“Who drew the dicks?”

This is the narrative hook on which Netflix’s new mockumentary comedy “American Vandal” rests. We can readily admit that this hook is not just a bizarre one but one that seems almost immediately precarious. Humour about phalluses is not new. It was not new in the nineties with Jim Carrey. It was not new in the renaissance with Shakespeare. But there’s an unwholesomeness to the idea of the dick joke that makes it seem lazy. Too easy. Unearned. From its opening I was as intrigued as much as I was wary. How could the show develop from such a premise?

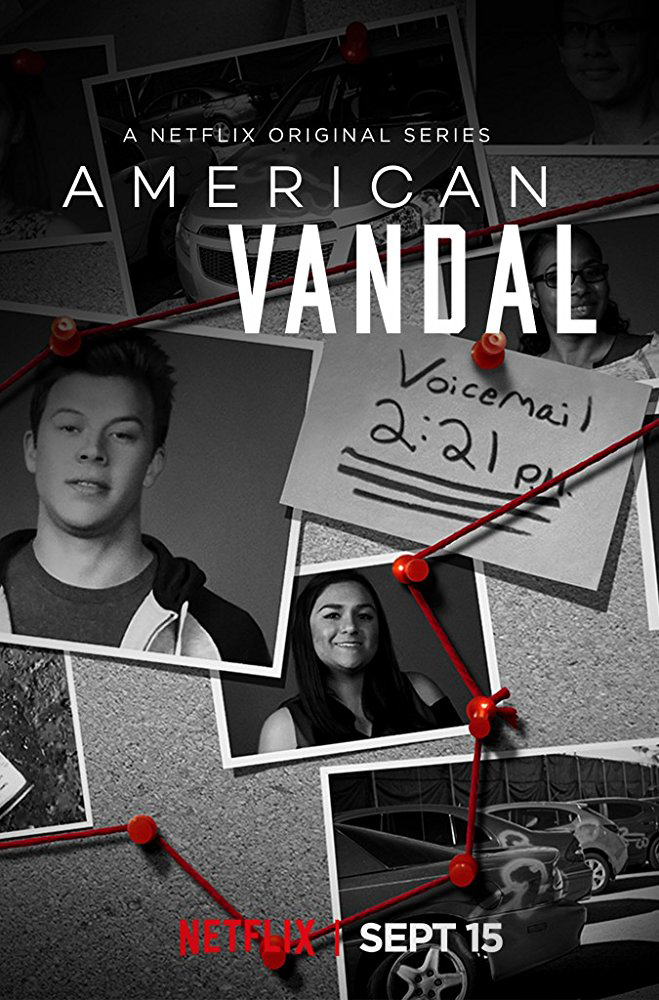

In an American high-school parking lot, the cars of 27 teachers are all spray-painted with a single, red penis on each. Resident class clown Dylan Maxwell is accused of the vandalism and expelled for it. He is the obvious assailant. Except, what this mockumentary supposes, in the vein of true crime investigative works, like Serial or Making a Murderer, or any true crime drama, is that, perhaps he did not. And, so “American Vandal” begins. Baldly and unrepentantly as a spoof.

But, sometimes, the familiarity of something as casual and silly as a dick joke rewards us when we invest in it. I happened upon “American Vandal” by mere happenstance. The silliness of its ad campaign piqued my interest and I decided to investigate, for purely professional reasons. Three episodes in and I could not wait for the resolution. I watched the entire eight episodes (between 30 and 45 minutes each) within 24 hours. “American Vandal,” as much as it spoofs or recreates or copies the true crime world that compels so many of us, is also something wholly itself. An intriguing and potent look at the school system and teenage interaction.

Media about academia is one of my favourite genres. And within that genre, “American Vandal” features my favourite subdivision: media about academia that depends on interaction between students and educators. I have a professional and personal affection for academia, its effects and its influences. “American Vandal,” speciously built on that solitary, recurring, dick joke, builds up to a final arc about institutionalised limitations and issues within academia that is resolved with aplomb in a final episode that features three whiplash moments that make for great television.

Dylan, the accused, is our main

character but our story depends on Peter Maldonado, the savvy, techy, wannabe filmmaker who decides to use the incident as a chance to work on his documentary skills. “American Vandal” the series is a literal recreation of the documentary that Peter would make, but with excellent production values no high schooler would have. As Peter becomes beguiled by the attention his documentary gets, his allegiance falters – is he trying to exonerate Dylan, find the truth, or just get attention? The series, for all its humour, never avoids the underbelly of teenage selfishness that affects the interactions of these characters.

Last weekend, the Television Academy held their awards. The drama, comedy and limited series categories were each won by shows about the female experience (“The Handmaid’s Tale,” “Veep,” and “Big Little Lies,” respectively). Amidst significant wins for Riz Ahmed (first male Asian actor to win, or a double win for African-American actor, writer and director Donald Glover), the political statement of the wins seemed significant. I’ve said before here that the fraught nature of socio-political issues currently makes it impossible not to read politics, or cultural critique into anything we consume. Television is no different, and a show as bizarre as “American Vandal” is no different. Its playfulness reaches the importance of satire. The satire works because the question of what is the main victim of that satire is open for debate: The justice system? The school system? Teenage codes of conducts? Masculinity? Politics? Adults? Take your pick.

As the show kept building up, I kept waiting, expectantly, for the moment when the conceit would give out. I kept waiting for the moment when creators Dan Perrault and Tony Yacenda would turn to us, the audience, and shrug as if to say – okay, the conceit can’t go on forever. Except, it can. And it, does. The show never does let up on its onslaught of the phallus. It never gives up that dick joke. It toes the line between taking its characters and its bizarre world seriously all the while realising always the need to balance its humour. The show leans in, heavily, on the silliness. “American Vandal” is deeply weird, and the phrase “your mileage may vary” is about as apt about this show as any that you’ll see. You will see many drawings of dicks, and you will hear the word dick very often. You will witness a YouTube prank called “baby farting” which is not what it sounds like. It really leans in, heavily, on the teenage (American) high school boy as a vessel for gross repulsion. Its episodes titles, themselves, mirror the jokes. The excellent “A Limp Alibi” is my favourite. But perhaps because of all that “American Vandal” is intriguing and oddly, moving. Yes, moving.

It’s anyone guess what anyone else will take out of it. I like to think of those 27 dicks as a Rorschach test via a spray paint can. Stare into its red outline and you might see Freudian phallic stage, America’s obsession with childish humour, masculinity under siege or something more profound. Whatever you see, be open to the possibility of more, though. “American Vandal” is no mere exercise in low hanging fruit. This extended dick joke has much to offer.

Have a comment? Write to Andrew at almasydk@gmail.com