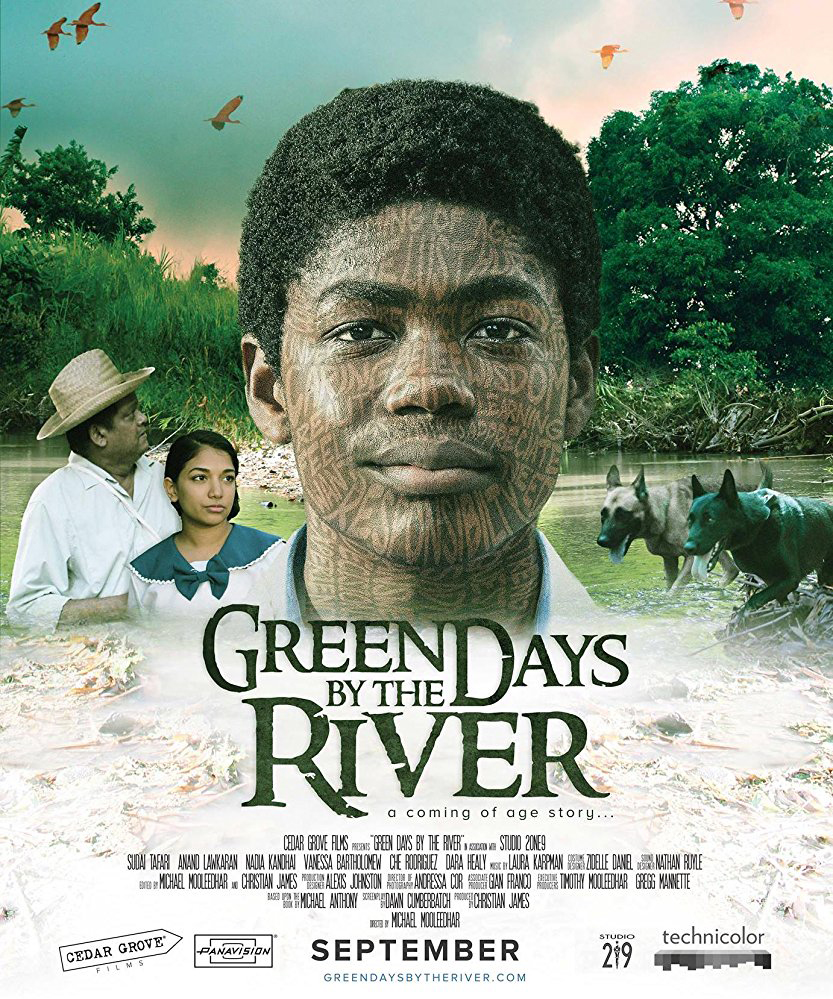

This is a very specific tale of a very specific boy living in a very specific time. The potentially universal aspects of the story (struggles with masculinity, teenage love, and teenage betrayal) are all specific because of the way it all depends on the specificity of its protagonist, Shellie Lammy. It’s why Anthony’s novel depends so much on the narrative structure of the tale told through its protagonist’s murky memories. The promise of a Trinidadian adaptation of this Trinidadian tale was good news, but I wondered how the idiosyncratic voice of the tale’s text would be or could be translated for film. Director Michael Mooleedhar’s film (written by Dawn Cumberbatch) nixes the obvious translation of Shell’s voice on the page to one of voice-over narration. At only 100 minutes, the film instead front-loads itself with montages to depict mid-20th century Mayaro as a place that becomes a crucible for Shellie.

Your mileage may vary, but the fact that his dual romantic relationships both seem too quick to be deep becomes a boon rather than a curse. Shell is too unformed to be certain of his feelings and the rapidity with which the film seems to thrust him into romance seems more an effective commentary on teenagers than the film. Mooleedhar’s camera is more confident in the scenes that are less dependent on dialogue. The film, in some extended wordy scenes, seems to stall when it should propel forward. Shellie’s relationship with the land-owner Gidharee, for all the talk of romance, is the most essential relationship of the story. The film depends on Mr Gidharee’s successful wooing of Shell as a potential son-in-law. Anand Lawkaran, who portrays the character, is clearly aware of the magnitude of his role and attacks it with gusto but the chemistry between him and Tafari is the film’s only real threat of liability. His Gidharee’s jocularity comes across as too deliberate to be natural, and too forced to be charming. Of course this reading, then, changes the course of the story in a way that hardens the tough themes later on in the film. Moreover, it hardly destroys the film, which emerges as an essential beacon in 21st century filmmaking in the region.

There is a scene midway through “Green Days by the River” where the narrative pauses for an extended musical break. Musical instruments and a mournful song seep through the narrative to present a montage of a day in the life of a cocoa worker in 1950s Trinidad. It’s the surest scene of the film visually, which becomes ironic for how little the narrative needs but conversely how much the film benefits from it. It’s an excellent rendering of the kind of filmmaker Mooleedhar can be. I’d like to see Mooleedhar tackle something in the vein of a “Tree of Life” or “English Patient,” where the terrain becomes the protagonist. And, it’s a great credit that his film never feels buckled by its source.

There’s a beautiful shot of Tafari’s face a few moments before the end of the film. His expression is one of simultaneous bafflement and worry. The shot is so evocative, so right, that I wished heartily that it would have been the final shot of the movie. The actual final shot of the film when it does come, a tableau of Shell looking towards the future flanked by two key characters, feels too literal and on the nose and seems to turn his narrative from a specific internal one into one that argues for something more universal. I’m not sure if that take works. The specificity of Shell’s story is where either version of the text works. But that last shot is almost superfluous when Tafari’s expressive face throughout is telling us all we need to know. To come of age as a poor boy in colonial Trinidadian is a time that’s marked by confusion and consistent bafflement. I’m intrigued to see what Mooleedhar does next but my real interest after “Green Days by the River” is the hope that Sudai Tafari’s talent can be harnessed to make a career on screen.

“Green Days by the River” is currently playing at Caribbean Cinemas