By Zoisa Fraser and Femi Harris

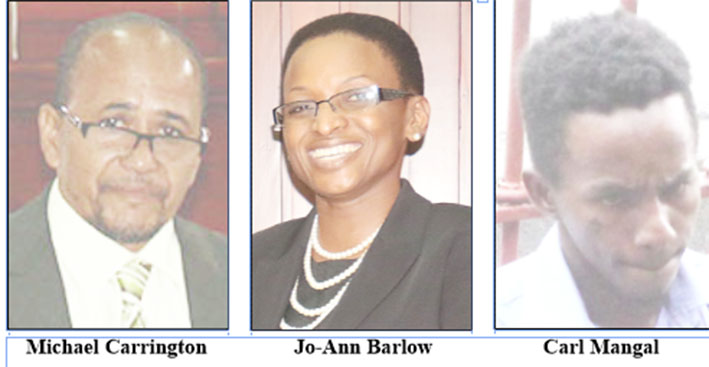

Despite an apparent divide between APNU and the AFC on reforming the sentencing for possession of small amounts of cannabis, government Member of Parliament Michael Carrington says that a reworked bill will come before the National Assembly by next month end.

A Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Control) (Amendment) Bill, intended to address the sentencing provisions of the law, was tabled by Carrington in December, 2015, and has been left to languish in legislative purgatory since that time.

However, Carrington told Sunday Stabroek that there should be movement by the end of next month.

“The party [AFC] has decided that we are gonna push it [the bill]. It should come up very soon by… next month… I will have at least the full support and the AFC and some members of the opposition may support it because it may go to a conscience vote,” he said in an interview last week.

Although Carrington, an AFC member, suggested that it was the APNU that delayed a debate of the bill after it was tabled, State Minister and APNU Chairman Joseph Harmon declined to respond to the assertion. He said that the issue is not about APNU and AFC, but about a member of the government’s side who has filed a bill which is “being dealt with by the government side. That’s the position.”

His comments came in wake of the widespread outrage that was triggered by the sentencing of Carl Mangal to three years in jail for the possession of 8.4 grammes of cannabis for trafficking.

The sentence has since been appealed.

The sentence prompted renewed calls for the reform of the sentences imposed, with many arguing that it was too harsh given the small quantity of the prohibited drug with which the father of three had been found.

Harmon has said the government believes the current laws do not allow magistrates the discretion to impose sentences below the mandatory minimum for possession of small amounts of marijuana, although a recent High Court judgment suggests otherwise.

Harmon stressed last Thursday that the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act, which was signed into law by the late President Desmond Hoyte in 1988, does not provide magistrates with discretion when they are dealing with amounts above a certain level. He further noted that the magistrates have to utilise what is outlined in the law and opined that if there is need for changes to the existing legislation, then that is the “responsibility of the legislative branch.”

Indeed, in handing down the three-year sentence to Mangal, Principal Magistrate Judy Latchman told his crying relatives that she was acting according to the law. However, a ruling by Justice Jo-Ann Barlow in March on the constitutionality of the mandatory minimum three-year sentence for ganja trafficking, had affirmed that magistrates do have the discretion to impose lighter sentences where special circumstances may warrant.

Judicial discretion

In a ruling on March 28th, 2018, Justice Barlow found that the lower courts do have discretion to go below the minimum sentence set by statute, given the particular circumstances of the case before it.

Referencing legislation and case law, the judge highlighted that courts can impose sentences, the length of which reflects the judge’s own assessment of the gravity of the conduct in the particular circumstance of the case before it.

Her ruling was based on an application brought by Vinnette James, Indrani Dayanarain and Karen Crawford, who all challenged the penal provisions of the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Control Act.

Among other things, the applicants sought to challenge the constitutionality of the imposition of the mandatory minimum sentences prescribed by the Act.

Their contention had been that the mandatory minimum sentencing provisions contained in the Acts were null, void and of no legal effect insofar as they rendered nugatory, the doctrine of separation of powers.

The applications by James, Dayanarain and Crawford were made on behalf of Dellon St Hill, Parsram Sancharra and Khalil Mustafa respectively, who had all been convicted and sentenced under the Act.

Their respective attorneys had argued that the legislature by fixing a mandatory minimum sentence had blurred the lines between the legislative and the judicial arms of government.

By stipulating an upper and lower ceiling for sentencing offenders under the relevant penal sections of the Acts, they argued that the legislature was essentially dictating to judicial officers what course of action they must take when sentencing an offender.

Justice Barlow, however, found that the mere setting of parameters within which a court ought to act neither blurs the lines nor creates an obfuscation of the doctrine of Separation of Powers.

One of the arguments advanced by the applicants had been that by fixing a mandatory minimum sentence, the Legislature essentially removed from the sentencing court that discretion which it must possess, thereby rendering the provisions unconstitutional.

The court, however, found that this was not an accurate assessment of the nature of a mandatory minimum sentence and that in holding that view, the applicants are mistaken. The judge pointed out that a court’s task is to examine the legal framework to be sure that while there exists an interdependence, there is no crossing of the line and sentencing remains in the hands of the judicial arm of the state.

In her ruling, Justice Barlow drew the distinction between the prescription of fixed penalty and the selection of a penalty. She cited the ruling in Deaton v AG and Revenue Comrs [1963] IR 170, which found that “The prescription of a fixed penalty is the statement of a general rule, which is one of the characteristics of legislation; this is wholly different from the selection of a penalty to be imposed in a particular case…The Legislature does not prescribe the penalty to be imposed in an individual citizen’s case; it states the general rule, and the application of that rule is for the courts…the selection of punishment is an integral part of the administration of justice of and, as such, cannot be committed to hands of the Executive.”

As a result, Justice Barlow contended that there are sufficient safeguards to keep the powers of sentencing exclusively within the purview of the Judiciary.

Another argument raised by the applicants is that the mandatory minimum sentence prescribed by the Legislature is grossly disproportionate, arbitrary and excessive and therefore amounted to cruel and inhuman punishment.

In addressing the issue, Justice Barlow began with the principle that “the penalty must fit the crime.” It is against this backdrop that she went on to explain that a penalty which is out of proportion with the offence is liable to be struck down on grounds that it offends not only general sentencing principles but also offends the fundamental rights of citizens and is therefore unconstitutional.

Relying on the case of R v Lloyd [2016] SCR 130, Justice Barlow noted that it is not every sentence, even a mandatory minimum sentence, that appears harsh or excessive that amounts to cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment and is therefore unconstitutional.

To be so considered, she expounded, a sentence must be more than merely excessive. According to R v Lloyd, “it must be so excessive as to outrage standards of decency and be abhorrent and intolerable to society.”

She noted, too, that the presence of appropriate checks and balances seeks to ensure that no offender would be subject to the mandatory minimum sentence if the circumstances of his case warrant a lesser sentence.

Justice Barlow said that examples of legislative preservation of the judicial discretion in the face of mandatory minimum sentences can be found in the Precious Stones Trade Act 1982 of Zimbabwe, New Zealand Sentencing Act 2002 and the Misuse of Drugs Act 1990 as amended by the Justice Act 26/1994 of Belize. These Acts, the judge noted, all provide that a court may impose a sentence lower than the mandatory minimum sentence if there are reasons for doing so, which must be recorded.

In this regard, she noted that some pieces of legislation speak of “special reasons” while others simply speak of “reasons.” The Narcotics Act, she said, contains similar provisions. The court identified two examples of special reasons contained in Section 73 (a) and (b) of the Narcotics Act. The first instance refers to the fact that the person was a child or young person at the date of commission of the offence. In the second instance, it speaks to a person convicted for an offence of possession, where the substance is cannabis, the amount does not exceed 5 grammes, and the court is satisfied that it was for the offender’s personal consumption.

Justice Barlow emphasised that these are only two examples and in no way represent an exhausted list of the varied special circumstances with which a court may be confronted and which may warrant the imposition of a sentence lower that the mandatory minimum stipulated by the legislation.

She further stated that in arriving at an appropriate sentence under the Narcotics Act, a court in assessing the circumstances to determine what are special reasons, must bear in mind that narcotics offences are serious offences, and that the Legislature by fixing mandatory minimum sentences was saying that they must be treated with seriousness given the effect that they have on society.

“In each case it is for the sentencing court to make a value judgment of the information that is before that court,” the judge said.

Justice Barlow concluded that Section 73 of the Narcotics Act having addressed special reasons preserves that inherent jurisdiction that every judicial officer must possess at the time of sentencing an accused person.

Justice Barlow questioned whether the time has come for there to be a comprehensive review of the legislation. Such review, she said, would include mature deliberation on whether the mandatory minimum sentence is still necessary and might also address whether the present sentencing regime which mainly contemplates custodial sentences is still necessary.

Fine tuning

Carrington told Sunday Stabroek that he will be doing some fine tuning to the existing version of the bill, after which it will engage the attention of the House. Stressing that he is not seeking to legalise marijuana but rather to remove some of the jail sentences for possession of small amounts, Carrington singled out the absence of funding for rehab as one of the things he has an issue with. The Act provides for an advisory council and a rehabilitation fund but none of these were ever put in place.

Following the sentencing of the farmer, the AFC renewed its call for the removal of provisions of the law that mete out heavy custodial sentences for possession of small quantities of the drug.

Opposition Leader Bharrat Jagdeo said last Thursday that he personally supports the decriminalisation of small amounts of marijuana and members of the PPP/C would be allowed to vote according to their conscience if it is ever put to a vote in the National Assembly.

At the same time, he stressed that he was not in favour of people being caught with small amounts of marijuana going scot-free. “Let us find another set of sentencing. Sentence them to community work – clean up a school compound – to rehabilitation,” he said.

Jagdeo, in a previous interview with Sunday Stabroek, said that the AFC was being “purely opportunistic.” Noting that the PPP/C had addressed the issue in its 2015 campaign manifesto because it was of concern then, Jagdeo stressed that “it is an injustice to have people locked away for small amounts and people who commit more serious crimes don’t even get jail time.”

At a press conference last Friday, AFC Chairman and Minister of Public Security, Khemraj Ramjattan referred to Jagdeo’s comments as “flagrant opportunism.”

Both he and Carrington drew attention to the fact that Jagdeo served as president for 12 years without addressing the issue.

“After being president for 12 years and not doing something …all of a sudden he wants to jump to front,” Carrington said, while Ramjattan added that it was unseemly that Jagdeo was “jumping as if he is the promoter of this bill and when he was in government he did nothing.”

Backpedaled

Carrington, Jagdeo and the Guyana Rastafarian Council all expressed disagreement with Attorney General Basil Williams’s view that there should be a public vote.

Harmon told the media that the issue will require a large consultation of the population and once that is done the government will take a position on the matter.

When asked about this, Carrington made it clear to Sunday Stabroek that he does not support such a move. “It is very silly…the people who don’t smoke will vote against it and the people who do want to smoke…they will vote for it,” he said while noting that a 90% vote against it would suppress the remaining 10%. “I don’t think you should go in that direction at all,” he said.

The Guyana Rastafarian Council expressed a similar view.

“Personally I don’t think we need a referendum on our way of life. The herb is a part of our way of life,” member Ras Leon Saul said.

He added that he is overwhelmed with disappointment as he was personally assured by APNU and AFC prior to the 2015 elections that the existing legislation would be reviewed. He said that Rastafarian community gave its full support to the government and participated fully in the elections process “based on the assurance they had given.”

He said that three years later the coalition party has backpedaled on the pledge given. “They have reneged on their word and it worries me personally,” he said before recalling that during a meeting with Williams in January, 2016, assurances were again given and the council submitted a document that he needed. “Now to hear him speaking the way he is speaking as if he is not too sure of the whole issue, I think that he is being disingenuous,” Saul said.

“I think they will quiver in their boots when they understand we have the potential to become a balance of power …in the next elections… It takes 5,000 votes for one seat and I am sure right now we have more than 5,000 votes in the Rastafarian community and the ganja using community and that is our leverage really,” he stressed.

Council President Ras Simeon called the existing legislation a “draconian law,” which came into being under the former PNC administration. The renamed PNCR is now APNU’s largest constituent.

“A government cannot deny a people their right to practice their culture. It is their constitutional and human right…Government should rethink the issue and make a decision in keeping with people[s] constitutional and human rights,” he stressed.