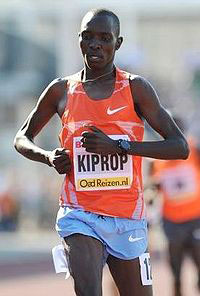

ELDORET, Kenya, (Reuters) – The residents of Eldoret and Iten, considered Kenya’s home of distance running, are hurting following official confirmation that former Olympic and world 1,500 metres champion Asbel Kiprop has tested positive for the banned blood-booster EPO.

The Athletics Integrity Unit (AIU), an independent body handling doping matters on behalf of the sport’s governing IAAF, earlier yesterday confirmed media reports that the 28-year-old three-time world champion over 1,500m had failed a dope test.

The case is now with an International Association of Athletics Federations’ disciplinary tribunal and the 28-year-old Kiprop, one of Kenya’s most decorated athletes, could face a four-year ban.

There was a sombre mood on the Eldoret streets among the local people and in Iten, Kiprop’s home town, where the residents discussed the doping situation in subdued tones.

“This one has hit us where it hurts most,” Moses Kiptanui, a three-time world 3,000m steeplechase champion, told Reuters.

“Marathon runners failing dope tests was almost becoming normal. But when it came to the 1,500m, we were shocked. More so, Asbel (Kiprop), whom many youths looked to as a role model.

“We are mourning. From rural to urban areas, this has shaken everybody to the core,” he said.

Kiptanui, who runs an Eldoret department store, said the lack of tough anti-doping laws coupled with a laxity among Athletics Kenya (AK) officials and Kenyans’ predilection for manipulating rules will bring the country’s top sport to its knees.

“Officials with vested interests, who are attracted by perks, and not the love of the game, are ruining the sport. Even with anti-doping laws in place, we don’t have policing which specialises in anti-doping matters,” said Kiptanui, who blew the whistle on doping problems in Kenya in 2003.

However, Barnaba Korir, a member of the Athletics Kenya Executive Committee, defended the local governing body, saying Kenyans must accept that the country has a doping problem.

“Let us accept that there is a problem and agree on how to tackle it. Blame game won’t help. Kenyans are still in denial yet this doping thing is festering,” he said.

“Athletes are not children. They are responsible for what goes in their bodies. AK only sensitises and educates them on doping matters. They take full responsibility for their actions,” he added.

KIPROP’S ALLEGATIONS

Kiprop alleged that testers extorted money from him, an allegation the AIU did not address. He also claimed that the testers might have interfered with his sample.

The AIU, which was set up to combat all forms of corruption and ethical misconduct within athletics, was satisfied there was no interference with his sample but conceded that Kiprop had been given advance notice that he would be tested.

This contravenes the World Anti-Doping Agency’s guidelines stating that out-of-competition tests should be conducted without notice to athletes.

Kiprop also alleged that he was being pressured to accept that he doped so that he could be made an IAAF ambassador against doping, an allegation the AIU rejected.

Korir and Kiptanui questioned why Kiprop had engaged in what they said was a futile attempt to smear testers and the IAAF.

“Why couldn’t he raise the matter when it happened? Why wait until now to reveal that testers extorted money from him?” asked Kiptanui.

Korir also wondered why Kiprop was revealing so many of the details he should present to the IAAF tribunal.

“The process is ongoing. The best thing Kiprop should do is wait for the appropriate time to argue his case. This was ill-advised,” he said.

Kiprop is among almost 50 athletes from the east African nation, long revered for its distance running pedigree, who have failed doping tests, the most famous being former three-time Boston Marathon champion, Rita Jeptoo and Jemimah Sumgong, Olympics marathon gold medallist in Rio de Janeiro in 2016.

The North Rift Valley towns of Eldoret and Iten, some 350km north-west of the capital Nairobi, rank distance running as their biggest foreign exchange earner.

They take so much pride in their athletes that Eldoret has the name ‘city of champions’, Iten is known as the ‘home of champions’ while Kapsabet to the south, birthplace of twice Olympic champion Kipchoge Keino, is the ‘source of champions’.

In Iten, Jonah Kiplagat, a 32-year-old motorcyclist who retired from road running due to injury, said the residents of the hamlet on the edge of the picturesque Kerio Valley were commiserating with Kiprop.

“He is our hero here. When we see his car zooming past, we are proud of him and the fame he has brought our town. This came as a shock to us,” he said.

Social clubs in Iten, mostly frequented by sportspeople, were not doing much trade on Friday. The Mindililwo area where Kiprop built a training camp was like a ghost town.

Situated on the Iten-Kapsowar road where two other celebrated athletes, marathon runners Wilson Kipsang and Edna Kiplagat, live, the news was on everyone’s lips.