Bans A Killin

So yuh a de man me hear bout!

Ah yuh dem seh dah teck

Whole heap a English oat seh dat

yuh gwine kill dialec!

Meck me get it straight, mas Charlie,

For me no quite understand –

Yuh gwine kill all English dialec

Or jus Jamaica one?

Ef yuh dah equal up wid English

Language, den wha meck

Yuh gwine go feel inferior when

It come to dialec?

Ef yuh cyaan sing ‘Linstead Market’

An ‘Water come a me yeye’

Yuh wi haffi tap sing ‘Auld Lang Syne’

An ‘Comin through de rye’.

Dah language weh yuh proud a,

Weh yuh honour an respec –

Po Mas Charlie, yuh no know se

Dat it spring from dialec!

Dat dem start fi try tun language

From de fourteen century –

Five hundred years gawn an dem got

More dialec dan we!

Yuh wi haffi kill de Lancashire,

De Yorkshire, de Cockney,

De broad Scotch and de Irish brogue

Before yuh start kill me!

Yuh wi haffi get de Oxford Book

A English Verse, an tear

Out Chaucer, Burns, Lady Grizelle

An plenty a Shakespeare!

When yuh done kill ‘wit’ an ‘humour’,

When yuh kill ‘variety’,

Yuh wi haffi fine a way fi kill

Originality!

An mine how yuh dah read dem English

Book deh pon yuh shelf,

For ef yuh drop a ‘h’ yuh mighta

Haffi kill yuhself!

Louise Bennett

At this time in Guyana the issue of national language, of the status, acceptance and official recognition of the Creole language (Creolese or GCE in Guyana) is alive and current. There have been letters and comments in the national newspapers from skeptics on one side and professional experts on the other, about the language situation and the language issue. At the same time, academics at the University of Guyana have been driving the issues of language policy, language rights and the importance of Creolese (mother language of the majority of the population) as a national language.

It is a dialogue that has engaged the whole Caribbean for some 40 years. Public exchanges like the one recently taking place in Guyana have flared up in the press and other public fora from time to time, while linguists at the University of the West Indies and the University of Guyana have been working continuously in research, documentation, education and the issues of language teaching and approaches to Standard English. They have been working to enlighten the public and remove wrong perceptions while trying to influence official recognition of Creole as a national language.

At the same time the use of Creole languages in West Indian literature has made great and creative strides. It is going through the same struggle for recognition, acceptance by the academy and admission into the mainstream literature. But one can say that that struggle has been won where literature – poetry, fiction and drama are concerned. The national literature is fortified, enriched and given identity by Creole, while the knowledge and recognition of the spoken language remain on the battlefield.

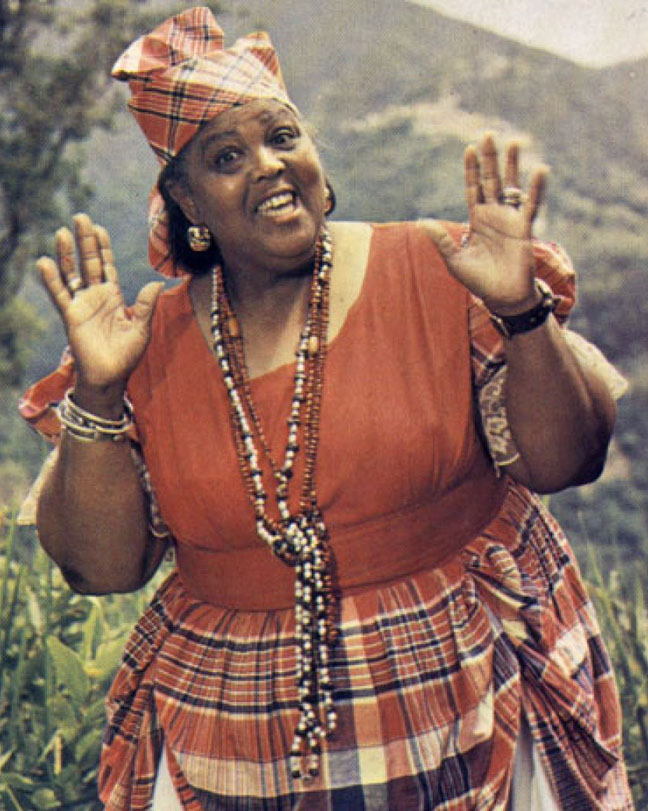

One writer who has been on the front-line of this struggle and who has done much to advance it is Jamaican poet Louise Bennett. She has done this as a writer, a performer and a positive activist. She has demonstrated remarkable accurate knowledge about language. This has been demonstrated in her work – her consistence, insistence and policy in using Jamaican Patois (Creole or JC) as the medium for performance, writing and instruction. She did a great deal of work among children and in teaching children.

One remarkable thing about all of this is the way Bennett does this advocacy through art – how her poems are a masterclass in teaching about the creole language. She entertains while imparting valuable facts, observations and criticisms about language which are integrated into a number of poems. Foremost among them are poems like “Bans A Killin” (see above) and “No Lickle Twang”.

The latter is a subtler, ironic poem spoken from the point of view of the persona – a mother berating her son for his “bad” language. He has just returned home after spending some time in the USA and she is disappointed that he does not speak with an American accent and has not changed from who he was to adopt the superficial, flashy accessories and appearance of prosperity. The poem is ironic because the mother is expressing the view of many Jamaicans – what she sees as bad is commendable and what she regards as good is regressive imitation.

“Bans A Killin” is the poet’s response to a large-scale rejection of Jamaica Patois, and creole languages generally coming from educated circles. Here her response shows a persona – a Creole speaker, who is more educated about language than the critics of dialect. Even the word dialect is misunderstood. It is commonly used as a synonym for creole and is reserved to name the creole variety of the language. But persons who do so are ignorant of the fact that Standard English – the Queen’s English or BBC English – the recognised British Standard (SE) is a dialect. It is the most prestigious dialect, the dialect of power, officialdom and influence; but there are several other dialects of the English language in England itself, many of them regional. As the poem points out, even the SE evolved from dialects spoken in Britain over an extended period.

The poem also speaks to the use of dialects in the most prestigious examples from the hallowed volumes of English literature, including those spoken by the unprivileged classes. It emphasizes the way the English of Chaucer was an emerging standard dialect while even the English of Shakespeare was still emerging as the modern Standard English but was still a dialect that was not even yet standardised. In addition to all that, the poem is clever for its use of wit and humour.

Dr Louise Bennett Coverley, OM, OJ, MBE, (September 7, 1919 – July 26, 2006) was a Jamaican poet, folklorist, actress, story-teller, comedienne, radio and TV commentator and performer. She was part of the comedy team “Lou and Ranny” with Ranny Williams and acted in the annual Jamaica Pantomime. According to The Guardian, “more than any other single writer” she “brought local language into the foreground of West Indian life”. Bennett was “critical of self-contempt” and said “when I was a child, nearly everything about us was bad, yuh know; they would tell yuh say yuh have bad hair . . . and that the language yuh talk was bad. And I know that a lot of people I knew were not bad at all – they were nice people and they talked this language.”

She was not the first to write poetry in Creole, but she was the most successful in reproducing the language and perfecting its rhythms in the verse. Claude McKay published poems in Patois in 1912 and Una Marson did the same including rejection of the “bad hair” concept in 1936. VS Reid attempted to narrate a whole novel in a variety of the Creole in New Day (1947).

Bennett began to publish her poems in The Gleaner newspaper in the early 1940s. Her first important collection was Jamaica Labrish (1966) edited and annotated by Rex Nettleford. Another was Selected Poems (1982) edited by Mervyn Morris.

Morris played a leading role in influencing Bennett’s admission into the academy with his famous essay “On Reading Louise Bennett Seriously” (1963), while Nettleford also played a part. A revolution of Creole verse in West Indian literature followed.