The Snowflakes Sail Gently Down

The snowflakes sail gently

down from the misty eye of the sky

and fall lightly, lightly on the

winter-weary elms. And the branches,

winter-striped and nude, slowly

with the weight of the weightless snow

bow like grief-stricken mourners

as white funeral cloth is slowly

unrolled over deathless earth.

And dead sleep stealthily from the

heater rose and closed my eyes with

the touch of silk cotton of water falling.

Then I dreamed a dream

in my dead sleep. But I dreamed

not of earth dying and elms a vigil

keeping. I dreamed of birds, black

birds flying in my inside, nesting

and hatching on oil palms bearing suns

for fruits and with roots denting the

uprooter’s spades. And I dreamed the

uprooters tired and limp, leaning on my roots –

their abandoned roots –

and the oil palms gave them each a sun.

But on their palms

they balanced the blinding orbs

and frowned with schisms on their

brows – for the suns reached not

the brightness of gold!

Then I awoke. I awoke

to the silently falling snow

and bent-backed elms bowing and

swaying to the winter wind like

white-robed Moslems salaaming at evening

prayer, and the earth lying inscrutable

like the face of a god in a shrine.

Gabriel Okara

When anthologist Victor Ramraj edited Concert of Voices: An Anthology of World Writing in English published by Broadview Press in Canada he described its “intention” as “both to provide an alternative text to anthologies of traditional and established writings” and “to complement” the many other anthologies of world writing that were already well known. He exhibited such a wide range of national literatures and styles that this anthology gives “sociological or anthropological insights” into different peoples and cultures, demonstrating quite a “literature without borders”.

We have already shown the example of Edwin Thumboo and how/why he is seen as the pioneer – the creator of native Singaporean literature. The remarkable poem “Ulysses at the Merlion” that looks on the surface very much like an echo of Greek mythology, Homer and other modern and Victorian poets, is actually a deeper creation of native verse. This tension between the international – the wide world of literature – the English poetry, and the Singaporean is demonstrated in other literatures and writers represented in the anthology.

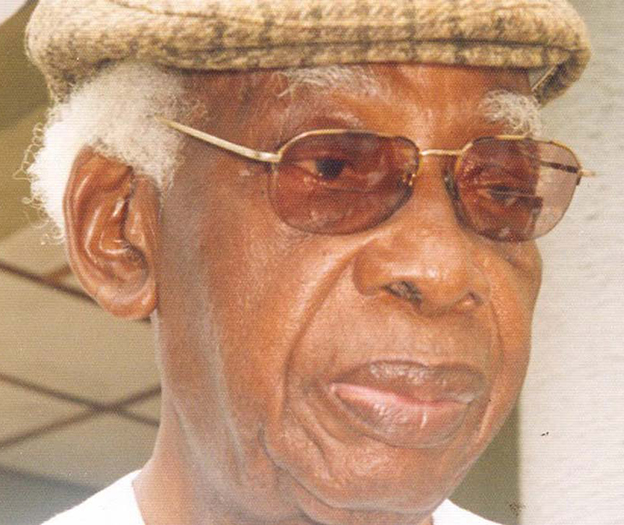

Outstanding among them is Nigerian poet, novelist and playwright Gabriel Okara. There is significant similarity between the work and the place of Okara and that of Thumboo. Okara did for African literature what Thumboo did for Singaporean. Okara is regarded as the unsung, unfabled father/founder of modern African literature in English. From translations of Ijaw traditional poetry into English in the 1940s, he progressed to publishing his own verse in English carrying the West African Ibo culture with it.

In an earlier analysis, we presented Okara’s “Call of the River Nun” – the poem that started off the rise of the literature in 1953. It also earned the poet the title of ‘Negritudist’, making him the equal of such pioneers as Leopold Sedar Senghor, Aime Cesaire and Leon Damas, the founders of Negritude, and even with Wole Soyinka, the foremost mover of African poetry and drama since the 1960s.

Okara grew up on the banks of the River Nun, a branch of the mighty River Niger whose wide and multi-streamed delta is the base of the Rivers State and Nigeria’s South-East Region. That poem inspired by the river and the Niger Delta is steeped in the landscape, but also in tradition, myth and identity. Okara was not a part of the academy of leading writers and academics like Soyinka and John Pepper Clarke but deserves a place in the pantheon beside them.

His experimental novel The Voice (1964) is one of the great works of African fiction and no less than the celebrated works of Chinua Achebe. Yet its lyrical quality and linguistic inventiveness compare it with other pioneering works such as The Palm Wine Drinkard by Amos Tutuola. The Voice has a quality of narrative that is innovative in its use of language and consciousness which makes it stand out as literature with a distinct identity.

“The Snowflakes Sail Gently Down” was supposedly written in the USA, while Okara was studying journalism at Northwestern University. It might be a poem of nostalgia, but its post-colonial element is strong as it reflects on exile in a way that makes absence from home a distinct condition of alienation. The picture of the foreign environment is decidedly deathly as opposed to the richness of the native African. The elms are “winter-weary” and dying; “winter-stripped and nude” – the starkness of the trees, skeletal after the fall of all their leaves before winter. These are contrasted with the images of his dream – “not of earth dying and elms a vigil keeping”. There is life in his dream as much as there is resistance. The “oil palms” are “bearing suns for fruits” while the roots “dent the uprooter’s spades”

These are images of strength and vibrancy associated with African home and roots, but he is dreaming of them while he is away in the wintry metropolis. This absence is associated with negative effects, but with life-giving powers:

“I dreamed

The uprooters tired and limp, leaning on my roots –

their abandoned roots

and the oil palms gave them each a sun”.

Even the pictures of the winter landscape after he wakes from his dream is painted in the pictures taken from the culture and environment of Nigeria which remains more colourful. These are of “white-robed Moslems salaaming at evening prayer” – a spectacular sight at mosques or other gatherings in Nigeria where several dozens of men may be seen worshipping together in what is always a memorable spectacle.

It is in a poem like this one that we can see the comparability of Okara with Soyinka, for instance, in his post-colonial verse, and his poems of resistance to Britain, to colonialism and to racism as we get from Soyinka’s “Telephone Conversation” as one example.

Okara’s “The Snowflakes Sail Gently Down” joins the anti-colonial literature of Achebe, of Soyinka and others credited with the phenomenal rise of African post-independence literature after the 1960s. However, this considerable movement was advancing along the highways smoothly paved by the pioneering work of Okara since 1953.