Saluting Tchaiko Kwayana

By Nigel Westmaas

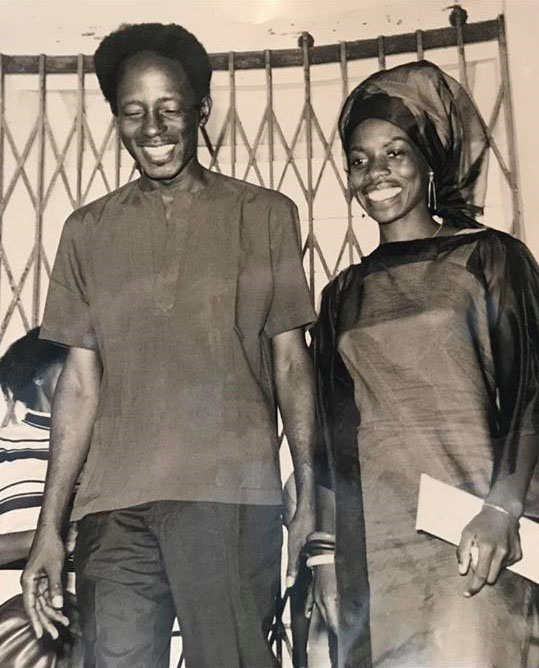

Tchaiko Ruramai Kwayana was an educator, pan-Africanist, and civil rights activist. Born and raised

Her journeys were augmented by her first published work “Black Pride? Some Contradictions” in the Black Woman (1968) which advocated “international travel for increased enlightenment”. Tchaiko eventually travelled to Bahia, Brazil and on her return stopped in Guyana in 1968 where she met Eusi Kwayana (then Sydney King). Tchaiko was a key organizer of the seminar of “Pan-Africanists and Black Revolutionists” held in Guyana in 1970.

In Guyana, Tchaiko was a member of ASCRIA and eventually the Women Against Terror organisation fighting the Guyana dictatorship at the time.

In 1973 Tchaiko and Eusi Kwayana published Scars of Bondage, an assessment of slavery in Guyana and the Americas. In the prologue the Kwayanas stated:

“Readers will notice that we stand very strongly for African value systems and seek to make this point as often as we can for several reasons. The world generally agrees that Africa has ‘nice’ dances and music, but not that Africa has civilisation, a mind, a morality that is supremely its own. We are not speaking here of some present day corrupt African cities in most of which confusion reigns under European political systems. We are speaking of the collectivist Africa of the past and present which has many lessons of principle for a world based on national and international class exploitation.”

Tchaiko remained in Guyana until 1982 when she returned to the USA mainly for economic reasons.

In the USA Tchaiko resumed her role as an educator while involving herself in organisations such as LAD (a leadership training organization in San Diego). In Atlanta she co-founded Helping Uplift Guyanese (HUG) and co-founded the Sankofa Bird project, a “communities based Humanities program” that also assisted AIDS patients.

She was awarded the title of “Queen Mother” by the Association for the Study of Classical African Civilizations. Both Tchaiko and Eusi Kwayana were members of the Langston Hughes Poetry circle (Tchaiko knew Langston Hughes personally).

Eusi Kwayana eventually left Guyana to be with his family in 2002.On reflecting on his move to the United States Kwayana states, “I was away from them for so many years and they were the ones sustaining me….I was never really the breadwinner. My wife has a lot of courage and strength and I am just happy to be with her now.”

Remembering Tchaiko: Rampersaud Tiwari

Tchaiko Ruramai Kwayana was a truly remarkable woman and a great teacher who made our world a better place. Arriving in Buxton in 1968, she immediately immersed herself in the community culture of the village. She was a favourite of the women and children; and indeed of all with whom she related as she was a soul for a wider humanity. She was destined to connect with Eusi Kwayana (formerly Sydney King). a native of Lusignan, a neighbouring sugar plantation community. to whom she was married in 1971 in accordance with the ancestral spiritual matrimonial rituals of the Yoruba people of Africa, her motherland. Eusi was himself also an outstanding educator and teacher who had established his own private school in Buxton and named it as County High School. Tchaiko was a teacher in the school for 13 years. She and Eusi lived in Eusi’s family home at Buxton Middlewalk South where they had three children including twins, one of whom died in infancy. Tchaiko is survived by a daughter Iyabo and two sons, Kofi and Kwame.

An ideal woman of fine enduring spiritual and secular values, Tchaiko was dedicated to the welfare of her family and community, especially children with whom she shared her passion for good books, stories, music and song. She has left an everlasting legacy of memories of shared experiences in struggle, sacrifice and success.

A Spirit Taking World Michelle Yaa Asantewa

There’s a refrain, seemingly cultural, that persisted during my first return to Guyana in 1994 – ‘is a spirit taking world.” I didn’t immediately take to the expression, especially as I found its use common among men I believed used it as a hustle. Women used it, which I likewise distrusted, sensing there was some expectation behind it. I believed the ‘spirit taking’ had to be reciprocal. But rarely was it so, hence my suspicions about its overuse. A few mornings ago, I opened the email from Elder Eusi Kwayana to see only the subject heading ‘Tchaiko passed away about 4.am today,’ 6th May.

I cried, then, as though I had personally and intimately known Elder Tchaiko, as though we were blood related. Part way through my sobbing I wondered why I was reacting that way, why I was so saddened by the news. I had never met Elder Tchaiko – our only communication had been through emails and Facebook messages. She had, most recently, sent to my care a box of books by her husband Eusi (A New Look at Jonestown) for me to distribute. So much of those communications were in connection with relaying messages to or from Elder Eusi, whom I had met some years ago, and with whom I’ve since had many virtual conversations; he provided a preface to my book on Komfa.

It is a spirit taking world. I realised after gathering my emotions that I felt connected to Elder Tchaiko through spirit, since we’d never met in person. I had by now searched Facebook for more details of her passing, particularly from her son, Kofi, with whom I am friends on Facebook. His page, his sister’s Iyabo’s and their mother’s were full of beautiful tributes from all over the world, expressing deep condolences, acknowledging the greatness of the soul that had ascended. Some mentioned how she had inspired them through her teaching, the special way she was able to touch a part of them no matter where in the world she had travelled – Nigeria, Guyana, Surinam, Mexico. Her face, bright, honest and gentle beamed from the many pictures being shared; each of them revealing a woman confident in her skin, aware of her purpose, aligned with her spirit, so that it would naturally be impossible not to feel blessed or inspired by being in her company. I scrolled the images, enchanted by how well she donned those traditional outfits – her locks carefully wrapped to create colourful crowns that elevated her natural beauty, her skin always glowing.

I knew Elder Eusi had met my grandparents. I knew the family used to visit my grandparents’ home in Seafield Village, No.42, West Coast Berbice back in the 1970s. My mum had always told a tale I took for granted until we learnt of Elder Tchaiko’s passing. When my grandfather, Daniel Ezekiel David (known as ‘Aaron David,’ and ‘Topan’) passed in 1978, the Kwayana family were there. At the time there were three boys, including twins, whom my grandparents adored; our well-known family tale was that they were like surrogate grandchildren. The story goes that at the funeral one of the children was so upset he jumped into my grandfather’s grave. In 1979, one of the twins died. It is believed this was the child who had leapt into the grave. Because so many real life events easily become mythic, I never consciously absorbed this narrative. My mum was relaying it from what she had heard (she had by this time migrated to England) as she was not herself at my grandfather’s funeral.

On hearing the news of his mother’s transition, I have communicated with Kofi Kwayana, who hadn’t until now realised there was a familial connection. He said he remembers clearly the entrance to my grandparents’ home; he remembered vaguely the story about what happened at the funeral. My mum became tearful, as she again relayed the story for both mine and Kofi’s benefit. In conversation with his father, Kofi learnt from him of the book on Komfa I wrote and of my ancestors in Seafield, who feature in Elder Eusi’s latest book – The Legend: Post Emancipation Villages in Guyana: Making World History.

It is a spirit taking world. During mine and Kofi’s Facebook messaging chats, I became aware that I must have met the family. You see, I was also at my grandfather’s funeral. I was about eight. I know, from stories, that it was a big thing in the village; he had been the village chairman, counselling villagers squabbling over petty issues and trying to equitably manage the community’s affairs. I loved this old man (some also called him ‘ole Manzee’). His was the first death I remember being affected by as a child; my father’s followed two months later, fatefully on 18th November when many perished in the Jim Jones mass suicide. I was so upset by my grandfather’s death I only remember part of the experience. They had his body in a room for viewing – then the house had no bottom, stairs back and front led upstairs to the house. My elder cousins feared his corpse but I went into the room and put powder on him, as the adults were doing. I remember not being afraid of him. Though I was in that moment sharing grief with others, among them the young Kwayana boys and their parents, I cannot remember seeing them. I put this down to a deliberate blocking in memory brought on by the loss of my grandfather.

And so it is many years later I would discover the spirit of Elder Tchaiko who always had time, in a life evidently busy, to give to others. It is inspiring that this young girl found her way from Georgia to Guyana, having internalised the love of travel from her parents, both educators as she was, met and married her soul mate, pursued with him a life dedicated to liberation of Africans (in truth the human family) girded by the philosophy ‘I am Somebody.’ In a YouTube video bearing this principle as its title, she says she was struck by the determination of Nigerians (where she had taught prior to going to Guyana) and Guyanese who ‘never felt there was anything they could not do,’ that ‘nothing is too difficult’ to do; everything could be ‘conquered,’ all obstacles overcome. She saw this as an empowering affirmation that could transform the aspiration of school children. When she met Elder Eusi she was introduced to an effective ‘bottom house’ schooling system, a means of self-determination she found inspiring. She used these experiences to return to America with a stronger sense of the kind of educator she would be; how more effectively she could transform the lives of young people; enabling them to identify their own strengths.

In those many images floating online of this Elder, sister, mother, aunty, teacher and cultural ambassador, I see a rare spirit. And although I, like so many whom she touched with her gracious spirit, am sad to hear of her passing I know the candles lighting her path to transition will be many and bright.

The ‘Celebration of the Life’ of Tchaiko Ruramai Kwayana will take place on Tuesday 16th May, fittingly at the Shrine of the Black Madonna, 960 Ralph David, Abernathy, Atlanta, Georgia. Services will be conducted in accordance with the customary rules of burial of her African ancestral Yoruba heritage. May Tchaiko Kwayana’s sacred soul be re-united and rest in peace in the spiritual realm of her departed ancestors.