British Guianese delegation to a regional coronation event in Jamaica.

But within the context of this political drama there emerged a movement that began to put the stamp of a homegrown sensibility on state-sponsored celebrations. The planners for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II would eventually morph into the National History and Culture Week Committee (1958). This gave way to the National History and Arts Council; later the Department of Culture; followed by the Ministry of Culture, Youth, and Sport; and currently the Department of Culture, Youth, and Sport.

The post-independence years built upon this history of ceremonies. These moments have on occasion given rise to decisions that have had significant consequences for Guyanese creativity. The meetings of Caribbean artists and intellectuals in 1966 and again in 1970 influenced Guyanese cultural policy. A policy that informed the organization of Carifesta ’72 gave rise to the Institute of Creative Arts, as well as Guyfesta. Carifesta X in 2008 and the launching of the Caribbean Press are other examples.

Clearly, Guyana’s Jubilee celebrations drew upon this history. The national colors made for rich decorations, and Main Street’s illuminations were memorable. An important element in the Golden Jubilee program was the work of the Academic Working Group of the National Commemoration Commission. Its signature events were the Jubilee Literary Festival and the National Symposia Series. These two programs sought to launch an intergenerational conversation on four interrelated questions—Who are we?” What has the journey been like? What can we become? How can we get there? It is felt that through this global conversation, Guyanese will be able to find the commonalities of heritage and aspiration and begin to fashion the steps for building interethnic trust and community.

The Jubilee Literary festival is an international collaboration of Guyanese around the world who have endorsed the goal of improving Guyanese literary life through a distinctive and sustainable literary festival. Jubilee LitFest, this inaugural festival, was conceptualized as a multi-day, multi-event program. It was designed to:

- Raise the nation’s awareness of Guyana’s literary heritage,

- Encourage reading and support literacy,

- Increase the competencies of emerging creative writers in Guyana,

- Improve Guyana’s standing as a destination with a distinctive cultural product, and

- Establish an organization to ensure sustainability of the literary festival.

Gitanjali (Indian Monument Gardens, May 7), Lunch with Peter Kempadoo (Port Mourant, May 14) and Lunch with Mittelholzer (New Amsterdam, May 20) provided opportunities to meet and to explore themes in Guyanese literary life, as well as to explore Guyana’s literary geography. Gitanjali explored Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali in Guyanese consciousness and its role in the Prayers of the National Assembly (also referred to as the Universal Prayer). The celebration of Peter Kempadoo and Edgar Mittelholzer in Poet Mourant and New Amsterdam, respectively, drew attention to the county’s central place in Guyana’s literary heritage. It set in motion a demand for the ongoing exploration of our literary geography. The community engagement, especially the participation of school children, was refreshing.

The Digital Tent (http://guyanadigitaltent.wix.com/2016) is a website that aggregates information about Guyana by Guyanese and non-Guyanese. It was launched on May 2. This upgradable site has been described by former University of Guyana vice-chancellor and current director of culture Dr. James Rose as having “overwhelming implications for research activities.” He anticipates that “as it grows and expands to include new nodes of knowledge, it can become indispensable to the education system.”

The National Symposia Series focused on the four interrelated questions over three days—May 23 & 24 at the Arthur Chung Convention Center, Guyana, and June 5 at York College, Queens, New York. This was another example of international collaboration.

At the end of May, it was clear that many questions have been asked and suggestions offered about the future of the nation. Justifiable questions and comments have been raised about the management of the May events, including questions about ethnic and class inclusion. These are the easy observations associated with a perspective that sees the May events as the culmination of the Jubilee season—the end of a period of reflection and celebration. These observations fail to recognize the initiatives that were launched.

Guyanese youth were engaged in the exploration of Guyana’s literary heritage. Gitanjali was an innovative production by students of the Guyana’s School of Theater Arts and Drama, National Dance School, the Theater Guild, and the Nrityageet Dancers. The production held on May 8 at the Indian Monument Gardens was poorly attended. Were poor publicity and promotion the causes? Was it a clash with the private events of Mothers’ Day? This production ought to be rescheduled. It represents an important contribution of our Indian heritage to Guyanese consciousness. Verse 34 of Gitanjali has inspired the prayers of Guyana’s National Parliament and was the Universal Prayer read at the Jubilee Flag Raising. This event should be repeated again during the Jubilee Year.

In the post-May season, we should build upon the spirit of Port Mourant and New Amsterdam as we move forward with the work to improve literary life in Guyana.

The body of knowledge generated during the National Symposia Series has to be shared and added to. This is work that has to be continued.

The works launched by the National Parks Commission and the Protected Areas Commission must be continued. The rehabilitation and creation of new recreational spaces, such as the scheduled Pineapple Fountain and water park in the Botanical Gardens, are crucial to building a just and caring society. As with all celebrations of national events, there were programs organized by non-governmental agencies.

We saw this with the centenaries of the abolition of slavery and East Indian immigration to British Guiana in 1934 and 1938, respectively. These moments are still celebrated each year with small support from the state. One that stood out for me was the launch of the Philip Moore Artists’ Retreat and Maroon Sculpture Walk—a projected collaboration between the Yukuriba Artists Retreat and the E. R. Burrowes School of Art.

We need to sustain the conversation that was started using all means of communication. The Digital Tent must expand. The intergenerational conversations that were started in Jubilee May must continue. This requires increased investment in the communication infrastructure. It will be a fatal mistake to think this work ended in May 2016.

The organization and management practices that characterized the May 2016 season must be evaluated. There is need for improved interagency coordination among the state players. This is crucial in the media sector. There is a need for private sector and civic groups to work more closely as we move forward in the jubilee year.

The Guyana Cultural Association of New York, Inc., will continue to bridge in the Jubilee Year—its 15th anniversary. We look forward to seeing you in Brooklyn during our annual Folk Festival Season and in Guyana in December for Masquerade Jamboree, a part of the Golden Jubilee Christmas.