Dear Editor,

Between 2002 and 2004 at least two public sector modernisation projects were undertaken by the Government of Guyana. The vision, which resulted from extensive discussion, was expressed as follows: “Within ten (10) years the Guyana Public Service will be a customer driven institution providing quality services for the economic stability and sustained development of Guyana through the 21st century. The Public Service will be small, comparatively well paid, efficient and effective, undertaking planning, supervisory and regulatory functions, facilitating and encouraging investment and the Private Sector; and operating within sustainable cost limits related to national economic performance.”

In the consultancy report of May 2002, the then Minister of Public Service was quoted amongst other things; as follows: “The advent of globalisation and its adverse effects on the global economy has made it indisputably necessary for governments to reform the public services. It must be recognised that a radically different way of doing things in the public services must be adopted. The new era will require a more flexible institution and the emphasis must be on strategic approaches to planning. The informed public sector therefore must be infused with new values, a higher sense of mission and purpose, and be totally conceptualised with a spirit of new professionalism. There must be a new management style of getting results.”

The study identified five cornerstones on which to modernise Guyana’s public sector management namely: i) strengthen policy development and coordination; ii) build performance management and evaluation structure; iii) establish a new human resources management infrastructure; iv) develop a management framework for arm’s length agencies, and strengthen their accountability.”

Unfortunately, the extant evidence is that nobody governing (or indeed opposing) seems to be aware of the recommended new dispensation. So that with all the talk about human resources management, Guyana, of all the Caricom countries (and indeed the rest of the world), can still boast of personnel officers (Chief, Principal, Senior, Officer II & I) ‒ a cumulative effrontery to the concept and practice of Human Resources Management.

Most of the incumbents therefore have but little sapiential, moral or organisational authority to develop any human resources.

In the meantime the Government of Guyana, over the past decade and more, has substantively restructured the definition and image of the ‘public servant’, while effectively emasculating the constitutional process by which the latter should be recruited, developed and promoted. The platform of ‘pensionable’ public service has shifted very fundamentally to that of a playing field for ‘contracted employees’ ‒ gratuitously (to use a bad pun) compensated at the rate of 22.5% of negotiable salary every six months, instead of a pension.

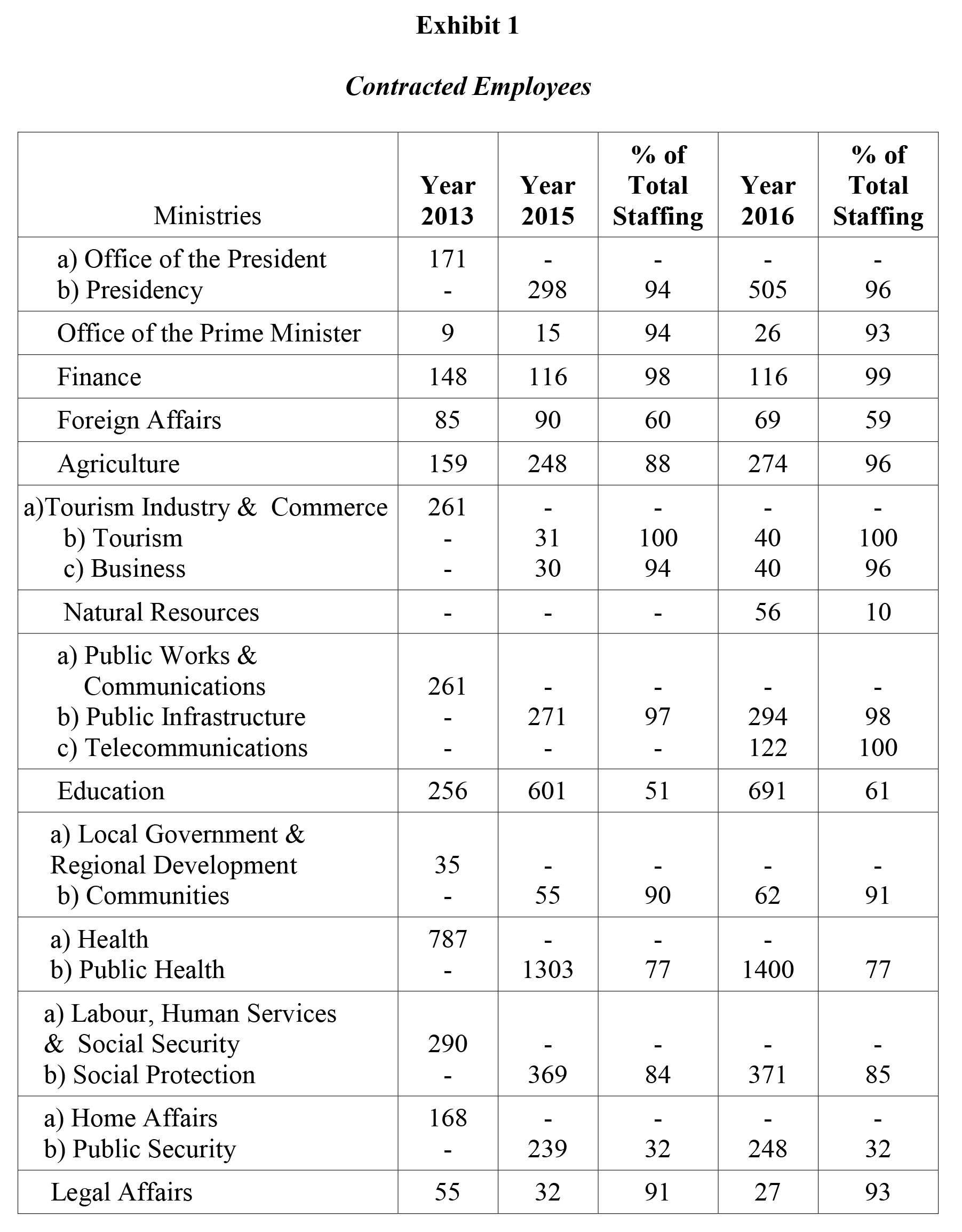

In 2017, despite the related recommendations of the Commissioner of Inquiry (CoI) into the ‘Public Service’, Budget Agencies autonomously continue to recruit their own (non-transferable) ‘contracted employees’. Apart from the exponential increase in the proportion of these ‘non-public’ servants, as depicted in the table at Exhibit 1, there are serious organisational and human resources implications, in respect of which there appears little evidence of being addressed. Amongst them are the following:

- i) The rationale for giving priority to recruitment on contract rather than on a pensionable employment basis, moreso without the formulation of a policy that ensures consistency of application

- ii) Having by-passed the constitutional authority of the Public Service Commission, there appears no credible alternative regulatory mechanism for monitoring the efficacy of the recruitment process

iii)The rapidity of expansion of this grouping gives cause for enquiring about the precision of job descriptions, if any; the consistency of specifications for even the same job in different agencies; the competency of interviewing panels (if in fact there are such functionaries who in any case may have also been contracted); how explicitly formalised the accountability relationships are; the existence of an effective performance evaluation process, particularly since the half-yearly gratuity payable to ‘contract employees’ is normally based on what is euphemistically described as ‘satisfactory performance’; despite the fact that the ‘contract’ arrangement facilitates easy separation on either side, it does, however, leave the more effective performer disposed to movement to greener markets, implying a certain vulnerability to the particular agency’s ability to sustain the level of needed delivery capacity; the potentially discomfiting issue of ‘contracted employee’ and traditional ‘public servant’ performing the same duties alongside each other, with the latter being disadvantageously compensated, given the element of bargaining embedded in the recruitment process of the former; the prevalence of an incentive system that involves duty free concessions is palpable.

Notwithstanding the above, the statistics at Exhibit 1 below, show that the situation has become so endemic as to be irretrievable, making a mockery of the views of the CoI into the public service about re-traditionalising longevity of employment in the public service, and the predictability of the latter’s sustainability.

The confusion inherent in this disaggregated employment process must obviously spill over into any system (if at all existing) for measuring performance for promotion. In such a vacuum therefore, it needs to be explained what coordinated systems and procedures exist to identify the strengths and weaknesses within, and across agencies which would inform the basis for structured remedial action, as well as other proactive training and developmental interventions.

In the latter regard, questions may reasonably be asked about the data used to identify specific target groups of under-performers; specific target groups of potentials for growth; the formulation of relevant programmes to address the above; the personnel with the relevant competencies to undertake the required analysis; in turn, the capacity to select the latter; and whether any of the above were considered as critically precedent to the establisment of a purported Staff college.

With great respect, there is no reason why any of the foregoing should not be the topic of conversation amongst ‘public servants’, and between the latter and their ‘contracted’ counterparts – on the not unreasonable presumption that some of both may be interested in careers.

All the above hold implications for productivity, institutional sustainability, as well as for the nature and timeliness of reporting relationships.

What is to be understood by the statistics is the flagrant indifference to the substantive recommendations made by the CoI into the public service, initiated by the very group of governance leaders.

The numbers above defy any organisational pretext, principle or practice, not to mention they show of a total lack of knowledge of any preceding plans to reform the public service, to make it not only ‘customer service’ oriented, but adequately professionalised to respond to global organisational change.

But one does not have a clue about the various levels of skills they bring onto the playing field, and therefore into which job grades those contracted employees are absorbed.

However much is the silence which appears to be ongoing, there is in fact a need for a comprehensive and articulate engagement with relevant expertise, with a view to constructing an intelligble (and intelligent) public service of the future.

Until then, how can the most earnest of citizens verify how much value is being obtained for the tax invested in the disaggregated environment which now obtains. The more imaginative may even wonder about the extent to which the concept of ‘subsidy’ may be applicable.

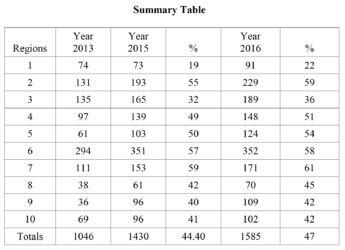

The situation in the Regions makes for more alarming reading. The summary table below reflects succintly the contract employment situation across the 10 Regions.

The more notable increases between 2013 and 2016 are seen in Region 2 – 75%; Region 4 – 53%; Region 5 – 103%; Region 6 – 20%; Region 8 – 84%; Region 10 – 48%.

Indicators are that there are more questions to be asked. It is arguable that as a follow-up to the aforementioned CoI, there should be a fastidiously detailed analysis of the deconstruction of the concept and fact of ‘public servant’. Does the GPSU wonder about the eligibility of contracted employees for their membership?

Yours faithfully,

EB John