Cheddi Jagan returned from studies in the United States to a British Guiana in 1943 that was a cauldron of poverty. The report of the Moyne Commission, which investigated poverty in the region in the 1930s concluded that “for the labouring population, mere subsistence was increasingly problematic.” The report was so explosive that it was not published until 1945. It weighed heavily in subsequent developments. In 1946 Cheddi Jagan, Janet Jagan, Jocelyn Hubbard and Ashton Chase, the latter two of whom were active trade unionists, formed the Political Affairs Committee (PAC). In 1947 Cheddi Jagan fought and won a seat in the Legislative Council.

The cauldron of poverty was being stirred by decades of intensified industrial unrest, prompted by the new found strength of organised labour. The British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU) was the first to be registered in the British Empire in 1922. The Man Power Citizens Association (MPCA) was registered in 1937 and represented sugar workers. The Transport Workers Union (TWU) was established in 1938 and superseded the BGLU as the largest and most militant in the city. In 1947 bauxite workers went on strike. In 1948 the successful Teare Strike led by the TWU, stopped the trains and boats and closed down the country for two weeks – unprecedented in a colony. In 1949 the Enmore strike of sugar workers took place during which five sugar workers, who became known as the Enmore Martyrs, were shot and killed. This heightened labour activity was also a feature in the Caribbean region and was prompted by a decline in sugar prices on the world market which further exacerbated poverty.

In the wider world, the Second World War had ended with the Soviet Union gaining tremendous credibility with its defeat of Nazism, the British colonial stranglehold weakened with the independence of India and the rise of the United States as the leading world power, which was not sympathetic to colonialism. There were anti-colonial upsurges brewing in Africa and Asia and growing nationalist sentiment in many countries against foreign exploitation. All of these internal, regional and extra-regional factors influenced the formation of the PPP and its policies.

The composition of the PPP in 1950 showed a surprisingly mature political outlook by the then 33-year-old Cheddi Jagan. The PPP’s leadership was comprised of a broad cross section, ethnically diverse, combination of leftists, non-leftists, professionals, businesspeople, workers, trade unionists, youth, women and other groups, spanning the entire spectrum of the social composition of British Guianese society, with its Chairman being Forbes Burnham, a Guyana scholar and newly qualified lawyer. This national unity created by the early PPP and its overwhelming success at the 1953 elections, followed by its devastating division of 1955 and the ethnic divisiveness it generated in political expression and organisation, tapped into a national yearning for political unity across the ethnic divide, which persists to this day and remains unsatisfied.

The suspension of the constitution in 1953, one of the most traumatic events in Guyanese history, was not unlike the actions of British colonialism and American intervention in many parts of the world against nationalist leaders on the ground that the leaders or movements were ‘communist.’ This issue has been interrogated at length and in depth over the years. Jagan himself repeatedly offered the examples of the overthrow of Mohamed Mossadegh of Iran in 1953 and Jacobo Arbenz of Guatemala in 1954 by the CIA as intervention against nationalist leaders. Professor Colin Palmer in Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power: British Guiana’s Struggle for Independence (2010) convincingly demonstrates that the policies and postures adopted by the PPP in 1953 were reformist in character and scope, “tone and emphasis.” He said that although “stridently nationalist … the notion that the Guianese leaders were Russian puppets was profoundly misguided and constituted a gross misunderstanding of their nationalist aspirations.”

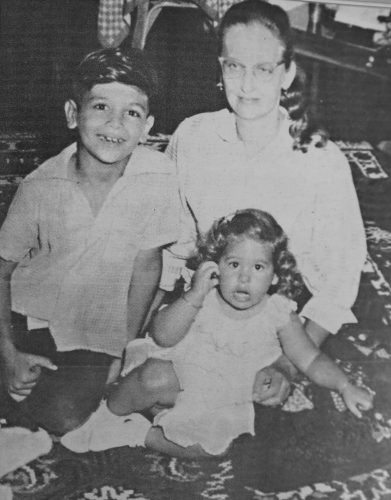

Palmer also pointed out that the Jagans were different kind of politicians. He said that while elitist politicians worried about the estate providing meals and sleeping accommodation when they went into the sugar estates to campaign, Jagan “together with his wife, had spent years going into these same areas eating, sleeping, and talking with the people, and it was this that had won him the affection of the people.” He said that they possessed that “rare but indefinable quality to obtain and sustain the abiding trust of the people in whose name they spoke … The Jagans had kept faith with their admirers, a quality that meant the efforts by the colonial regime to discredit them failed because the wellspring of their support was deep and suffused by a passionate, religiouslike fervour.” That “wellspring” of support was to continue for another fifty years.

The elections of 1957, in which the PPP was supported mainly by Indo Guyanese due to the split of the PPP in 1955, led by Burnham, Latchmansingh and others, and encouraged by the British, enabled the PPP to form the government. The PPP won also the elections of 1961 and the governments between 1957 and 1964 demonstrated the kind of policies that Cheddi Jagan was interested in – not ‘communist’ by any means. For the first time in Guyana’s history politics were put to the service of the people. Policies were established to vastly extend education, health, improve housing, expand agricultural and industrial production and expand infrastructural development. The record is there to see for anyone who cares to look. But what probably is most remembered is the Kaldor Budget of 1962 and the disturbances, including ethnic violence, which occurred in 1962 and continued under various pretexts in 1963 and 1964. The role of the British and American governments, their intelligence agencies and their local allies, have been fully exposed. It should be noted that throughout most of this period, Jagan sought a coalition government with the Peoples’ National Congress (PNC), a policy in different language and forms that he supported for the rest of his political career.

After the results of the 1964 elections, prematurely called by the British government, under the system of proportional representation imposed by the British to remove Jagan from office, notwithstanding the promise to grant independence to Guyana after the 1961 elections, Jagan argued that as the political party obtaining the largest plurality, the PPP ought to be called upon to form the government. This, of course, would have given him the opportunity to negotiate a coalition with the PNC. The British Governor, Sir Richard Luyt, would have none of it and called on the PNC, which obtained fewer votes than the PPP, to form the government. Of course, he knew what the long planned outcome would have been – a PNC-UF coalition government.

Perhaps Jagan’s greatest hour was the 28 years that he spent in the wilderness due to manipulated electoral practices. After the betrayal of the West, and in search of allies, he went from progressive nationalist to communist, in the years when the socialist and, more importantly, the Third World and the national liberation movement allied to the socialist world, were at their strongest. While his stature grew exponentially because of his advocacy for liberation and the end of exploitation and poverty against war and oppression, his steadfastness and commitment to principle and to the disadvantaged, were admired.

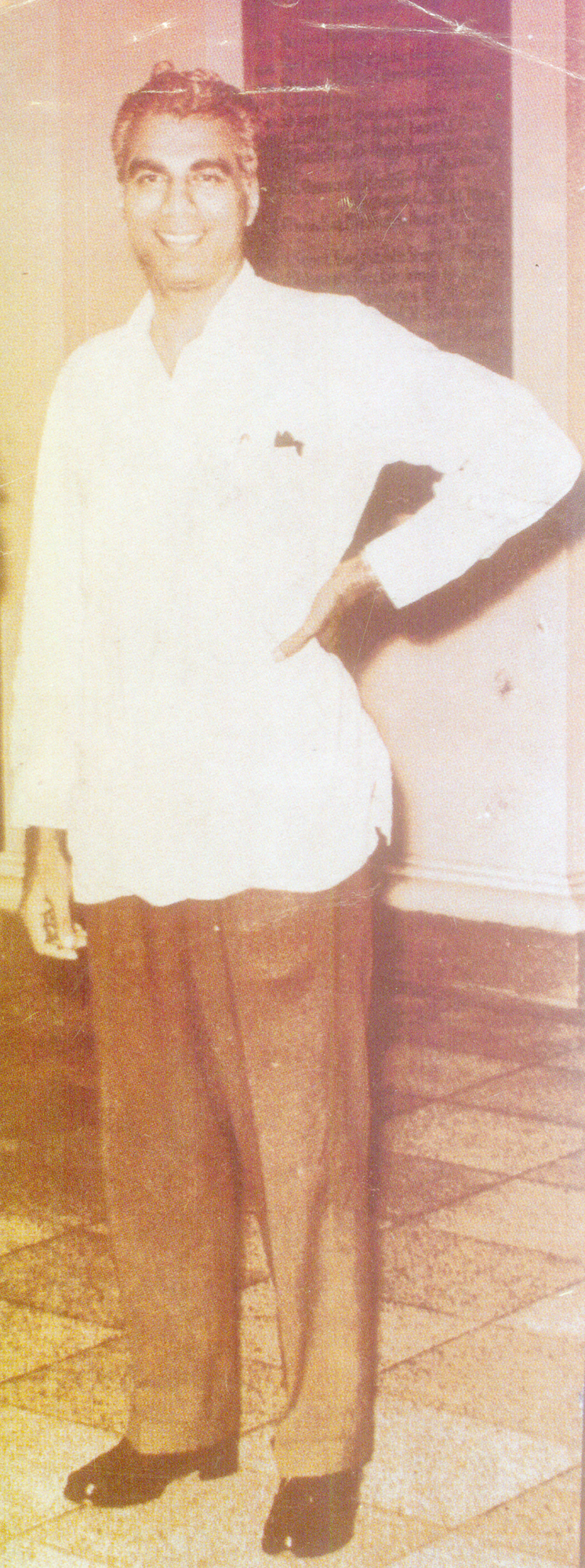

During this period he showed no bitterness, displayed humility, lived simply and shrugged off all the insults and attacks that were heaped upon him. He was never given to flights of oratory, or the quoting of Latin aphorisms to farmers or workers at public meetings. He frequently stopped at street corners on his way home from work in the afternoons when he saw a group of persons to engage them with his chart, which he kept in the trunk of his car, to demonstrate how profits are extracted from poor countries by multinationals or how poverty could be reduced by eliminating waste and expenditure on arms.

The criticisms against Jagan were not few. From his alleged communism in 1953, the signing of the Duncan Sandys letter in 1964, his alliance with the socialist world, exploiting Indian ethnic sentiments, to being naïve, he was under a constant barrage, not least from the PNC. During the PNC’s leftward shift, starting from the late 1970s, he came under increasing pressure from leading socialist countries to make accommodations with the PNC. He lost some stalwart comrades, and almost lost others, as a result of this pressure. But he maintained his posture that only the restoration of democracy could stabilize the political climate and ensure genuine progress in Guyana. He saw the restoration of democracy and the implementation of shared governance or a winner does not take all system as the two foundation elements, the twin pillars, for progress in Guyana.

Although Burnham rejected a coalition government in the 1960s, opportunities were missed between 1957 and 1961 and 1992 and 1997 to promote winner does not take all. Triumphalism may have played a role but in the latter period, the deep hostility of Desmond Hoyte precluded any approach to the PNC. But Jagan never wavered in his view. Were he here today, I have no doubt that he would agree that the establishment of a system where the two major parties share in the executive governance of Guyana, is unfinished business and needs to be ungently addressed.

The Guyanese people, and more particularly supporters of the PPP, were astonished at the outpouring of national sentiment when Jagan passed in 1997. The vast majority of the many thousands who turned out to pay their respects, at State House, along the East Coast and in Berbice, may not have known the detailed facts about 1950 and of those early years, or even of the intricacies of shared governance. But they knew that he cared about them.