Before we get into whether their assessment is realistic, let’s listen to what they are saying.

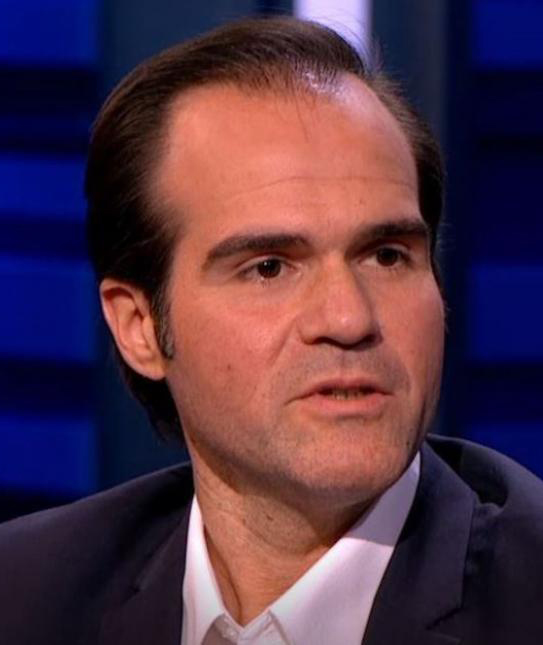

Claver Carone, whose official title is director of the National Security Council’s Western Hemisphere Affairs office, told me that U.S. economic sanctions on Venezuela’s PDVSA oil monopoly will cripple the Maduro regime.

U.S. oil imports represented 85 percent of the Maduro regime’s cash income, which means he no longer will get access to about $11 billion a year, he said. The sanctions on PDVSA, which started only three weeks ago, soon will take full effect, and the Maduro government “will no longer have access to cash,” he said.

“Let’s face it, nobody is loyal to Nicolás Maduro because of ideology, or because of religion. His whole structure to usurp power has been based on financial dealings with the military hierarchy,” Claver Carone said. “That’s basically over.”

Maduro is now sending emissaries all over the world trying to withdraw deposits from foreign banks, but new U.S. sanctions on foreign financial institutions that transfer money to Maduro’s regime will make that increasingly difficult, he said.

But, I asked, won’t Russia and China bail him out with emergency loans?

“No, I don’t think so,” Claver Carone responded. “Maduro owes more than $20 billion to China and more than $10 billion to Russia. Any oil export that Maduro makes to these countries is being used as payment for Venezuela’s debts. So none of these countries will give him any cash.”

Asked how long Maduro can hold on to power with his current reserves, Claver Carone wouldn’t speculate, but said that, “He’s on a dead-end street. There is no way in which Maduro can manage the country or maintain his bribery network without access to state companies’ income.”

Other U.S. officials echo the same optimism, but some caution privately that, for the U.S. sanctions to be fully effective, they will have to be accompanied by similar measures from the 28-country European Union.

So far, most European countries have followed the United States in recognizing National Assembly president Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s legitimate leader, but few have imposed economic sanctions on regime-controlled state companies or the banks that do business with them.

Much of the Maduro regime’s money is in European banks, especially in Spain, U.S. officials say.

“The key country is Spain,” one U.S. official told me. “That’s the place where most top officials of the Maduro dictatorship have their money, their second homes and their families. And that’s the country where they all want to move to.”

Venezuelan opposition leaders have tried to sway Spain’s Socialist government into offering asylum to top Venezuelan military officers as part of a potential political agreement to restore democracy. But Spanish government officials reportedly are reluctant to do so, in part for fear of lawsuits from Spanish prosecutors who may charge them for giving shelter to human-rights abusers.

Spain is scheduled to hold presidential elections on April 28. If a conservative coalition wins, it may be more inclined to impose economic sanctions on Venezuela and offer asylum to top Venezuelan defectors as part of a political negotiation.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration is in no position to sway the Europeans to step up sanctions on Venezuela. Trump is almost universally hated in Spain, Germany, France and other key European countries because, among other things, he has repeatedly threatened to leave the NATO alliance, wants to slap tariffs on European goods and has insulted several European leaders.

Also, Europeans are nervous about Trump’s statement that “all options are on the table” in Venezuela. They don’t want to be part of anything that could potentially lead to a U.S. military intervention there.

U.S. officials’ upbeat forecasts about Maduro’s possible downfall may be wishful thinking, psychological warfare or just empty political rhetoric to win Venezuelan-American and Cuban-American votes in Florida.

But if Trump really wants to bring down Maduro, he will have to resort to the very multilateral diplomacy for which he has criticized his predecessors and coordinate escalating U.S., European and Latin American nations’ sanctions against Venezuela. Without these countries’ help, Maduro’s political demise could take longer than expected.