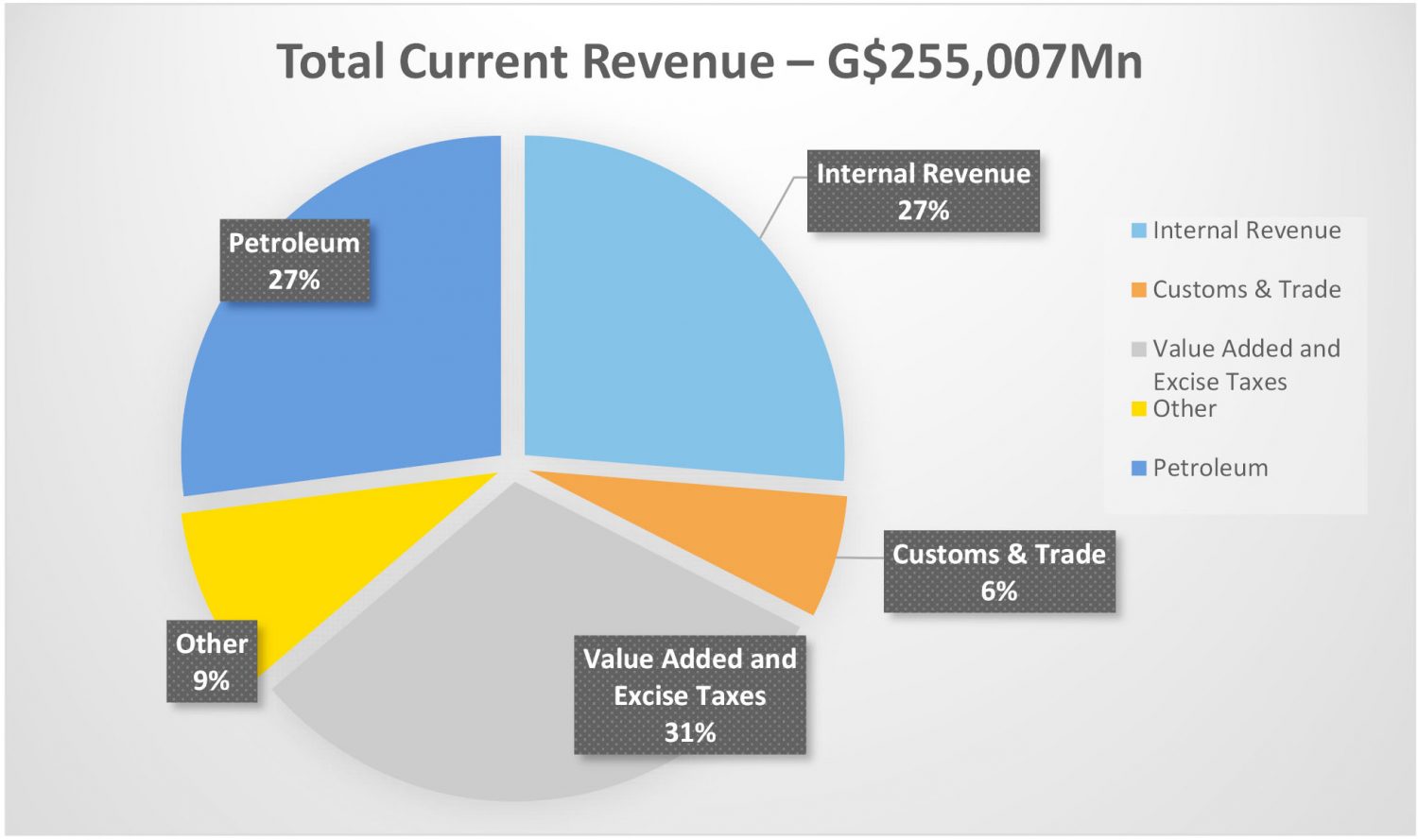

It is now just over the halfway stage of the life of the current Parliament. In about the same time into the future, Guyana will join the club of petro states, catapulting to No. 9 on the list of oil producing countries, using the metric of per capita barrel of oil per day. Ram & McRae projects that in the first full year of production, the share of government revenue from petroleum will exceed twenty-five per cent. This is huge but not unusual among oil producing countries.

Budgeted Current Revenue for 2017 – illustrative impact of Petroleum

Of course, Guyana has long been a producer of non-renewable resources earning not insubstantial revenues and foreign exchange in the process. For decades, the revenues from those sectors were substantially collected not by the central government but by statutory bodies such as the Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC), the Guyana Gold Board and the Guyana Forestry Commission, each acting both as regulator and collector of taxes and fees. These moneys therefore found themselves in the Consolidated Fund by this indirect and inefficient route.

In the two and one half years since the announcement of the largest oil find in 2015, there has been no concluded parliamentary intervention in the sector, as a result of which the governing regulatory and fiscal framework for the petroleum sector is governed by two petroleum Acts, one passed in 1939 and the other in 1986, industry specific regulations passed in 1986, and the Income Tax Act. Meanwhile a Petroleum Commission Bill was tabled in the National Assembly and referred to a Parliamentary Select Committee. The Minister indicated that this is a priority for 2018 but there are likely to be substantial changes to the Bill if it is to serve the function of overseeing the oil sector within a framework of transparency and accountability.

The financial provisions of that Bill are not only opaque but are silent on the matter of profit oil which will be the largest single source of revenue from upstream petroleum operations. Paragraph (4) (b) of Clause 4 of the Bill setting out the responsibility of the proposed Commission speaks only of “the collection and recovery of all rents, fees, royalties, penalties, levies, tolls and other charges”. This does not appear to include the share of profit oil which Guyana will receive.

Under the terms of the existing Petroleum Agreements, oil companies will pay no Corporation Tax but they will receive a credit for deemed Corporation Tax paid. Presumably the Guyana Revenue Authority will make a book entry for, and treat the tax as paid over to the Consolidated Fund. In the absence of an amendment to Article 216 of the Constitution, the proceeds of profit oil less the deemed Corporation Tax, will also be credited to the Consolidated Fund. As the law currently stands, the entire proceeds from the oil companies will be available to the Legislature and the Executive to appropriate for spending. That is clearly unacceptable and unfair to future generations when the wells are exhausted and there are no oil revenues.

Recently, Guyana has become a magnet for consultants and investment specialists offering gratuitous advice to Guyana on everything from oil refineries to establishment of a Sovereign Wealth Fund. By now, every Guyanese is aware that the primary functions of such a fund are the stabilisation of the country’s economy through diversification, and the setting aside of revenues for future generations. Such goals are not only noble: they often make economic and practical sense. For Ram & McRae therefore it is not a question of whether or not Guyana should have a SWF, it is clear that it should. That is the easy part. The hard part is to recognise that a Sovereign Wealth Fund, however described, is part of the wider issue of revenue management, including resource governance.

The Resource Governance Index for 2017 (Governance Index) covering eighty-one countries across the world, distinguishes the successful extractive industries countries of which Norway, Canada, Chile and Botswana are held up as models, – from those that have been plagued with the “resource curse” or the Dutch Disease, of which neighbouring Venezuela, Nigeria, Myanmar and Uzbekistan are unfortunate poster children. The distinction between these two group of countries lies in the establishment and adherence to sound laws, policies and practices conducive to value realisation, revenue management, and an enabling environment.

The first component – value realisation – covers the governance of allocating extraction rights, exploration, production, environmental protection, revenue collection and state-owned enterprises. The second – revenue management – covers national budgeting, subnational resource revenue sharing, and sovereign wealth funds. The index’s third component assesses each country’s enabling environment, or governance framework, made up of Open data, Political stability and absence of violence, Control of corruption, rule of law, regulatory quality, government effectiveness and voice and accountability.

Guyana is not among the eighty-one countries covered in the Index. So while it would be meaninglessly idle to speculate where the country would have ranked in the Index, it would still be useful for our policy makers to take note of its findings and assessments and to consider the examples to follow and the lessons to be avoided. After all, only four of the countries, or one out of every twenty, is considered “good”, i.e. has established laws and practices that are likely to result in extractive resource wealth benefiting citizens. Another twelve countries were found to be satisfactory, i.e. have some strong governance procedures and practices, but some areas need improvement. In those countries, it is reasonably likely that extractive resource wealth benefits the citizens of these countries, but that there may also be costs to society.

The majority of the countries – around sixty – are rated as “weak”, or “poor”, with a mix of strong and problematic areas of governance, or practically few respectively, procedures and practices to govern resources. Finally, there are ten countries which are rated as failing. In these countries, there is an absence of any governance framework to ensure resource extraction benefits society. In these countries, it is highly likely that benefits flow only to some companies and the country’s elite.

But the Index is not without some significance to Guyana. Ram & McRae has compared the rankings in the Governance Index with those in another major Index in which Guyana does not fare too well – the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index. A comparison shows that those countries which fare poorly on the Corruption Index also fare poorly on the Governance Index. Norway, Chile, United Kingdom, Canada and Australia and the USA rate highly in both Indexes but without exception, every country found at the bottom of the ladder in the Corruption Index is among the worst in the Governance Index as well.

Guyana is among the countries with a poor showing in the Corruption Index which may portend a poor showing in the Governance Index as well, whenever it is included among the petroleum and extractive industries Governance Index. While the Government successfully applies for membership of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), it is adamant about not disclosing its petroleum agreements, offering facile excuses which not only make the country seem backward but can make corruption so much easier.

Writing in Oil, Gas and Mining, a World Bank 2017 Publication, Peter D. Cameron and Michael C. Stanley noted that while good practice in resource management is increasingly recognised, the experience in most resource-rich states “has not been especially encouraging” and that there are continuing problems in the implementation of sound resource revenue management. The writers identified three resource constraints faced by developing countries with recently discovered large scale natural resources and four main challenges. With minimal exception, all seven constraints and challenges apply directly to Guyana, and are therefore worth repeating.

Constraints:

- A scarcity of capital, with an interest rate higher than the global rate, and limited access to international capital markets, possibly as a result of the country’s credit rating.

- An undersupply of public infrastructure.

- An investment climate that lacks incentives to private investment.

Challenges:

- Volatility and uncertainty of revenue receipts: Prices for commodities have defied the most informed price forecasting and have been stunningly unimpressive since the oil war of the seventies. Given the fungibility of money, significant oil revenues will affect both the revenue and capital budgets and could easily stop otherwise desirable projects midstream.

- Absorptive capacity: Where revenues are spent at once, the price of plant machinery and equipment that enable production, such as transportation, will be driven up. Future non-resource sectors may appear unattractive by comparison and cause sectors even with good prospects to be neglected, reducing learning and future growth.

- Exhaustion: The products, being non-renewable, raise a conflict between short-term revenue maximisation and inter-generational interests. Both the PPP/C and the APNU+AFC have chosen to give licences over most of the off-shore areas currently under the country’s international jurisdiction. If all of these are explored and exploited simultaneously exhaustion will take place sooner rather than later making the decision between consumption and savings all the more critical.

- Undetermined ownership: If the provisions of the Constitution regarding the power of the Regions to raise money (Article 76) and the allocation and garnering of resources by local democratic organs (Article 77A) were taken seriously by the Government, the question of ownership of natural resources and the disconnect between simultaneous resource wealth and individual poverty within regions would have posed real challenges. It does not appear that the Government or the Opposition understand the significance and implications of these constitutional provisions.

Halfway into its term, this Administration has not demonstrated that it sufficiently understands the law and issues regarding the petroleum sector and that it is capable of managing the petroleum resources. Most of the resources have been allocated or reallocated under archaic legislation by Ministers whose competence in the sector is unconvincing.

The Minister of Finance announced in his Speech the establishment of a Sovereign Wealth Fund, starting in 2018. Of course oil revenues do not arise until mid to late 2020 so there will be no petroleum money to put into the Fund. Maybe as a test run, the Minister of Finance and the Minister for the petroleum sector might wish to consider starting with a gold, diamond and bauxite fund and by the time oil revenues come in the country will have worked out the kinks.