The climax of the newly-released “Mary Poppins Returns” features the main characters attempting to, inexplicably, turn back time. For the magically opaque Mary Poppins, the impossible has always been just another thing to achieve and the moment on its surface seems to hit home the idea of the film’s own unreality. The clock that must go backwards, though, works even better as an incredibly explicit metaphor for a film, a story, and a legacy that is particularly indebted to the past.

The original “Mary Poppins,” released to critical acclaim in 1964, was the crowning live-action achievement of Walt Disney’s lifetime. It was the heyday for film musicals and even then the Banks family seemed to yearn for a time gone by. Now, more than 50 years later, we return to the story. Mary Poppins must come to help the Banks children – now adults, but also the children of the adult Michael Banks. Their family is navigating an especially dark and dismal time during the great depression. And what better than the stray gust of a wind, and a magical nanny from their past to blow some much needed joy into their lives? “Mary Poppins Returns” does not just look backwards, it lives in the past. Admiral Boom, the retired naval officer who lives next door, launches his canon on the hour, every hour. Except, his booms are lagging five minutes behind the correct time. But Admiral Boom’s five minute-lag is observed with mild amusement and warmth rather than consternation. It’s not that Boom is wrong; it’s just that things are out of place. And recognising the value of things forgotten is central to appreciating why and how “Mary Poppins Returns” works, beyond just being a reiteration of its predecessor.

P. L. Travers’ original books were intended for children and as family entertainment “Mary Poppins Returns” follows a long line of fantasy films that exist in a weird middle ground between explicit fantasy and unavoidable reality. Mary Poppins will drift into the lives of this family, she will take them on magical flights of imaginations or fantasy or whatever and at the end of it things that were awry will be mended, even if just momentarily. Rob Marshall’s film follows the structure of its predecessor to a pointedly deferential focus. But the film is not displaying mere obsequious fealty. Its central thesis is, perhaps, over-familiar. Adults grow old instead of growing up and, in their way, lose awareness of the flights of fantasy that are essential for life. This year, alone, we’ve been treated to “Christopher Robin,” “Isle of Dogs” and even “Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse” suggesting this point.

The adults needing to regain elements of their childhood is key to the tale. For, as per normal, Mary’s role is to save the father more than the children. In the original, Mr Banks had lost the time for his children. Here, an older Michael Banks is even worse off. He’s a recent widower on the verge of losing his house, having an abandoned his artistic career (strangely, his artistic skill is rarely given much focus). It seems like only a miracle could fix the slump that his home-life is in. And, indeed, the things that occur in the film border on miraculous. If a character’s sly point that, the one thing about Mary Poppins is she never explains anything, feels too pointedly meta-textual, it’s meant to be. This is a world with a Hispanic leading man, and other persons-of-colour in key roles that are uncommented on. It’s a world with almost preternaturally focussed children, and fantastic trips of mind and body. It is, of course, fantasy. But, not the kind of fantasy that depends on turning its back on the world. Instead, it’s the kind of fantasy dependent on recognising the ways that the imagination provides an essential salve to the worst of the world.

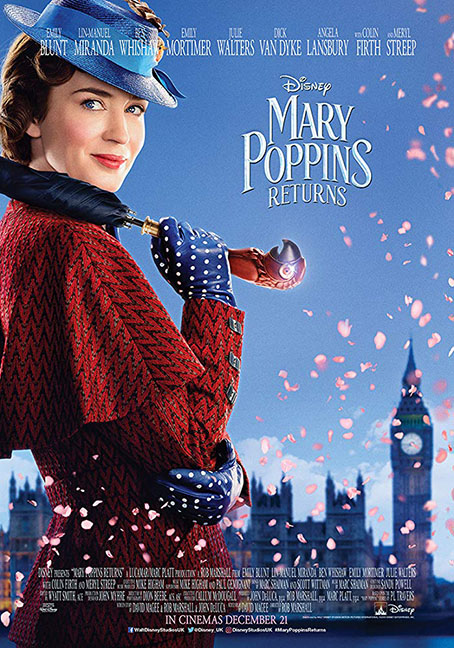

And, more than anything, it’s the woman at the centre that evokes this best. Emily Blunt’s Mary Poppins is decidedly her own. Blunt’s turn, like Julie Andrews in the original, is the film’s most effective weapon. And if the films themselves hew closely to each other, the difference in the two Marys is as good proof as any that different keys can open a single door. Blunt comes off as just slightly more knowing, and more arch, her voice – gorgeous as it is – is not Andrews’ angelic high soprano, but something more human but just as effective. There’s a peripheral growl she emits in a throwaway moment in a song that’s so randomly her own thing that her take on the character deflects comparison. Mary Poppins is a paradoxical woman, all tics and antics, but strangely real. Almost always supercilious and judgemental but warm and open. And even as her arrival promises joy, it also promises certain sadness.

And, so, the final number, “Nowhere to Go But Up,” a rousing ensemble piece featuring the cast joining in song, feels melancholic and joyful at once. Amidst the rousing melodies of the song, the lyrics suggest loss – but for us to go up, we must have gone. For, of course, Mary Poppins must leave the Banks children. She will forever be the eternal fixer whose job is expired when her wards don’t need her anymore. It’s a paradoxical relationship. For children must grow up and childhood flights of fantasies might very well be forgotten. But, then, even at the worst of times the idea that there’s a possibility of regeneration is a necessary flight of fantasy that keeps us all going. It’s a duality the film puts to good use.

“Mary Poppins Returns” is the most confident work Marshall has done as a director since he made his film debut directing Chicago, and it’s an impressive feat considering how it differs from the sly undertones of that musical film. “Mary Poppins Returns” is at its best when it gives way to the unbridled, and unselfconscious sincerity that a tale like this demands. The release feels apropos for the season. On a surface level, the flights of fantasy and happiness that the film is intent to give off align with the ostensible cheer of the Christmas season, but “Mary Poppins Returns” teems with a knowing depth of the limits of life, which turns it from a charming bauble to a surprisingly (but necessarily) robust appraisal of our time. “Nothing’s gone forever, only out of place,” Mary sings in the middle of the film. It’s an effective reflection of the film’s relationship with time. It’s looking back to the past, but not to eschew the present, but to recollect things forgotten that must be saved.

Mary Poppins Returns is playing at the Princess Movie Theaters and Caribbean Cinemas Guyana.