As indicated last week, today’s column is designed principally to pronounce on Decision Rule 4. Rule 4 focuses on the strategic direction for the best use of Guyana’s oil wealth, given its prevailing development predicament. In this regard, readers should recall that the previous column had summarily specified Guyana’s solemn medium to long-term commitments, at both the global and regional levels, for the sustainable utilization of renewable energy as the centrepiece of its aspirational development goals. These goals include, but are not limited to: 1) the global sustainable development goals (SDGs), 2015-2030; 2) Caricom’s adaptation of the SDGs and other global/regional goals (for example, Small Island Developing States, SIDS) as consolidated in the Caricom Sustainable Energy Roadmap and Strategy (C-SERMS); and 3) ultimately, the national goal of a ‘Green State’.

Natural resources review

Even the most cursory review of Guyana’s history, geography, economy, and resource endowment would certainly reveal that, next to its diverse peoples, its greatest resource endowment undoubtedly lies in its abundant natural resources. For that reason, I have been reviewing Guyana’s resource endowment in my weekly series of columns on the extractive industries. This series started almost two years ago (on December 27, 2015), in commemoration of Guyana’s 50th Independence Anniversary Year (2016). Above all else, the review has pointed to the pressing need for Guyana to develop dynamic and sustainable linkages between its ongoing extractive sector industries (spearheaded by the recent natural gas and oil finds) and the development goals of structural transformation of the economy along with the promotion of equitable sustained growth in real GDP per person.

As this review has revealed, there is a fundamental contradiction between the pursuit of an oil dependent economic strategy and the development of the Green State. This contradiction forms the basis for both Decision Rules 2 and 3, which respectively, have 1) rejected a state-owned oil refinery, and 2) declared a strategic economic option for natural gas development as the replacement downstream petroleum value-added investment.

Decision Rule 4 follows on the two previous decisions. Basically, it recommends as a solution to this contradiction (and other circumstances addressed below) the deliberate prioritizing of Guyana’s oil benefits for investment in the renewable energy sector. The deliberate aim here would be not only to satisfy the domestic market, but for Guyana to become a leading exporter of renewable energy in regional, hemispheric, and global markets.

The remainder of today’s column and next week’s following, will seek to support Decision Rule 4. And, also, to advance the further proposition that for Guyana, nothing less than a dedicated Ministry of Renewable Energy can fulfil this objective.

Reflections on context

There is undeniably widespread acknowledgement that Guyana possesses, “a wide array of opportunities … within the renewable energy sector” Go-Invest (2017). These opportunities include hydropower (estimates range from 7 to 10 thousand MW in at least 60 sites); solar energy (seven hours of sunshine per day, at an average of 5.1 kilowatts per square metre); bagasse (already supplying about 8 per cent of national energy); wood, charcoal, rice husk, wood waste, other biomass (over 80 per cent of the land areas is forested or woodlands); wind; and tidal energy. The problem is that we need an inventorization and clear scientific fix on each of these potentials.

It should be recalled, the information which was supplied last week shows that over the past three decades renewable energy growth has exceeded global energy growth, thereby leading to greater renewable energy intensity of global GDP. Furthermore, over the same three decades, renewable energy supply while accounting originally for 9.4 per cent of global energy, today this ratio has reached 22.4 per cent.

Contrastingly, we find Guyana has imported 5.5 million barrels of petroleum products in 2016, when compared to 4.1 million barrels in 2010. This explosive performance is the opposite of the global trend. It therefore, supports my recommendation for renewable energy investment in Guyana as a national priority. These data also specifically reject the present circumstance, in which the electricity sector is 92 per cent dependent on imported ‘dirty’ fossil fuels.

Why a ministry?

Decision Rule 4 recommends the establishment of a dedicated Ministry of Renewable Energy. This institutional recommendation is deliberate. And, while several considerations favour this recommendation, three are pivotal. First, a government ministry constitutes a specific sector of public administration. It is headed by a minister who holds a portfolio for it in the Cabinet. This circumstance assures that a ministry enjoys continuous, direct, and immediate representation at the highest executive level of the state. An agency or such other public body falls below a ministry. Second, given this stature, a ministry is capable of effective competition within the state, so as to ensure its mission can be achieved. A ministry becomes, in effect, the nodal point for all renewable energy matters.

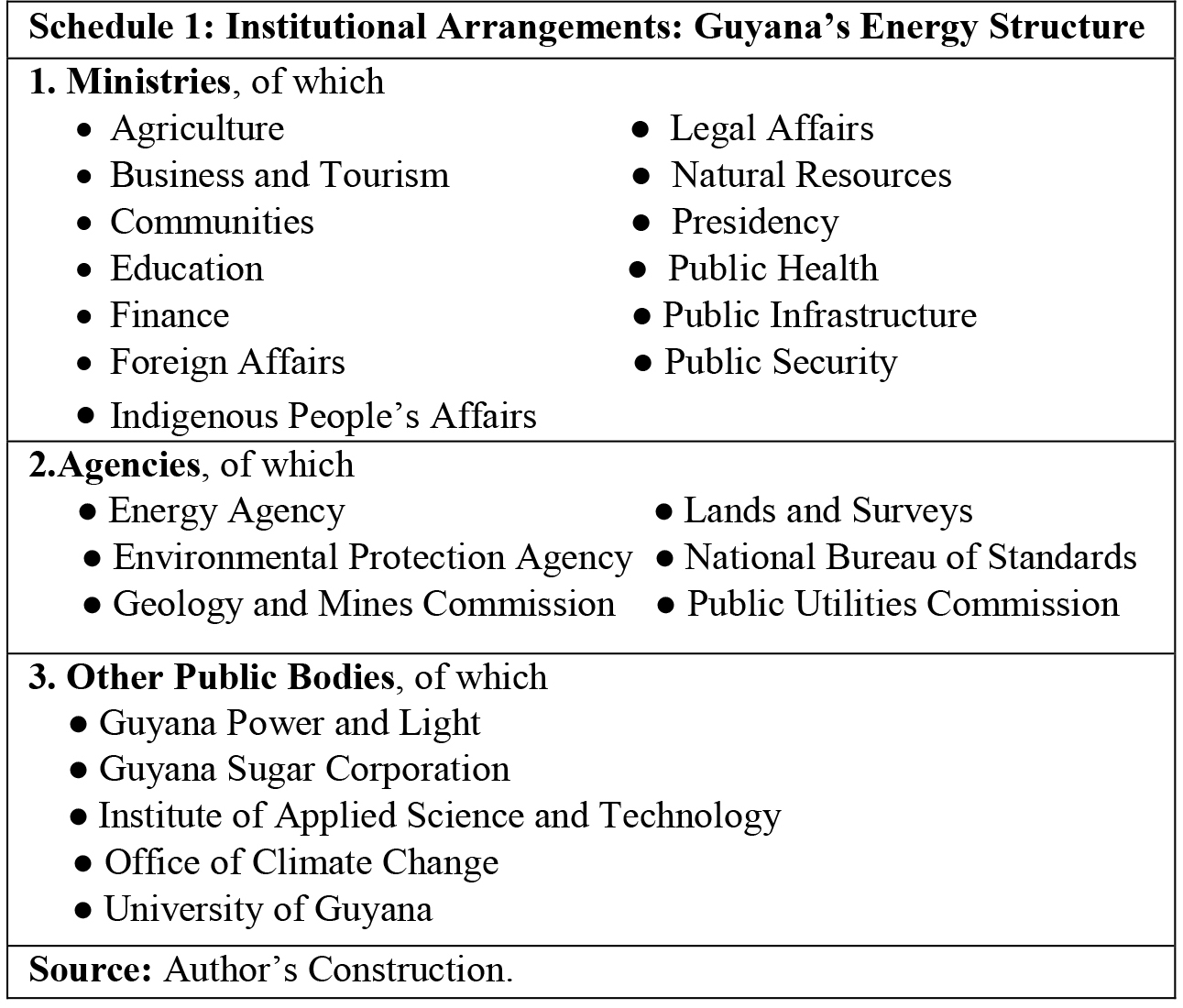

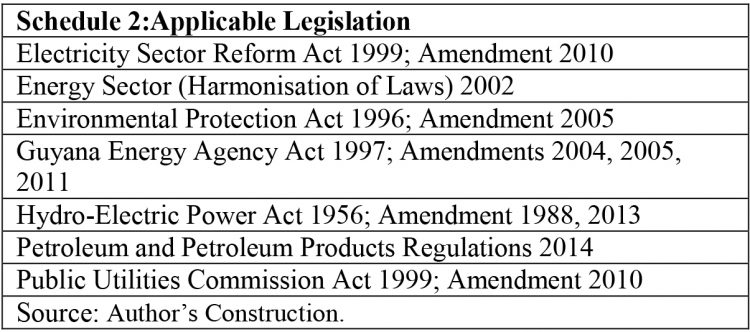

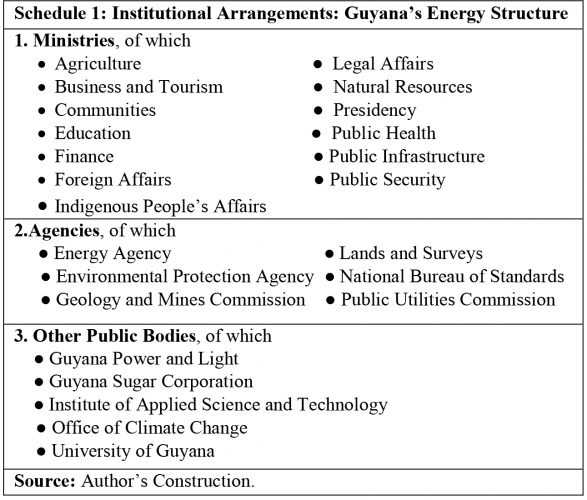

Third, Guyana’s existing legal and administrative superstructure governing the renewable energy sector is exceedingly complex and complicated. Consider the two main dimensions of this superstructure. First, at a rough count there are at least thirteen ministries with a varying, but substantial, say in the performance outcomes of the renewable energy sub-sectors. Additionally, there are six government agencies, as well as five other public bodies, which significantly impact on renewable energy operations.

Schedule 1 reveals this range and complexity.

Next week I will wrap up this discussion, with added elaboration on the case for a dedicated Ministry of Renewable Energy.