For The D

which captured you nightly into

dead city, discovering through

streets steep with the sufferer’s beat;

Teach me to walk through jukeboxes

& shadow that broken music

whose irradiant stop is light;

guide through those mournfullest journeys

I back into harbour Spirit

in heavens remember me now

& show we a way in to praise I,

all seekers to-gather one heart;

and let we lock conscious when wrong

& Babylon rock back again:

in the evil season sustain

o heaviest spirit of sound.

Anthony McNeill

For Don Drummond

Dem say him born

with a caul,

a not-quite-opaque

white veil

through which he visioned

only he knew

At birth dem suppose

to bury it

under some special tree.

If we had known

we could have told them

it was to be,

the Angel Trombone Tree.

Taptadaptadaptadada. . .

Far far East

past Wareika

down by Bournmouth

by the sea,

the Angel Trombone

bell-mouthed sighs

and notes like petals rise

covering all a we.

Not enough notes

to blow back the caul

that descend regularly

and cover this world vision

hiding him from we.

[. . .]

Lorna Goodison

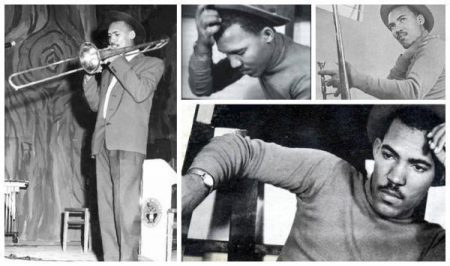

These poems are more than mere tributes. They pay homage to an immortal – the great Jamaican musician, innovator and folk hero Don Drummond.

Drummond was one of the Caribbean’s most popular and revered musicians – a trombonist who created forms and was particularly influential in popular music during the 1960s and seventies. He was a genius, but his extraordinary talent carried a price: he was also a tragic figure.

Such was his impact, his art, popularity and importance to the development of ska, rock steady and reggae, and he commanded such a place in the national consciousness of Jamaica, that he inspired the literature. Several poems were written dedicated to him, some of them very famous pieces by leading poets in Jamaican and West Indian literature. Two are printed above – “For The D” by Anthony McNeill and the first half of “For Don Drummond” by Lorna Goodison.

Missing from this is the prince of all poems dedicated to, and about Drummond – the best known, highest acclaimed and most celebrated – “Valley Prince (for Don D)” by Mervyn Morris. But that one is so well known and oft quoted that attention is here drawn to some of the others. What is of marked importance is that these poems belong to a great movement that introduced a new swing to West Indian literature after 1970, when the popular music for which Drummond was revered, formally merged with the written literature and two great traditions influenced each other to bring about a progressive leap forward in West Indian poetry.

The main new form at the core of this development was ‘officially’ announced with the publication of Savacou 3 and 4 in 1970. New forms, genres, movements in literature do not happen overnight and it is usually impossible to put an exact date to them. But it has happened more than once in history when a very important change or era or form of literature was identified with a single publication. Good examples are the beginning of the romantic movement in poetry with the publication in 1798 of Lyrical Ballads by Wordsworth and Coleridge, and the acknowledged establishment of modern(ist) poetry with the publication of The Wasteland by T S Eliot in 1922.

Savacou was a literary journal coming out of the University of the West Indies Mona Campus in Jamaica starting in the late 1960s. The double issue, Volumes 3 and 4 in 1970, was mainly dedicated to a collection of new poetry – very revolutionary in form, structure and language, testing yardsticks for the measurement of value and excellence because of the unprecedented ways in which they used language and verse. There were three main threads running through them – their overriding subject which was social, political and cultural protest; their use of language which was straight or heavily influenced by creole (Jamaican patois); and their oral quality with an especial ring influenced by reggae music and its rhythms.This was the birth of what became known as “dub poetry”, an art that was in the making and developing since 1968, but which was linked with the popular musical evolutions since long before – perhaps 1958. But it did not settle itself into the written literature until around 1968.

Dub poetry then was brought to official mainstream notice when several ‘poems’ of a controversial and to some disturbing and questionable nature, were published in Savacou. Again, such new literature is very often in existence long before it is recognised, formally codified and given a name by critics. This was the case, for example, with ‘theatre of the absurd,’ which was much in evidence in the plays of Anton Chekhov in the first decade of the twentieth century, but not articulated until more than 40 years later by critic Martin Esslin and the work of playwright Samuel Beckett.

The creole poetry of Louise Bennett was in existence since 1938 but it was not until the recognition given to it by Mervyn Morris (a pioneering critical article in 1963) and Rex Nettleford (editing of the first collection of Bennett poems in 1966) that official mainstream literature accepted it. (And if you want to know, published poems in Jamaican creole/patois, emerged since Claude McKay in 1911 and Una Marson in 1936.) Morris, however, was a catalyst to wider recognition of not only Bennett but creole verse and orality in the scribal poetry.

The critic who most effectively codified and gave formal recognition to the arrival of dub poetry and the quality of verse coming out of the DJ performances in reggae which climbed over into the written verse was Gordon Rohlehr in 1971. He argued a case for the legitimacy of the new verse in articulating the “Problems of Assessment”.

Then in 1979, Rohlehr, along with Morris and Stewart Brown published Voiceprint, another crucial stage in the acceptance, recognition and establishment of not only work out of the oral tradition, oral poetry, but scribal poems with or influenced by the orality. It is this work that was continued by Kwame Dawes when he edited Wheel and Come Again: An Anthology of Reggae Poetry published by Peepal Tree Press in 1998.

Included in these are the poems about Drummond, often referred to by such titles as “The D”, “Don D” or “The Don”. He was a legend for his role in the music’s evolution from ska. He played in the famous star spangled band, the Skatalites, and by himself as a studio musician providing the backing for several recordings that saw ska transform into rock steady in the middle 1960s.

His influence was also noted as rock steady evolved into reggae by the middle to late 1960s. There were also his own solo creations such as “Far East”, “Occupation”, “Eastern Standard Time” and “The Reburial of Marcus Garvey”. But he was described as “Jamaica’s most talented and most troubled trombonist.” The poets McNeill, Goodison and Morris refer to his tragic circumstances, the mixture of his genius and his insanity.

These poems are excellent examples of mainstream scribal verses by established poets that capture the depth of the integration of the popular music into the verse. There is a mixture of subject matter and style and the poets’ concern for art, humanity and tragedy. These are deep-rooted factors in the poetry that emerged out of West Indian poetry’s excursions into popular music, dub, reggae, creole language and orality in an important brand of literature.