Apparently, the party took the president at his word when in his address at the opening of the 11th Parliament in June 2015 he expounded: ‘Your Government envisages the elimination of one-party domination of the government; the enhancement of local, municipal and parliamentary democracy; the elimination of ethnic insecurity.’ This has obviously not happened in keeping with the expectations of that party. Thus, believing itself and its co-leader, Dr. Rupert Roopnaraine, to have been shabbily treated, the party claimed that ‘These improved results seem to suggest that the President may have acted prematurely in removing him from that ministry.’ The party felt that Dr Roopnaraine was not given a full chance to carry out the vision he had for the ministry. Furthermore, ‘It is now open knowledge that the minister was removed for lack of performance.’ (President should publicly acknowledge Roopnaraine’s work, WPA says. SN: 06/07/2017).

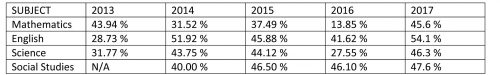

The emergency funds were allocated to the Ministry in 2016 and one does not have to be a genius to observe that, given the variability in the numbers in the above table, what best explains the increase in 2017 is a return to the historic norms and what most begs explanation is the steep fall to 13.85% that occurred in the first year of the APNU+AFC regime. Maybe the decrease was due to distractions caused by the 2015 elections, the change of a government that had been in office for more than two decades and the inexperience of the new players. Whatever it was, one cannot properly blame the present government as education outcomes should not be judged over such a short period. It must be said, though, that if the regime wants to take the credit for one year of an intervention that has essentially only taken us back closer to the historic norm, it must be prepared to take the blame for the decline that occurred in the first year of its government.

True, calls for us to make education management nonpolitical usually miss the point that education outcomes are largely determined by education financing, i.e., budgetary allocations, and those are not likely to ever become nonpolitical. But the MOE should take care that it does not come to appear so blatantly politically partisan!

The fact that at the time of removing Dr. Roopnaraine, the government also ‘announced that a department is to be created within the ministry (of the Presidency) to oversee innovation and reform in the education sector’ suggests that a performance-related element may have been involved in the removal. However, if education outcomes cannot be sensibly judged over too short a period, it might be more prudent to partly judge performance by way of inputs.

I have taken issue with some of the recent decisions being taken by the MOE without what appears to be any proper study, and given the numerous consultations that the MOE is structurally obliged to perform because it has consistently been producing strategic plans since about 1985, I doubted very much that a new inquiry would produce anything substantially new (SN: 20/04/2016 to 04/05/2016). Indeed, widespread national consultations paid for by the World Bank were completed in about 2005 to form the basis of crafting the new Education Bill, which is still in incubation and the fast-tracking of which has been one of the more important recommendations of the just completed national inquiry!

However, unless Dr. Roopnaraine was deliberately bucking cabinet decisions, he cannot be wholly blamed for the existence or not of important education policy decisions having to do with innovation and reforms. An important aspect of cabinet government is the establishment of subcommittees that include technicians from a given ministry. The general direction of the ministry and important policy decisions are usually filtered through these committees, which will, if the decision is sufficiently important, report the matter to cabinet.

This being the case, the realists would have us believe that although presented in a performance-related context, Dr. Roopnaraine actually ran afoul of the notion of cabinet collective responsibility. Particularly since the issue had to do with his ministry, his major offence was that he was not a sufficiently staunch defender of what was clearly a cabinet decision to levy VAT on education. Indeed, this might later give rise to more problems if the regime has no intention of removing the VAT!

In relation to the issue of education reform, there is hardly a country in the world that is not persistently reforming its education system – to a point I believe it safe to say that in education, reform is education policy making. We expect that a modern ministry will be responsible for designing, making, monitoring and facilitating policy and policy adaptation and generally representing its sector nationally and internationally. Our education system is designed to leave policy execution to the regions and at the basic level ideally to schools with autonomous management to, if nothing else help to induce parental participation and proper school management, including teacher discipline.

Presidents do have sectoral advisors overseeing small departments that keep the big picture in mind and focus on specific troublesome areas. However, as I understand it, the outcomes from these are usually inputted into the planning process of the central ministry. Therefore, given the nature and possible scope of education reform and innovation, someone needs to say precisely what kind of process and organisational demarcations are envisaged in the education sector under this new arrangement. The worst thing that could possibly happen to the sector is for the government to leave these demarcations amorphous, thus allowing more space for a decapitated MOE to busy itself willy-nilly intervening in school management and giving rise to chaos nation-wide.

henryjeffrey@yahoo.com