Introduction

Today’s column continues to advance my overall assessment/evaluation of Guyana’s Green Paper, which proposes to establish a Natural Resources Fund (NRF) next year. Last week’s column had made two observations, which are, by a distance, the most important from the perspective of an overall assessment/evaluation.

To recall briefly, the first was that the NRF represents state-owned capital, generated from the export of Guyana’s natural resources. The NRF, however, like similar sovereign funds, is designed to operate within a universe of private investors, responding to private risk-return incentives in global markets. The second observation was that in order to survive in global markets, such state investments have to be organised in a manner that avoids challenging the dominance of ruling private risk-return incentives in these markets. Both these observations apply, de rigeur, due to the sheer current size of such state-owned funds (US$8.1 trillion total, of which natural resource-based funds are US$4.4 trillion or 54 percent).

Four additional observations follow in today’s column. However, I do not believe these are nearly as weighty, as the two introduced last week. Next week I shall conclude this evaluation and then comment broadly on governance of the NRF.

1: Daily Rate of Production (DROP)

The first additional observation is that the production test incorporated in the Green Paper lacks ambition. It is far too conservative, even for Authorities that are seeking to dampen public expectations! I shall return to this issue in greater detail, when I advance the Buxton Proposal and my proposed development “roadmap” for Guyana’s coming petroleum sector. I shall argue then that, based on published geological surveys/estimates of Guyana’s petroleum reserves completed over the two previous decades, that it is insanely conservative to set the DROP for the production test at the three ranges of: Low—less than up to 200,000 barrels per day (bpd); Medium—200,000 and up to 400,000 (bpd); and, High—400,000 (bpd) and more.

Readers should recognise these figures set the level of the NRF’s ambition. They are largely determinant of the value of inflows and, therefore, potential NRF withdrawals. And, this is the reason why a more realistic range remains important for the outcome!

2: Primary Purposes

The second additional observation is that Guyana’s NRF, similar to others, has identified three primary purposes. These are, firstly, (1) stabilization of fiscal revenues; inflows and public spending. This purpose is crucial, given the traditional volatility and stop-gap patterns of oil supply, demand, inventory holdings and prices. The smoothing of inflows and related spending through a Fund is of immense macroeconomic advantage. This concern is linked to the “top-10” development challenges I posed, especially as they relate to the presource and resource curses, along with the Dutch Disease threat.

The second and third purposes, respectively, that is 2) state investment in development projects and 3) intergenerational equity, are more problematic. Empirical data reveal poor outcomes for Government development spending in small, poor, open economies. Fortunately, there is general agreement about the need for and, indeed, the availability of measures for improving on this outcome.

However, I had earlier observed (September 16, 2018) the Australian Intergenerational Report (2002-3) had stated: “There are competing views about intergenerational equity: “what it means, and what exactly it is that needs to be sustained into the next generation. And consequently, there are competing views about intergenerational obligations, if any, the goal of sustainability imposes on the current generation”. Obligations to future generations always compete with justice and fairness to the present generation. And, this issue is not a simple “zero-sum game,” where one generation’s benefit is another’s loss! In this sense, intergenerational equity is not straightforward and consequently remains a hotly contested theoretical notion.

Additionally, readers should note: if average per person real GDP shows any positive growth over generations, which is typical, then future generations will be, on a per person real basis, richer. I make this observation before, not to encourage disregard for future generations’ well-being, but mainly to ensure that in its pursuit, society does not overlook justice to the needs of the present generation.

3: Key Variables

The third additional observation relates to readers reporting that they find the fiscal rules, as described in the Green Paper, opaque. My advice has been to encourage focus on the key features, which I define as follows:

Timing of withdrawals from the NRF

Amount of withdrawals from the NRF

Conditions for the inflows and outflows to the NRF

Disclosures/content of external assets

Governance (oversight, surveillance, private incentivising etc.)

Asset composition (earnings, illiquidity, risk, etc.)

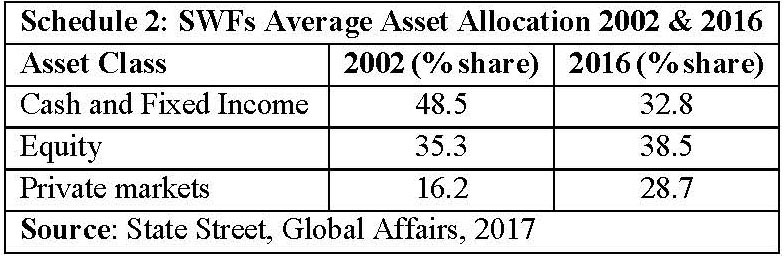

The International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) identifies five SWF goals. These provide a useful guide to their intended operations and concerns over their governance (See Schedule 1.)

4: SWFs Average Asset Allocation

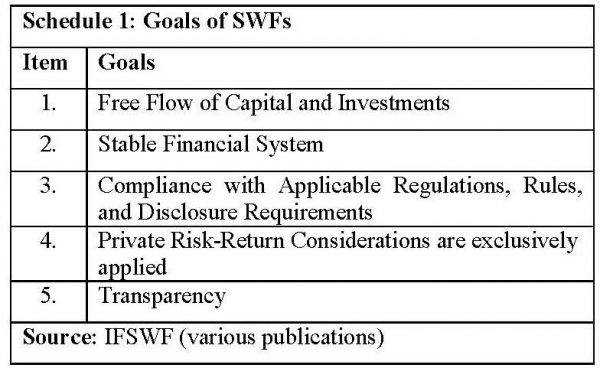

Finally, it would be useful at this point to observe the most recent reported data on the average allocation of assets held by SWFs worldwide. For convenience, comparative data for 2002 and 2016 are shown in Schedule 2 below.

The data in Schedule 2 reveal that while equity constitutes the largest class in 2016 (38.5 per cent), this is an improvement on 2002, when it constituted 35.3 per cent. In 2002, “cash and fixed income” constituted nearly one-half of all assets (48.5 per cent); and, by 2016, this was just equal to one-third. The strong growth of private markets is very evident, rising from 16.2 per cent in 2002 to 28.7 per cent in 2016. This group of assets included private equity, real estate, and infrastructure (State Street, Global Affairs 2017). These observed portfolio shifts reflect a mixture of a longer-term bias in assets portfolios, towards greater risk and less liquidity.

Conclusion

Next week, I’ll offer comments on key aspects of governance. Afterwards, I proceed to wrap-up this discussion of the Green Paper. The following week, I shall consider the permanent income hypothesis, employed as a fiscal rule to govern Guyana’s NRF.

Send comments to cythomas77@yahoo.com