Last week’s column addressed two of five topics singled out earlier for comment in order to highlight their significance from an economic perspective; namely 1) Government take/developmental benefits/economic profit; and 2) accounting for costs. Today I focus on two others namely: the measurement of hydrocarbons resources & reserves; and, tax compliance. Next week I shall provide wrap-up comments on the petroleum project’s life cycle. I start today’s, offering a concluding comment on last week’s discussion of topic 1), omitted because of lack of space.

Government take

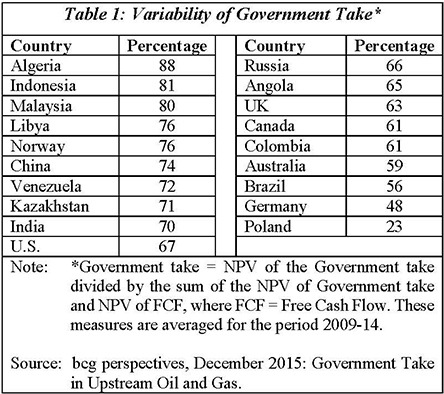

Recent estimation of Government take for 19 countries (averaged over the period 2009-2014) is shown in Table 1. The information reveals significant variability. As previously explained, Government take is a vital fiscal metric, but is not accorded great priority by private investors. Private investors concentrate instead on net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR) and the profit ratio (PR). Such private profitability measures are expressed at discounted or undiscounted values.

There is regular misuse of this measure in the local media. Therefore, it should be advised that when governments discount these values, they are using a social discount rate (which is a subjective metric) while when firms do so they use a market (objective) discount rate. The former rate is routinely higher than the latter. Table 1 shows the information mentioned above.

The note explains how Government take has been calculated in the Table. Further, the same measure of Government take has been applied to every country. And, the FCF covers the standard three-fold source of cash flows: operations, financing, and investing.

The range in the data is significant; from a low of 23 per cent (Poland), to a high of 88 per cent (Algeria). Other descriptive statistics reveal the mean (average) value is 66.16; the median value is 67; and measures of variation show a standard deviation of 14.2.

Resources, reserves

In the natural resources economics literature, hydrocarbons resources represent the volume of hydrocarbons estimated to be in the ground. Such amounts may or may not be economically recoverable. Reserves are, however, those resources that are expected to be commercially/economically recoverable, based on prevailing technology and market expectations. These estimations impact the financial statements of petroleum enterprises, especially in the areas of 1) depletion/depreciation/ amortization 2) decommissioning, 3) impairment and 4) the allocation of purchase price.

Reserves estimation

Economic principles have, more specifically, guided hydrocarbons practice in the area of reserves assessment. There is absolutely no doubt that, in practice, oil and gas companies rely on petroleum reservoir engineers, and sometimes geologists, to prepare their reserve estimates. It is a complex process that requires “analysis of information about the geology of the reservoir … the surrounding rock formations and analysis of the fluids and gases within the reservoir … the reservoir pressure, and other relevant data”. Economic principles related to expected commercial viability, given the state of technology guide the classification of hydrocarbons reserves.

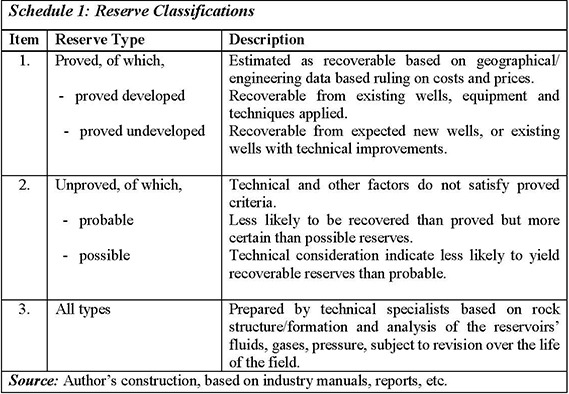

The standard classification of such reserves used is shown in Schedule 1. Generally, reserves comprise 1) proved reserves (both developed and undeveloped) and 2) unproved reserves (both probable and possible).

Tax compliance

Experiences with oil majors on a worldwide basis have revealed past practice whereby corrupt activities by these enterprises, and, all too frequent in collaboration with local political, economic, business, and government service elites, have led to enrichment of a few and defeated the expectations of the vast majority. I have already discoursed on this topic last year, when I dealt with the resource curse and the negative experiences of several small poor open and under-capacitated countries. Institutionally and otherwise, these countries have shown great failure at overcoming these challenges. Several optimistic writers presently speak of the opportunities for a steep learning curve that these countries could benefit from. I am however, less sanguine, simply because the oil majors also benefit from improved techniques that serve their longstanding goal of tax evasion.

It is thus important when dealing with this threat, to recognize the distinction between tax avoidance and tax evasion. Tax avoidance does not involve breaking any laws, while tax evasion does. I personally believe, however, almost every economic agent (from the largest conglomerate to the individual taxpayer) would avoid paying taxes, if this does not require any laws to be broken. An efficient tax administrator should therefore, take this condition as given. Unfortunately, too often critics of the oil and gas companies fall for the diversion of pointing out what are “tax avoidance measures” as being immoral and illegal!

The only effective way to curb tax evasion is through international and regional cooperation. Such cooperation should be based on tracing movements of funds and a willingness of all state parties to share the proceeds of tax evasion.

In conclusion, while economists recognize tax evasion as illegal and involving corrupt behaviour by economic agents, they also see tax avoidance as the rational choice for all economic agents seeking to be efficient, optimizing, and maximizing!