Senior Counsel Ralph Ramkarran and the Guyana Bar Association both concur with President of the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) Sir Dennis Byron’s position that recourse can be sought to the court over the failure to appoint a substantive Chancellor of the Judiciary and Chief Justice for over a decade.

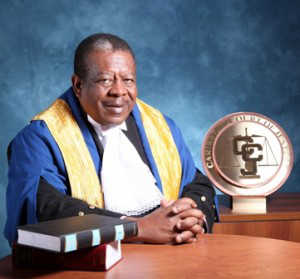

Delivering the keynote address at the 37th Annual Bar Dinner last month, the CCJ head had said it was disappointing that no substantive Chancellor has been appointed after Justice Desiree Bernard’s departure and noted that having both offices being led by judges acting in respective capacities is “a most unfortunate state of affairs.”

Justice Byron added that “The delay in complying with section 127(1) of the Constitution has long reached a level of justiciability and the most appropriate authority for resolving this situation is the court system”.

In an invited comment, Ramkarran made it clear that substantive appointments should at least have been made during that period in which retired judges Carl Singh and Ian Chang both served in acting positions after the last substantive Chancellor Justice Bernard joined the bench of the CCJ in 2005.

Justices Singh and Chang acted as Chancellor and Chief Justice, respectively, up until their retirement. Singh retired in February, this year, while Chang retired a year earlier. Following a meeting between President David Granger and Opposition Leader Bharrat Jagdeo in March, Justices Yonette Cummings-Edwards and Roxane George SC, were appointed as acting Chancellor and acting Chief Justice, respectively. The two leaders have not met further on substantive appointments.

Ramkarran has not taken particular issue with the delay in confirming the current office holders, while noting that unlike in the cases of Justices Singh and Chang, an unduly long time has not yet elapsed since their elevation.

He added that while the constitution does not stipulate a timeframe during which the substantive appointments are to be made, it surely does not envision an inordinately long period, such as decade or more.

He further noted that the president has not yet sought confirmation of Justices Cummings-Edwards and George from the Leader of the Opposition, so that the constitutional process is not yet in place for such considerations to be made.

Article 127 (1) of the Constitution provides, “the Chancellor and the Chief Justice shall each be appointed by the President, acting after obtaining the agreement of the leader of the opposition.”

Asked what steps can be taken once a certain period has elapsed without substantive appointments being made, Ramkarran said that legal proceedings can then be initiated, especially given the dynamics of local politics, where the two sides “almost never agree on anything.”

He clarified that “no one can say exactly when one can go to court” but added that any elector on the voters’ list can initiate proceedings. He added that even an acting Chancellor and/or Chief Justice can commence proceedings to challenge their acting positions.

When asked whether there may be gaps in the constitutional provision itself, Ramkarran said he knows of no gap and he suggested that the matter being taken before the court is a means of addressing any lack of agreement between the president and opposition leader.

‘Agreement shouldn’t be protracted’

Meanwhile, for his part, President of the GBA Kamal Ramkarran has said it is a very unfortunate situation that both Justices Cummings-Edwards and George, who are eminently qualified, have not been confirmed.

He added that it is unfair to ask the current acting Chancellor and Chief Justice “to do the work, and not have the job…They are essentially the Chancellor and Chief Justice,” he stressed, while noting that they are expected to give 100% of their services and not merely what may be considered an “acting” share thereof.

In an interview with this newspaper, he said that one month should be the longest persons are asked to serve in an acting capacity. When asked, he also noted that there are implications for security of tenure where persons are serving in acting capacities, while adding that they can be removed from those specific offices at any time.

He recalled that from 1966 to present, there has never been acting appointees for the two top legal posts for long as it has now been—12 years.

Like Senior Counsel Ramkarran, the GBA President said that legal proceedings can be initiated by any private citizen as a means of bringing attention to the issue and impressing upon the president and the leader of the opposition the need for substantive appointments. The Bar Association itself, he noted, may consider such action in the future.

Expressing his personal view, he said the “agreement” implied into Article 127(1) cannot be unreasonably withheld, nor should it be protracted for an unreasonable time. Added to that, he said that any objection to a nominee put forward, must be substantiated by good reasons in a reasonable time.

He, too, noted that no name has been put up by the president for the opposition leader’s agreement and as a result there is nothing to consider at the moment.

If for some reason the two sides cannot agree, he said, the court, in interpreting the constitutional provision, can give effect to the fact that the agreement “must be met within a reasonable time or there must be good reasons for not agreeing.”

In keeping with the spirit of the constitution, Kamal Ramkarran explain-ed that the aim is for agreement to be met after a name would have been put forward. “It could not mean that if there is no agreement, then there should be no appointments,” he noted.

In his speech, Sir Dennis had pointed out, that Article 127 (1) was a key subject of amendments in 2001.

Whereas under the previous 1980 Constitution, the Chancellor and Chief Justice could be made by the President after “consultation” with the minority leader, under the 2001 amendments, the actual agreement of the leader of the opposition is now required. Juxtaposing Article 127(1) with 127(2), Byron noted that, “the use of the word “shall,” in Article 127(1) imposes a mandatory obligation upon both the President and the Leader of the Opposition to come to an agreement on the persons to be appointed as Chancellor and Chief Justice.

Article 127(2), states, “if the office of Chancellor is vacant… then until a person has been appointed to and has assumed the functions of such office… the functions shall be performed by such other of the judges as shall be appointed by the President after meaningful consultation with the leader of the opposition.”

Sir Dennis reasoned that any appointment made pursuant to Article 127(2) is envisioned as a short-term appointment. He said this highlights a critical factor in the interpretation of Article 127 as a whole; that is, that Article 127(2) does not provide an alternative method of appointing the Chancellor and Chief Justice.

Article 127(1), he said, ascribes an obligation on the president and the leader of the opposition that is mandatory in nature and not discretionary. “Any failure in fulfilling this obligation must therefore be regarded as a breach of the Constitution,” he argued.

He advanced that despite the subjective component of reaching agreement, the constitution could not have intended the decade-long paralysis that has resulted from the failure to agree.

The judge surmised further that the reason the bar may have been lifted from “consultation” to “agreement” is because the appointments are important to “good governance and the welfare of citizens,” and he stressed that “failure to agree is not an acceptable option in the interpretation of that constitutional provision.”

Sir Dennis had questioned whether there exists an appropriate statutory or regulatory framework to establish agreement. He observed that if this is answered in the affirmative, that may be a basis for judicial intervention, but if answered in the negative, then now would be the opportune time to address any existing regulatory or statutory gaps adding that that this may also be a basis for judicial intervention.

Commenting directly on this, Kamal Ramkarran said he knows of no regulatory framework as to how agreement must be reached, apart from what the constitution provides. He, however, suggested that in the absence of such a framework, Parliament could enact a provision, amending how the process of agreement should be reached. This, he said, would have to be achieved by way of getting the support of a two-thirds majority in the House.

Sir Dennis bemoaned the inability of successive presidents and opposition leaders to agree on appointing a substantive Chancellor of the Judiciary, while warning that prolonged acting appointments pose a genuine “risk” to the promise to citizens of an independent and impartial judiciary.

Referencing Article 122A (1), the judge said, that substantive appointments contribute to an independent judiciary. That article provides, “All courts and all persons presiding over the courts shall exercise their functions independently of the control and direction of any person or authority; and shall be free and independent from political, executive and other form of discretion and control.”

This provision, Sir Dennis argued, effectively promises to every Guyanese, a judiciary that is completely independent in all aspects. “It cannot be said that this provision contemplates and/or condones in any way, prolonged acting services of the country’s number one and number two judicial officers,” he observed, while noting the genuine “risk” posed to the constitutional promise to every citizen of an independent and impartial judiciary.