The Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) with ExxonMobil is generous to the investor and a series of loopholes exist, such as the treatment of interest expense, which could be abused and further limit benefits to Guyana.

These are some of the findings of an expert team from the Fiscal Affairs Department (FAD) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) which undertook a mission at the request of Minister of Finance, Winston Jordan. It doesn’t state the date of the request but the team was here from July 10-21, 2017.

A report dated November 2017 was submitted to the government but has not been released to the public. The Sunday Stabroek has seen a copy of it.

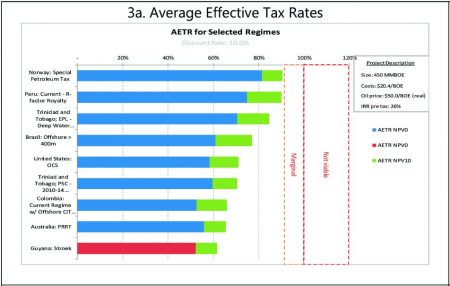

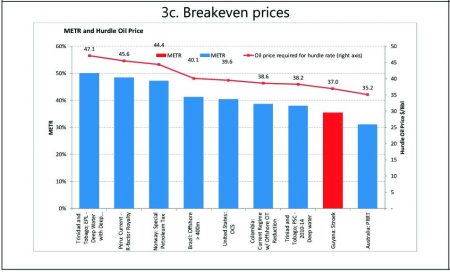

A key finding of the report after assessing similar PSAs from around the world is that the Stabroek PSA has the lowest Average Effective Tax Rate (AETR) of “government take”.

“This result confirms that the terms offered in the agreement are generous to the investor, but were probably required to attract investment at a time in which little was known about the geological prospects of the country. Moreover, some of the countries with the highest AETRs in the sample, such as Norway and Trinidad and Tobago, are mature and well-established producers that have had the opportunity to fine tune their fiscal regimes over time”, the report said.

That finding in the IMF report will likely raise serious questions about what is contained in the entirely new agreement that the government struck with ExxonMobil’s subsidiary Esso Exploration and Guyana Production Limited (EEGLP) in 2016. That agreement the Granger administration had refused to release for months. It recently said that it would release it this month but has thus far not done so. When he spoke about the 2016 agreement, Natural Resources Minister Raphael Trotman would only say that it had just been “tweaked” and that there were no major changes. While the PSA struck in 1999 with the Janet Jagan administration would have been seen as generous, it came at a time when no oil had been found here. By contrast by 2016, the Liza oil well was a world class find and it was believed that other potential huge finds existed in the Stabroek Block which was later borne out. This should have strengthened the negotiating hand of the Guyana team.

Which government official or team then negotiated an entirely new agreement with ExxonMobil and whether it took account of the deficiencies of the 1999 pact will likely raise serious questions. The government is already battling accusations of ducking a US$18m signing bonus from the 2016 PSA but the IMF report points to far more serious issues that should have been addressed in a new PSA. Stabroek News, commentator Christopher Ram and others have asked questions about who negotiated the 2016 agreement. The government has been silent on this matter.

The IMF team did not have access to the 2016 PSA that was concluded by the government with EEGLP. It said that it relied on publicly available information and third party data. It stated that while the government and industry stakeholders say that the PSA is confidential the model PSA does not appear to apply to the agreement itself. The FAD team said that confidentiality appears to pertain to petroleum data, information and reports obtained or prepared by the contractor in relation to the contract area covered by the PSA. It said that the authorities may wish to seek legal advice from the Attorney General on the interpretation of the clause but that going forward it would be preferable to make PSAs public. The FAD team is the latest voice to state that such PSAs should be public, contrary to excuses that have been offered by the government.

“Disclosure of agreements, especially within government, is essential for a coordinated and effective management of the sector. Disclosure of fiscal terms provide the basis for a more informed public debate and accountability. Finally, contract transparency may also allow governments to negotiate more effectively within a level playing field”, the report posited.

The FAD report then went through the key aspects of the PSA utilising specific references to the terms of the Stabroek block agreement that are available.

In respect of royalties, the FAD said that it understood that the royalty rate for the Stabroek PSA was originally set at one percent and was paid out of the government’s share of profit oil. However, as part of the 2016 renegotiation the royalty was removed from the pay-on-behalf system and the rate increased to two percent on an advalorem basis. The mission says it understands that the re-negotiated royalty is now levied on the gross value of oil and gas produced and saved from the contract area.

“With rates set at modest levels, royalties have the advantage of ensuring early and dependable revenue for the government. Royalties charged on the gross value of production, however, are insensitive to costs and, thus, to the underlying profitability of projects. If set at high rates, investors may perceive them as an implicit depletion policy as they are likely to increase the marginal cost of extraction and reduce the range of feasible projects. This does not seem to be an issue in Guyana, however, as existing PSAs appear to enjoy royalty rates well below of what is observed internationally.

The report said that in jurisdictions that imposed ad-valorem royalties, rates often vary between 8 and 20 percent. For example, Trinidad and Tobago’s royalty rates for oil and gas range from 10 to 12 percent; the United States has assigned a 16.6 percent royalty in its Outer Continental Shelf; Colombia’s royalties are set between 8 and 25 percent; Brazil at 10 percent; and in Peru rates range from 5 to 20 percent

Cost Recovery limit

The report said that PSAs here limit the value of production (after royalty) that can be used to recover costs. The mission says it understands that the cost recovery limit in the Stabroek PSA is fixed at 75 percent.

“When there is a cost recovery limit and the minimum government share is greater than zero, an implicit royalty is embedded in the scheme. For example, a 75 percent cost recovery limit combined with a fixed government share of profit oil of 50 percent guarantees that the government will always receive a minimum of 12.5 percent of the total production (that is, a share of 50 percent of the 25 percent profit petroleum remaining after cost recovery). More-over… since the Stabroek PSA also includes an ad-valorem explicit royalty of 2 percent, the combination of the explicit and implicit royalties yields an effective royalty rate of 14.25 percent (That is, 2% (royalty) plus 50% of the remaining 25% after the royalty, or 2% + (98% x 25% x 50%) = 14.25%), which is more in line with international practice. The implicit royalty concept of course only applies when the cost recovery limit is in effect. Once recoverable costs fall below the cost recovery limit, the amount of profit oil to be divided between the contractor and the government increases and so does the government share of profit oil”, the report said.

Interest expense

The treatment of interest expenses appears to be generous, the report said.

“The treatment of interest expense is important because excessive or abusive use of debt can have a detrimental impact on the amount of profit oil to be shared between the government and the contractor … The mission understands that in Guyana’s PSAs interest expenses, irrespective of the source of financing, are permitted to be recovered provided that such expenses are consistent with market rates. Moreover, interest payments are exempt from withholding taxes, providing yet another incentive for contractors to finance their costs with debt. Services provided by affiliated companies, on the other hand, are recoverable as long as they are based on actual costs (without profits). The charges for related party services should be no higher than the usual prices charged by the related company to third parties for comparable services under similar terms and conditions elsewhere, and must be fair and reasonable in the light of prevailing international oil industry practice and conditions”, the report said.

It added that it is common to have limitations on interest deductibility to reasonably shield the tax base. It said that some countries disallow interest expenses or limit the amount of debt allowed for cost recovery purposes through caps on debt to equity ratios or “earning stripping rules”. Other countries may require that interest may be deductible only on borrowing to fund development costs or a maximum percentage of such costs. Uganda’s model PSA, it said, allows interest on loans (from any source) to finance development operations only up to 50 percent of the total financing requirement. Interest on loans to finance exploration is not allowed.

“Such a restriction could be supplemented with regulations or guidance defining the financing requirement as the cumulative negative cash flow, including tax paid but excluding other disallowed costs”, the report said. The mission added that it understands that it is common here to exempt petroleum and mining companies from withholding tax on interest payments. Therefore, restricting the amount of debt for cost recovery purposes or disallowing interest expense altogether in PSAs may be appropriate.

Profit petroleum

The FAD report pointed out that the government share of profit oil is fixed at 50 percent in the case of the Stabroek agreement and not uncommon in modern PSAs. It asserted that the main disadvantage of this type of mechanism is that it does not enable an increasing share of profit oil/gas to the government linked to the profitability of projects.

“Most PSAs around the world usually have a formula in which the government share increases as a function of production, a combination of production and prices, or an economic variable such as the ratio of cumulative revenue to cumulative costs, or the project’s internal rate of return. Moreover, in many countries, the top tier government share of profit oil could be as high as 80 or 90 percent”, the report asserted.

It said that two common production sharing mechanisms are the daily rate of production (DROP) and the R-Factor.

“In the former, the government share of profit oil/gas increases with the daily rate of production from the field or contract, often with several tiers. Although the DROP is an imperfect proxy for project profitability, many countries have adopted this system. Under the R-Factor scheme, on the other hand, the government’s profit share increases with the ratio of contractor’s cumulative revenues to contractor’s cumulative costs (hence the term the ‘R-Factor’). The R-Factor is commonly seen as an improvement over DROP, although critics point out that it does not recognize the time value of money”, the report stated.

Ring-fencing

The FAD team pointed out that ring-fencing in a PSA framework can limit the allocation of income and expenditure for profit oil sharing and tax purposes. With such a ring fence, the scope to consolidate income and expenditure across multiple fields is circumscribed.

“In the PSA framework in Guyana, the sharing of profit oil between the contractors and the government is done on a field by field basis. In principle, this ensures that the government revenue from the contract area is calculated based on each field separately. However, this is undone by the PSA framework also allowing the contractor to allocate cost oil to any field within the contract area.

“While Guyana does not place any restriction on the deductibility of interest under the ITA (Income Tax Act), it does impose a withholding tax on interest payments of 20 percent subject to double taxation treaties. Profit oil sharing linked to the cumulative rate of return in contrast would take into account the time value of money, although it is inherently difficult to determine the appropriate rate of return”, the report said.

It cautioned that this asymmetrical treatment of profit and cost oil is likely to benefit contractors with a number of fields within their contract areas at the expense of delaying government revenue. For example, it said that a contractor with multiple fields can significantly lower the amount of profit oil to be shared from a producing field by assigning cost oil from various fields under development to the producing field. This could have “significant implications” in terms of delaying government revenue, particularly if a large, multi-field project is launched in phases.

“Given the size of the contract area thus far awarded in Guyana, there is merit in applying a tighter ring-fencing arrangement as part of the general PSA framework. An option could be to apply this at the level of individual fields, perhaps only allowing failed exploration expenditures to be deducted against producing fields”, the FAD report stated.

Taxation

The FAD report said that according to the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission’s published minimum terms, the contractor’s Corporate Income Tax (CIT) liability is paid out of the government share (also known as pay-on-behalf system). In other words, the government share of profit oil/gas includes CIT and, therefore, the contractor does not have to make separate CIT payments. Further, since the CIT is included in the government share of profit oil, this implies a ring-fence around the contract area for CIT purposes. This type of arrangement it said is also called post-tax production sharing, as the profit oil sharing includes CIT. It said that an advantage of this approach is that it facilitates a measure of fiscal stability for companies, while protecting the government from abusive CIT planning as companies do not gain from engaging in such activities.

“Although the effectiveness of the PSA in this respect does depend on the specific accounting rules for allowable deductions for cost. When this type of production sharing is used, usually the government share of profit oil/gas is higher than what the share would be if the contractor were separately liable for CIT. In the case of Guyana, this implies that the fixed 50 percent share is relatively low”, the FAD team stated.

Given that the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Agreement allows the Minister of Finance to exempt the holder of a PSA from most tax laws, it is unlikely that other taxes apply to the contractor.

It stated that subcontractors may also benefit from tax exemptions under the PSAs. It said that the 2012 model PSA provides for broad tax exemptions for subcontractors.

“For example, Article 15.10 states that withholding tax on payments made by the contractor to sub-contractors or affiliated companies do not apply during the exploration period. Moreover, Article 21 says that subcontractors engaged in petroleum operations are exempt from VAT and import duties on imports of equipment and supplies required for petroleum operations, except for excise tax on fuel imports at a rate of 10 percent. In addition to the forgone revenue, this introduces administrative complexities and risks of tax evasion. Finally, interest and dividend payments from affiliated companies’ or non-resident sub-contractors’ branch in Guyana to its foreign or head office or to affiliated companies are exempt from withholding taxes”, the report said.

Economic evaluation of Stabroek PSA and international comparisons

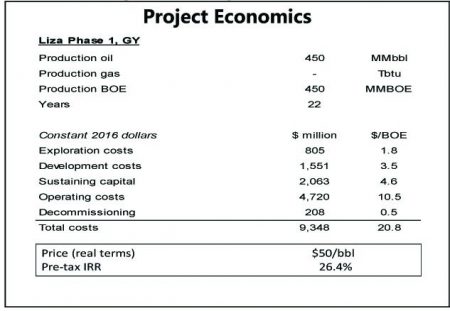

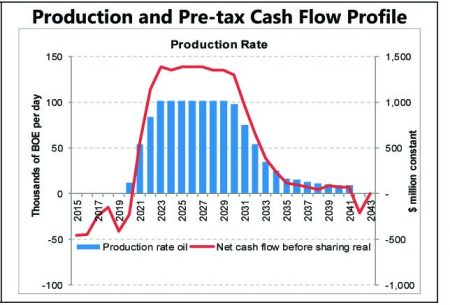

For the evaluation, the mission said it used the project economics of the Liza Phase 1 development. The project, located approximately 190 kilometers offshore in water depths of 1,500-1,900 meters, will be developed using a floating, production, storage and offloading (FPSO) vessel. According to ExxonMobil, the FPSO has a capacity to produce up to 100,000 barrels of oil per day (bopd), and store 1.6 million barrels. Total production is expected to be approximately 450 million barrels of oil over 22 years.

It said that simulations were done using FAD’s Fiscal Analysis of Resource Industries (FARI) methodology. The sample includes large producers from the region, such as Brazil and USA, medium and small oil producers such as Colombia, Peru and Trinidad and Tobago, and other mature producers such as Australia and Norway.

It said that the project requires an investment in exploration and development of approximately US$4.4 billion, and total per unit costs of around US$21 per barrel. With an assumed price of US$50 per barrel over the life of the field in 2016 dollars, the project provides a real pre-tax internal rate of return of about 26 percent.

The revenue generating capacity of the fiscal regime, it said, is evaluated by estimating the Average Effective Tax Rate (AETR) or “government take”. The AETR is computed as the ratio of government revenue to the project’s pre-tax net cash flows over the life of the project using a discount rate.

“The Stabroek PSA has the lowest AETR of all the fiscal regimes evaluated. This result confirms that the terms offered in the agreement are generous to the investor, but were probably required to attract investment at a time in which little was known about the geological prospects of the country. Moreover, some of the countries with the highest AETRs in the sample, such as Norway and Trinidad and Tobago, are mature and well-established producers that have had the opportunity to fine tune their fiscal regimes overtime”, the evaluation said.

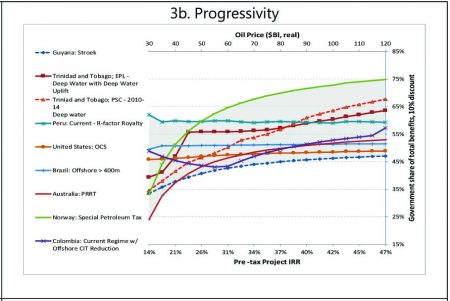

The FAD team contended that the degree of progressivity of the fiscal regime is also vital for governments and investors.

“A more progressive regime increases automatically the government’s share of revenue when the investment is highly profitable, while giving some relief to investors for projects with low rates of return. The progressivity of the fiscal regime is evaluated by estimating the government share of total benefits over a range of different prices and corresponding pretax internal rate of return for the project. The FAD team said that while the Stabroek PSA is progressive, the overall government “share of total benefits, even at very high levels of profitability, is very low compared to the other countries in the sample”.

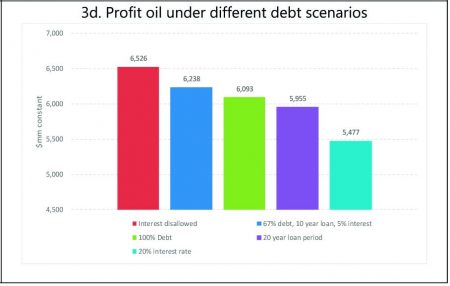

The mission also evaluated the effect of different debt scenarios on the government’s share of profit oil. If there is no restriction on the use of debt for cost recovery purposes, excessive or abusive use of debt can significantly cut the government’s share of the profit oil. It looked at various scenarios: (i) no recoverability of interest expense; (ii) 2 to 1 debt-to-equity ratio, 5 percent interest rate and 10 year loan term (the base case); (iii) 100 percent debt financing, and the same interest rate and loan term as in the base case; (iv) 20 year loan term, and the same interest rate and debt-to-equity ratio as in the base case; and (v) 20 percent interest rate, and same loan term and debt-to-equity ratio as in the base case.

“The difference in the government’s share of profit oil between the scenario in which interest is disallowed and the one with high interest rate is over (US)$1 billion in forgone government revenue over the life of the project (in undiscounted real terms)”,the FAD team said.

International Comparisons and Treatment of Interest Expense Analysis

It presented a series of recommendations to the government:

Make PSAs public within a framework providing a level playing field for disclosure that protects commercially sensitive and proprietary data.

Close fiscal loopholes in existing PSAs, in consultation with existing contractors, that may be a source of base erosion and profit shifting activities.

Undertake a policy review of fiscal terms contained in existing PSAs to ensure that these are implemented appropriately, and assess areas of improvement for future investment.

Design a new generally applicable fiscal regime for upstream petroleum projects that increases the government take and limits the scope for individual negotiations.

Ensure that royalties are paid directly by PSA holders and not included in the pay-on-behalf system.

Introduce a revised production sharing mechanism for new PSAs that provides the government with a higher share of profit oil as the profitability of projects’ increases.

Publish a model PSA that includes the minimum fiscal terms accepted by the government for future contracts.

For the general PSA framework going forward, apply a tighter ring-fencing arrangement at the field level, including for the allocation of cost oil.

Consider conducting competitive bidding rounds for future allocation of petroleum rights.

Continue to develop petroleum tax policy and fiscal modeling capacity at the Ministries of Finance and Natural Resources.