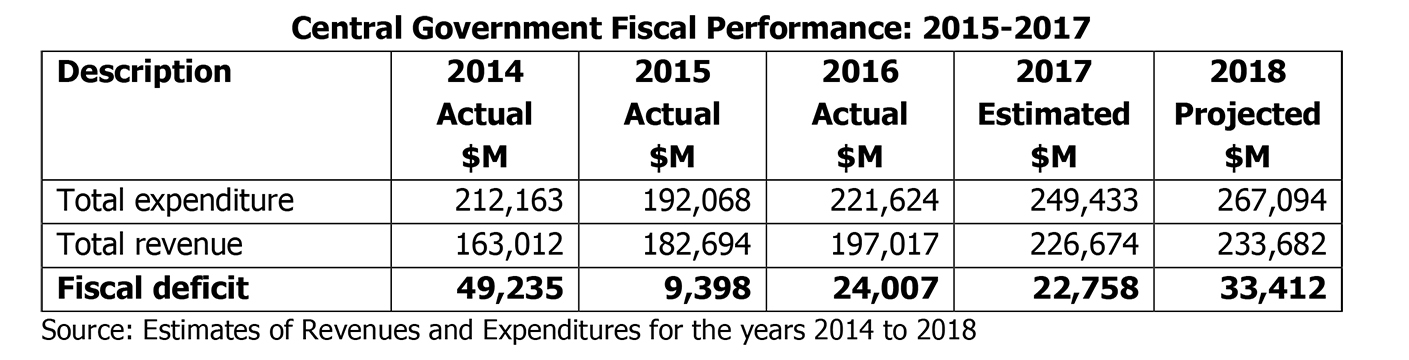

A particular area of concern relates to the fiscal deficit. Over the last 25 years and possibly longer, almost every year, public expenditures have outstripped revenue collections. The following table shows the recorded fiscal deficit for each of the last four years as well as projections for 2018:

It is evident that an urgent need exists to narrow the gap between revenues and expenditures so that in the longer-term a balanced budget can be achieved, thereby eliminating borrowings to finance the expenditures on Government programmes and activities. At the end of 2016, the overdraft on the Consolidated Fund was $132.876 billion. When the projected fiscal deficits for 2017 and 2018 are taken into account, the overdraft at the end of 2018 is estimated at $189.046 billion!

Today’s article is based on another policy document to be found on the Ministry of Finance’s website. We refer to the Privatisation Policy Framework Paper (PPFP) that was prepared following the change of Administration in 1992. During the period 1989-1992, a total of 15 State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) were either totally or partially privatised, including Guyana Telecommunications Corporation, Guyana Timbers Ltd, Demerara Woods Ltd, Livestock Development Co. Ltd, Guyana Fisheries Ltd, Guyana Rice Milling & Marketing Authority, and Guyana National Trading Corporation.

Historical Background

During the mid-1970s, Guyana’s economy began to deteriorate rapidly due mainly to the collapse of sugar prices in 1975 and the weakening demand for bauxite. Reduced export earnings led to a shortage of foreign exchange. As a result, Guyana began to experience difficulties in servicing its external debt which stood at 187% of total exports in 1980. By 1989, that figure rose to the astronomical figure of 668%. With the devaluation of the Guyana dollar in 1989, total debt exceeded 600% of GDP.

By the mid-1980s, Guyana was unable to meet its debt servicing obligations and ceased making payments to most bilateral and multilateral lenders. As a result, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) declared Guyana ineligible for access to further credit from the Fund. Guyana became the first member country to have been denied such access. The country was therefore technically bankrupt. Real gross domestic product declined by an average of 2.8% during the period 1980-1988; output in 1986 was only 68% of 1976 levels; and inflation averaged 20% resulting in a widening of the public sector deficit. More significantly, Guyana’s per capita income in 1991 was only US$290, one of the lowest in the Southern Hemisphere and the lowest in the Western Hemisphere. Correspondingly, the value of the Guyana dollar depreciated dramatically from G$2.55 = US$1 in 1975 to G$10 = US$1 in 1988, then G$122 = US$1 at the end of 1991.

Following the death of President Burnham in 1985, it was left to the Hoyte Administration to initiate efforts aimed at reversing the economic decline. In mid-1986, the Government entered into negotiations with the World Bank and the IMF for a rescue package to overhaul the economy and to free it up to market forces. The formulation of the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) was completed in 1988. This involved various austerity measures as well as the privatisation of loss-making SOEs in order to not only ease the financial burden on the Treasury but also to transfer them to the private sector. The latter was better placed to reverse the fortunes of these entities, thereby contributing to an improvement in the economic performance of the country.

Introduction to the Privatisation Paper

The PPFP was very critical of the pre-1992 Administration’s handling of the privatisation activities. It asserted that “[p]ublic opinion holds that transactions have been concluded too hastily, have failed to achieve optimal prices for state assets divested, did not consider participation of Guyanese in the process and did not secure preservation of national assets.” The Paper went on to state that Government’s interest in privatisation goes beyond budgetary concerns and that the aim is to increase efficiency and productivity of the SOEs involved through infusion of new investments, technology and efficient management. The PPFP further argued that sound privatisation policy is complementary to the Government’s desire to promote a vibrant private sector.

Statement of Policy

The overall strategy of privatisation activities is to liberalise the economy in order to create a more competitive and market-driven environment. Specific strategies include:

(a) Streamlining the public sector through comprehensive administrative reform aimed at making Government bureaucracy more responsive to development needs;

(b) Removing excessive bureaucratic interventions in the marketplace without sacrificing Government’s role as regulator; and

(c) Broadening the base of ownership and competition in the economy, including

support for small and medium business.

The scope of the programme includes commercially-oriented SOEs. Private sector participation would also be considered for SOEs that provide basic services to the extent that it would improve efficiency and provide better services to users.

Guidelines for Privatisation

The PPFP outlines the following procedures to be followed:

(a) Privatisation to be implemented in an open and transparent manner;

(b) Technical preparatory work, e.g. audit, valuation and legal opinion, to be conduct ed in advance;

(c) Advertisement as widely as possible for all SOEs considered for sale or othermodes of privatisation;

(d) Use of various privatisation options – outright sale; joint venture; public offer ing of shares; employee and management buyout; leasing; fragmentation; and

combination of any of the above options – depending on the option best suited for a specific SOE; and

(e) Employee participation to be encouraged, and measures put in place to address possible impact on workers to the concerned SOE.

Institutional Framework

The Public Corporations Secretariat and the National Industrial and Commercial Investments Limited (NICIL) are to be combined, and a Privatisation Unit established under the purview of the Cabinet to carry out privatisation transactions. The Unit would: (i) prepare for Cabinet broad guidelines on operating policies and procedures for implementation of the programme; (ii) identify priority entities for privatisation; (iii) develop action plans for implementation; (iii) conduct a public relations campaign; and (iv) help to build national consensus in support of the Government’s programme.

A Cabinet-level Privatisation Board is to be appointed with responsibility for ensuring that all procedures and safeguards that are established and are consistently followed in each privatisation operation. The Board would be an advisory body comprising five individuals, including the Ministers of Finance, Trade and Agriculture, and representation from the private sector, labour and consumer association.

Enterprise Selection and Prioritisation

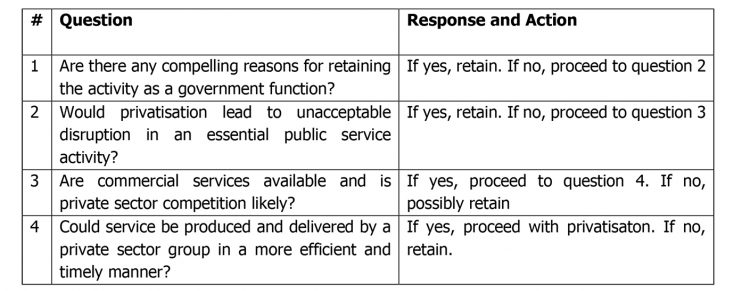

The selection of SOEs for privatisation is to be based on the decision tree approach advocated in a 1987 publication by the International Centre for Economic Growth entitled “Privatisation and Development”, taking into account the responses to the following four questions:

Those SOEs identified to remain with Government would be considered suitable for restructuring while those judged eligible for transfer to private sector will be referred to the Privatisation Unit for further review and recommendation. In the process of privatisation, an SOE may undergo a brief period of enterprise restructuring as may be required in order for transfer to be carried out on terms which are beneficial to both Government and private investors. This may also require the enactment of legal instruments to facilitate the process of transfer of interest, especially in Government entities with no share capital.

An assessment of eligible SOEs would be undertaken to determine the priority ranking of identified SOEs for transfer to private sector, taking into account (i) contribution to the National Treasury; (ii) contribution to the attainment of sectoral objectives; (iii) broad ownership; (iv) enterprise efficiency and productivity; (v) ease of effecting transfer; and (vi) business attractiveness to the private sector.

SOEs Identified for Privatisation

The PPFP identified 20 SOEs for privatisation, of which privatisation activities have been completed in respect of 14 SOEs. The remaining six are: Guyana Oil Co. Ltd, Hope Coconut Industries Ltd, Guyana National Printers Ltd, Guyana Sugar Corporation (GUYSUCO), Guyana Electricity Corporation (now Guyana Power and Light) and Linden Mining Enterprise. GUYSUCO is in the process of being restructured through the closure of four of the seven Estates and their preparation for privatisation.

Conclusion

Although the PPFP was prepared in 1993, it is still relevant and useful, considering the privatisation activities currently being undertaken in respect of GUYSUCO. However, given that most of the SOEs identified in the PPFP for privatisation have already been divested, it may be useful for the paper to be revised to reflect the policy of the present Administration and its priorities as regards privatisation. Perhaps, there are lessons to be learned from past privatisation activities which should inform the formulation of a new PPFP.