In our article of 23 April 2018, we discussed Guyana’s Budget Transparency Action Plan (BTAP) that the Government had developed in 2015. The Plan contains 14 action items, of which advancing of the accountability cycle is perhaps the most important item. Once this action is fully achieved, the Government will be able to fully discharge its stewardship and accountability within 12 months of the close of the fiscal year, compared with what currently prevails where it takes approximately four years for the cycle to be completed.

Another important item in the BTAP is procurement planning which was the subject of last week’s article. This requires budget agencies to prepare and publicise comprehensive procurement plans in support of their budgetary allocations. While acknowledging that some progress has been made on several items of the BTAP, advancing of the accountability cycle as well as having procurement plans in place need to be accelerated.

Since the 2013-2017 cycle has ended, it would be necessary for a new PFM Action Plan to be developed for the next five years, building on the achievements recorded in the last five years. The recently concluded 2018 International Monetary Fund Article IV Consultation indicated that the Government intends to have a new PEFA assessment – the third of its kind – conducted later in the year. This is a most welcome development.

Ministry of Finance’s Internal Audit

Internal audit is an integral part of the internal control system of an organisation that analyses the strengths and weaknesses of an organization’s internal control systems; evaluates governance arrangements in place; and assesses opportunities and threats to the organisation and risk management. By providing regular feedback in these areas, internal audit renders a valuable service to the organization in facilitating management review and action towards achievement of organizational goals.

Internal audit in Government is not only a matter good governance practice. It is a requirement of the law. Section 11 of the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act requires heads of budget agencies to maintain an effective internal audit capability within their agencies. In his report on the public accounts for the fiscal year ended 31 December 2003, the Auditor General commented that “the absence of internal audit departments in large ministries continued to militate against an effective system of internal control and have contributed significantly over the years to the deterioration in financial management at both the ministerial and central levels”. This comment was repeated verbatim in the Auditor General’s 2004 and 2005 reports, but subsequent reports shied away from any commentary on the functioning of internal audit systems in Government, or rather their absence.

A review of successive reports of the Auditor General reveals that many of the comments are in the nature of internal audit findings. This reinforces the need to have in place an organized system of internal audit throughout the operations of Government, thereby freeing up the Audit Office to undertake high level reviews, such as the conduct of performance audits. In fact, Section 24 of the Audit Act 2004 vests with the Auditor General the responsibility for conducting: (i) financial and compliance audits; and (ii) performance or value-for-money audits. In conducting the latter, the Auditor General is required to examine the extent to which a public entity is applying its resources and carrying out its activities economically, efficiently, and effectively and with due regard to ensuring effective internal management control. However, after more than 13 years since the passing of the Act, only four performance audits were conducted, one of which was a follow-up audit.

Prior to the development of the PFM Action, the Ministry of Finance had begun a process of establishing a centralized Internal Audit Unit to provide internal audit coverage at not only the Ministry of Finance but also at other Ministries, Departments and Regions. The Action Plan relating to the Ministry’s Internal Audit contains 16 action items, of which the following are the most relevant: recruitment of additional staff; training of staff in internal audit techniques at both the Ministry of Finance and at budget agencies; development and implementation of internal audit plans; and monitoring and follow-up on audit findings and recommendations.

This centralized approach to internal auditing in Government may not be appropriate to provide the desired level of coverage, especially for larger Ministries and Departments. In this regard, we refer to item 10 of the BTAP which requires the Ministries of Public Infrastructure, Education, Public Health, Communities, Agriculture, as well as Ministry of the Presidency to have in place organised systems of internal audit by December 2016. The Auditor General was to have reported on the effectiveness of the functioning of these internal audit units in his 2016 report to the National Assembly. However, it is not clear what progress has been made so far to have such a decentralized internal audit system in place. Regrettably also, the Auditor General’s report provided no guidance or commentary on such a fundamental governance and accountability matter.

Office of the Budget

Two key items in the PFM Action Plan relating to the Office of the Budget are: a revised coding structure for the Estimates of Revenue and Expenditure; and training on the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF). A review of the 2018 Estimates, however, indicates the coding structure remains the same as that of previous years, indicating that this action is yet to be achieved.

In our column of 11 December 2017, we had stated that annual budgets are prepared, not in isolation, but in the context of a strategic framework that outlines priorities of an organisation over the medium-term, usually three to five years and that a commonly used tool is the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF). An MTEF is an “annual, three year rolling expenditure planning. It sets out the medium-term expenditure priorities and hard budget constraints against which sector plans can be developed and refined. MTEF also contains outcome criteria for the purpose of performance monitoring. MTEF together with the Annual Budget Framework Paper provides the basis for annual budget planning”.

Prior to the MTEF’s implementation, many developing countries experienced a disconnect between policy making, planning, and budgeting. The MTEF has therefore become a central element of PFM programmes for developing countries. It consists of “a top-down resource envelope, a bottom-up estimation of the current and medium-term costs of existing policy and matches these costs with available resources”. By the end of 2008, two-thirds of all the countries have adopted MTEFs.

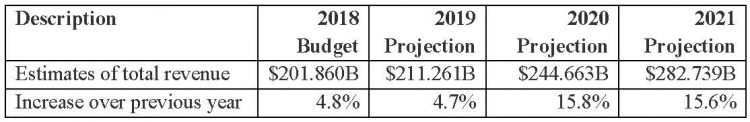

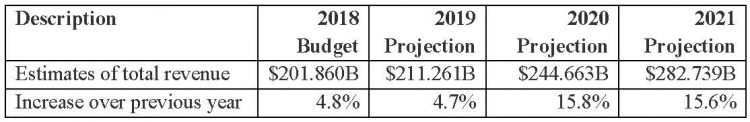

Guyana’s adoption of the MTEF can be traced back to 2010. An examination of subsequent years’ Estimates shows that, while indicative figures for both revenue and

With oil revenue expected to flow in 2020, it does not appear that this has been taken into account in the above projections in respect of rents and royalties as well as the Government’s share of profits from the extraction and sale of crude. The significant projected increase in revenue for 2020 and 2021 is attributable mainly to corporation tax, income tax, value-added tax and excise tax. In particular, the amount of rents and royalties is projected to remain substantially the same as that for 2018 at around G$4.7 billion.

While the Estimates do contain Programme Performance Statements, the indicators of achievement in terms of outputs, outcomes and impacts need to be quantified to facilitate independent ex post evaluation and to ensure good value for money is achieved.

Guyana is, however, not alone as regards the implementation of the MTEF, as several developing countries are faced with similar problems. We iterate our hope that for future budgets, there will be an outline of the Government’s medium-term policies and how they are linked to its MTEF. In this way, the estimates, including the indicative figures for the next three years, can be viewed in context.

To be continued