Today’s column starts with a wrap-up of my response to the letter sent to Stabroek News by the author of Open Oil’s financial modeling exercise of Guyana’s 2016 PSA. After that, it commences to critique that exercise. For the wrap-up, I offer two brief comments for readers’ benefit.

First, Open Oil’s Draft Report and Financial Statements, 2015 states: “OpenOil is a limited company incorporated in Germany during October 2011. It was founded as a social enterprise (my emphasis) and under its articles of incorporation it is licensed to engage in consultancy to improve governance of the energy sector”. Initially, I had sought to by-pass this description, as I felt at the time of writing, it could be confusing for the general readership of this column.

Now, having reflected on it, I am compelled to inform readers that the International Comparative Social Enterprise Models (ICSEM) project, 2015 notes: “the term social enterprise appeared in Germany for the first time in the 1990s in the context of transnational research projects initiated with the help of the European Commission … but only a small group of researchers participated.” Furthermore, “the terms social economy and social enterprise are not legally defined nor understood in detail in Germany today”. (Source: Social Enterprise in Germany: Understanding Concepts and Context, Working Paper No.14, 2015). Readers can see why, in the interest of space, I sought to avoid engaging Open Oil’s formal socio-legal structure.

Second, Open Oil enjoys collaborative relationships with two well known foundations that were established in the early 2000s. One is the Shuttleworth Foundation, of South Africa, established in 2001. That Foundation retains a 15 percent option in the equity of Open Oil. The Foundation describes itself as “a small investor that provides funding to dynamic leaders who are at the forefront of social change. We look for social innovators who are helping to change the world for the better and could benefit from a social investment model with a difference”.

The other is the Omidyar Network. This is a “philanthropic investment firm composed of a foundation and an impact investment firm”, established in 2004. It is “founded on the fundamental belief that every person has the power to make a difference”.

Such associations suggest Open Oil is well positioned to derive significant value-added from assessments, evaluations, and critiques of its activities. In the next Section, I start my critique of its financial modeling of Guyana’s 2016 PSA.

Critiques

While the several critiques to follow are given randomly, the first of these is, in many ways, the most important. The reason for this being its focus on both the logical weaknesses inherent to all financial/economic modeling as well as those modelers who fail to declare upfront appropriate cautions, when publicizing their results, particularly to non-modellers/non-specialists. Financial models need to capture the essence of the reality that is modeled. Given the vastness of detail required for modeling of petroleum projects plus their inherent uncertainties, this requires cautioning readers about the predictive reliability, which should be attached to results.

To see how important this caution is, readers should recall my earlier presentation on the World Petroleum Council’s description of petroleum projects. Simply put, a petroleum project links petroleum finds/accumulations to decisions and budget allocations for the development of oil fields (of a wide variety of types). These fields represent specific maturity levels, in order to arrive at decisions as to whether to proceed or not with spending resources bringing the project to commercial production. A project can be an individual field or reservoir, (like Liza 1 in the Stabroek block), an “incremental development” of a field, or the “integrated development” of a group of several fields/reservoirs that are held under common ownership.

As is widely recognized however, “petroleum companies generally make the decision for a certain petroleum project on the base of economic models” (K. Shereith, Doctoral Thesis, Berlin, 2016). This thesis references the three broad approaches such models use for risk assessment and the identification of problems that could emerge during a project’s life so as to support its efficient execution/completion.

That thesis has evaluated the Eco Petro _ Model, as a deterministic model petroleum companies use to evaluate projects. The thesis focuses on two case studies: the use of the Eco Petro _ Oil “model in an OPEC country operating with a production sharing contract” and a non-OPEC country utilizing the “concessionary system”. Like the FAST Open Oil financial model evaluation of Guyana’s 2016 PSA, it had to confront the central problems of all petroleum modeling. These problems are widely recognized as originating in the recognition that “the economic structure of the petroleum industry differs strongly from other industries”.

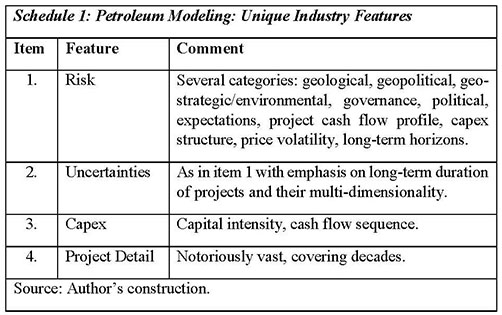

Those special features have been discussed on several occasions before, and are summarized in Schedule 1 below. The Schedule reveals the industry faces enormous risks and related uncertainties. These are found in every dimension of its operations: ranging from geological and environmental, through economic/financial (prices, cash flow, capital intensity and so on) along with socio/political (geo-strategic, governance/corruption) over a long-term horizon. Indeed, most projects last over several decades. And, in the case of Open Oil’s financial modeling exercise, Liza 1, in the Stabroek block, lasts for over four decades, 1999 to 2040.

From all that has been said so far on this critique, two points are clear. First, operationally, most petroleum companies are reputed to “make the decision to invest in a certain petroleum project based on economics models”. These are typically constructed as spreadsheets, which are “prepared by internal economists in the company or by consultants based on the data provided by their engineers, geologists, and so on.” (Shereith, 2016)

Second, investment decision-making for petroleum projects is very complex, mainly due to the features noted in the Schedule. Economic/financial modelling aids in decision-making. However, by their very construction, models have limitations. And, this therefore, must always be openly admitted, by those recommending their use.

Next week I continue this critique.