Often, the question is asked: Is chess an art, science or sport? The literature which surrounds the nature of chess likens it to an art. Fiction is abundant with chess players. From James Bond to the X-Men films, from the pens of Nabakov’s The Luzhin Defense and Cozens’ The King-Hunt, it’s all there.

Those who say chess is a science make the point very clear when they refer to symbols such as 0-0 (castling) or Nxc6 (functional notation). The standard way of recording chess notation is referred to as algebraic. One writer, Matthew Seidel, said it well when he wrote, “It certainly seems that chess has the same sharp crystalline beauty of mathematical proofs.”

Finally, chess is primarily regarded as a sport. It has its own certified biennial Olympiad. A successful and charismatic chess player pays attention to order and logic. He is trained like that. The game is won with dexterity and finesse, not with crude violence.

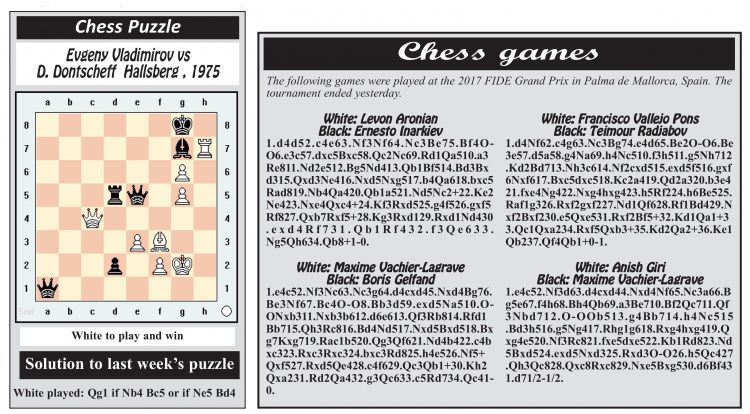

The Armenian chess grandmaster Levon Aronian is leading the charge for the 2017 Grand Prix at Palma de Mallorca in Spain. The Grand Prix represents a vital tournament because it qualifies the final two participants for the Candidates’ playoff in March 2018. Eight participants will play in the Candidates, and six have already been chosen. The winner and runner-up of the Grand Prix series will complete the list of eight. Additionally, the winner of the Candidates would go on to challenge Norway’s Magnus Carlsen for the world chess championship title.

Aronian has already gained his place in the Candidates and does not need the Grand Prix to qualify. The contenders, therefore, based on points amassed from their three previous Grand Prix tournaments, are Shakhriyar Mamedyarov, Azerbaijan, (340 points) and Alexander Grischuk, Russia (336 points). In the current tournament, Maxime Vachier-Lagrave of France (211 points) and Teimour Radjabov of Azerbaijan (241 points) would be attempting to overtake Mamedyarov and Grischuk since they are the front runners and have completed their three-round tally. The maximum number of points for each Grand Prix is 170. Radjabov’s severe loss to Evgeny Tomashevsky, however, will certainly hinder his chances of going forward.

Meanwhile, the Kasparov Chess Foundation (KCF) celebrated 15 years of global chess outreach earlier this month in New York. At a reception to mark the occasion, Kasparov, the 13th world champion, played a 10-board simultaneous exhibition.

The KCF has programmes in the US, Europe, South East Asia, Africa and the Pacific.