Dear Editor,

To those who might have been monitoring the volumes of the annual publication over the years the first curiosity about the 2016 Budget must be the recurrence of agencies whose titles would have changed in 2015.

One obvious and foremost example is that of the Office of the President reduced to the mundanity of a ministry, ie, Ministry of the Presidency, except that the latter has sought to absorb Natural Resources and other former ‘independents’, while in the process still adverting to the diminished Public Service Department as a ministry.

Next, the purportedly eradicated Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development is given much more coverage than the extant Ministry of Communities. Nor is it certain for how long one will see the Ministry of Health, for example, alongside that of Public Health. These and other similar repetitions make for a lugubriously heavy volume.

There continues to be the deliberate (or perhaps unconscious) portrayal of constitutional agencies as budget agencies, namely, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Gecom, Audit Office of Guyana, and others; in addition to the persistent misconstruction of the Public Service Commission and the Police Service Commission as twin ‘agencies’ joined at the hip, so to speak, when the constitution identifies them as separate and distinct commissions.

A further pause for examination is the view that the Georgetown Public Hospital Corporation should continue to be embedded as a budget agency, even though it was deliberately registered by a former Minister of Health under the Public Corporations Act, like GuySuCo, say. One significant implication of this organisational travesty is that since the corporation is treated as ‘public service’, it has reduced its specialists and other trained practitioners to the status of the preponderancy of contractees in the general public service. So those groups of skills are grievously under-paid and demotivated, a condition which from reported evidence impacts less positively on productivity than their patients expect.

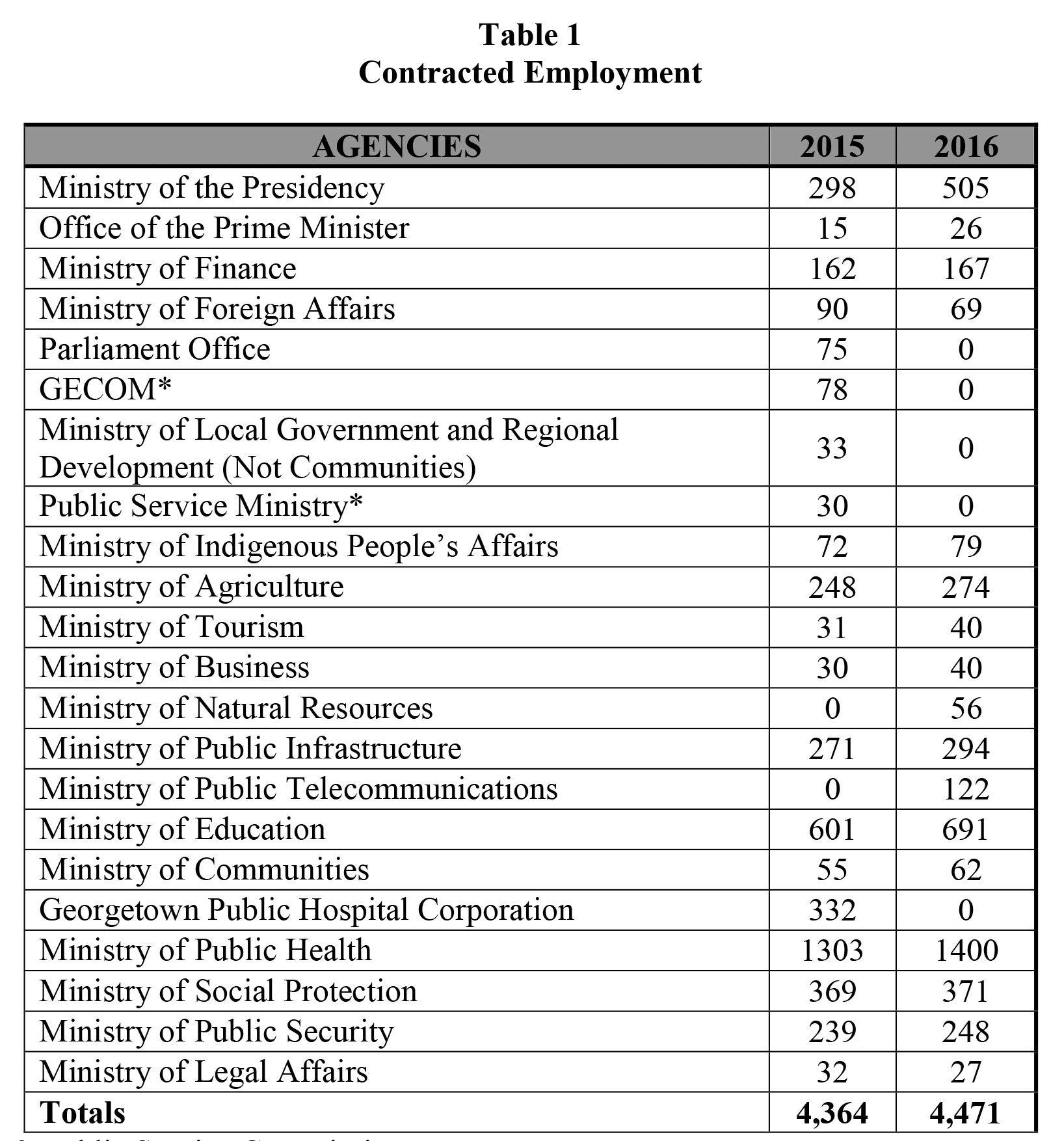

But the situation is further compounded by the incidence of ‘contracted employees’ not only in that institution, but across the respective budget agencies. An immediate contradiction however is seen in Table 1 below wherein miraculously GPHC’s 332 contracted employees have disappeared from the 2016 column alongside. Have their contracts been terminated, and at what cost?

* Police & Public Service Commission

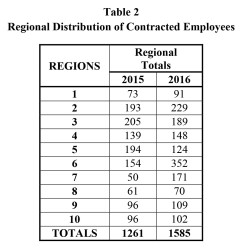

And as a matter of interest Table 2 below shows the comparable numbers of Contracted Employees in the ten Regional Administrations, in respect of years 2015 and 2016 – an increase of 324 or 20.4%

Recruitment of contracted employees has progressively increased from as far back as 2010, indicative of a presumption that either contracts are continuously renewed, or there is no specified duration – a notion that makes nonsense of the descriptor ‘contracted employees’, and one that reflects either ignorance of the standard employment procedures, or (not unlikely), an indulgence in deception, particularly since the justification is hardly seen in any substantive developmental projects.

Scarcely anyone seems to have noticed the wide range of authority of regional executive officers over four to five programmes – Agriculture, Administration & Finance, Education, Public Works, Health – more likely a wider coverage than some permanent secretaries.

Interestingly enough the salaries are hardly comparable. But that is another matter!

Of perhaps of greater concern is the substantial amount of gratuity paid – at 22.5% of monthly salary every six months, adding up to a virtual salary increase of 90% over a two year period.

Wherever anybody (including the unions) turns, only a most comprehensive national job evaluation exercise can resolve the massive compensation management dilemma in which a confused public service structure is entrapped.

Yours faithfully,

E B John