A 40-minute drive from Georgetown along the East Coast Demerara road would bring you to Two Friends, a busy little village, precisely 29.5 kilometers from the city.

Two Friends is home to more than 400 people including quite a number of porknockers, gold miners and construction workers.

It is the rainy season, but the day I visited the sun was peeking through gray clouds and not being sure whether they would have much of it, as things didn’t look too promising, villagers were quitebusy trying to make the most of it.

One villager requested that I speak to Philip Adams from Ann’s Grove who had some information on both villages. According to the 75-year-old, the contiguous villages, Ann’s Grove and Two Friends, used to be one estate called Two Friends. It was jointly owned by two friends who were Dutch and was in both their names. However, Adams said, his foreparents being illiterate had a difficult time pronouncing the Dutch and instead of using their names, called them ‘the two friends,’ hence the village’s name today.

According to Adams, just after slavery was abolished, the estate was sold to a British man named John Croal, who later encountered problems with the ex-slaves and decided to sell. On April 28, 1849, 75 ex-slaves pooled their resources and bought the western part of the estate for $10,000. The next week, on May 5, 1849, another 75 ex-slaves purchased the eastern section, paying $7,000. In recognition of Croal’s sister, Ann, the eastern part was renamed Ann’s Grove, while the western portion retained the name Two Friends.

This year marked 168 years since the ex-slaves of Two Friends purchased their village.

Back out on the road, some men who were just finishing mixing cement at a house pointed me to the lady of the house, Eutil Walters, who was born in Two Friends in 1947. “Life was good,” she recalled. “We worked very hard making cassava bread and cassava starch.” To get the cassava starch, she explained, the juice had to be boiled. When it was finished, it would be sprinkled on clothes when ironing to keep them from rumpling for a longer time. She clearly remembered her parents paying $3.50 for a drum of cassava. When it arrived home, she and her siblings sat on the ground and cleaned the cassava, after which they after took the cassava to the factory where they grated it. They also made cassareep from the cassava juice. That was during the 60s and by the 1970s the factory closed.

“We used to walk and sell in the village,” she recalled. “We used to go to other villages also like Plaisance, Bel Air and Campbellville; we went till to Corentyne, Crabwood Creek, Sixty-Three, Seventy-Nine and Union. We used to go up with the train to Rosignol, take a steamer over, sleep at the Reno Guest House and then the next day we walk and sell.”

In 1964, an East Indian resident of Two Friends was killed one night—this was during the riot—and the following day the British soldiers had the village on “lock down,” she said; no one was allowed to leave their home. Around this time, a man she called “Mc Doom” had his home burnt down and her brother was fingered as one of the arsonists. However, Walters said, her brother worked in Georgetown and on the day in question he was at work, adding that he would never have done something like that. Though he pleaded his innocence, he still faced two years’ jail time.

In her earlier years, Walters attended Ann’s Grove Methodist School. She also found herself in different Girl Guides’ groups. “We used to learn to sew and cook; we did hiking and walked from Ann’s Grove to Buxton one time,” she recalled.

In those days, she said, the people living in Two Friends did strictly farming. Today, many persons have turned to gold mining, porknocking and construction as their means of income. The village, she noted, has always been one of self-help.

Currently, the Guyana Power and Light has an ongoing project where it is installing new posts and will soon be rerunning cables.

She said that the youth today are different in that they don’t stay close to home like the people of her generation, but go out there and find themselves work. However, she feels they seem to lack discipline and respect and that bringing back the Guyana National Service will help a great deal in this area.

Further along the street, two men were building a stairway. One was William Wilson, who shared that he’s the grandson of the Canterburys, one of the first families in Two Friends. His grandmother, Princess had eight children including a set of twins, one being his mother. She later married his father, Ovid Wilson, who at that time was a pupil teacher at Ann’s Grove Roman Catholic School. He later became the head teacher of Ann’s Grove Methodist School.

Wilson said his family later left Two Friends to live at different locations in Essequibo where his father was sent to teach. The family returned to the village when he was eight.

Pointing to the house that was being renovated, he said it was once a coconut factory run by his uncle, who after leaving in the 1950s for the interior, returned in the 1960s and set up the factory. Some eight persons were employed and an average of 40 persons benefited.

Wilson attended North Georgetown Secondary then the Government Technical Institute, where he secured a diploma in Building and Civil Engineering, before attaining a degree in the same discipline at the University of Guyana. He followed in his father’s footsteps, teaching for four years (1974-1978) at Ann’s Grove Methodist School, before moving to GuySuCo as a superintendent of works (1978-1984). From 1985-1992, he worked with the Mahaica Mahaicony Abary/Agriculture Development Authority and later did a consultancy with SIMAP, Caribbean Engineering Company and A&E Consultancy. He currently has his own engineering company, Wilson Design and Construction Services.

“The people in the community are closely bonded, they live like family,” Wilson said. “Most of this generation is into building. This may be the only village with this much carpenters and joiners.”

Life is comfortable, he said, he just wishes the roads were fixed. However, he noted that road work was being done in Ann’s Grove and it seems like they’re working their way to his street.

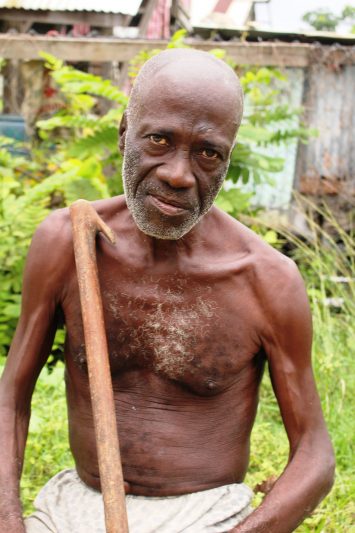

Sixty-five-year-old Kenneth ‘Kish’ Toney sat on a log outside his house chatting with the children who passed by. Near him, a staff he uses as a support was braced against the log.

He recalled boyhood days when he attended Ann’s Grove Roman Catholic School and on many days, instead of taking the road home, he would go through a section of the backdam they called ‘Guava Bush’ where he climbed the trees and made a feast of the guavas with his friends.

During his early years, too, he followed his grandfather into the backdam and looked on as he worked. “I use to keep his company,” he said. His grandfather, he recalled, planted suckers, cassava and cash crops.

Years later, in his twenties, he toiled in the same backdam to provide for himself and his family.

“Here is lovely,” he said. “In this village, everybody free-handed. I don’t have to buy greens or mango or coconut.”

However he added, “I want the people of Two Friends to be more cooperative. Nah becaw meh bruk-up, meh can still give lil advice.”

I then went in search of Herbert Sertimer, the last one still alive of the 12 persons who had formed a co-op that led to a housing scheme opening on the northern side of the village.

According to Kenny Soso, the area was once a pasture and was used for horse racing. It was also used for the purpose of burning bricks. Later it was turned into a rice field, then a housing scheme. Soso did not know more and directed me to Sertimer’s residence, but as it turned out, the 80-year-old was very ill and could not be disturbed.