In last week’s column, I had introduced the concept of the break-even price. I then applied it to Guyana from the perspective of those private businesses that are contracted to produce its oil and gas on behalf of its legal owners, the Government of Guyana (GoG). As was earlier indicated, presently two major consortia of foreign interests are principally responsible contractually for on-going exploration, as well as the development, production and marketing of its oil and gas! These two consortia are led separately by Exxon Mobil and Tullow Oil.

The focus of today’s column however, shifts quite a bit to what the literature terms as Guyana’s “fiscal break-even price” for its petroleum exports. In its simplest essence, this fiscal break-even price reflects the perspective of the GoG as it is the legal owner of the petroleum resources that are being exploited. This perspective holds, regardless of whether Guyana’s oil and gas resources are being developed as it is now, by consortia of external business, or through a specially created government-owned National Oil Corporation (NOC).

This is indeed the logic which lies behind last week’s concluding observation that the introduction of fiscal as a descriptor of the break-even price makes the concept a “social” or “national” price. As I shall reveal as I continue, this is no longer a price determined in the market place for private businesses. From such a perspective it therefore becomes a normative price. In other words, it reflects what the GoG thinks it ought to be, as explained in the next Section.

The Fiscal Break-even Price

Economists define Guyana’s fiscal break-even price as the minimum price for a barrel of crude oil equivalent (boe) that the GoG requires in order to obtain revenues from selling its petroleum, which it deems sufficient to meet its spending requirements in full. The requirements will be based on the several policies, plans, programmes and projects that the GoG intends to implement during a given budget period while maintaining a balanced budget. This is termed a normative price, because, as described here, it is based on the price government feels it ought to receive, rather than a price which is determined objectively (by demand and supply) in the market place.

Given such a definition, it follows, therefore, that if the price obtained per barrel equivalent (boe) is below the fiscal break-even price, then this would yield either: 1) a national budget deficit, if spending is to be maintained at the contemplated level; 2) a reduction in Government’s spending; or 3) some combination of both. If the opposite circumstance occurs, which is, the price obtained from the sale of petroleum exceeds the fiscal break-even price, then logically also, the Government can: 1) increase spending; 2) carry a budgetary surplus; or 3) utilise some combination of both these outcomes.

Popularity

The practice of periodically estimating fiscal break-even prices for major oil exporters has become a standard feature of global economic, financial, political and governance (regulatory) reporting in today’s globalised energy environment. There are several benefits to be obtained from this practice. The evidence suggests such benefits include: 1) offering a convenient proxy for industry analysts to assess risks facing oil and gas producers; 2) providing comparators of such prices, across the key global energy suppliers in order to provide insights when assessing global energy output, demand, and indeed, the likely energy mix. From such assessments, analysts provide improved estimates of both the energy-mix, and its likely geographical distribution. Further, the principal players in today’s global petroleum sector, rely on estimated fiscal break-even prices to project the emerging global configuration of energy market balances. Indeed, several governments utilise such estimates to assess their own fiscal capacity. Today’s industry practitioners routinely consider the fiscal break-even price as one of the most essential tools for assessing both fiscal space and for framing recommended fiscal policy reforms.

As matters presently stand, fiscal break-even price indicators have become influential worldwide. Several institutions independently publish their own estimates of these on a regular basis. For the sake of completeness, it is worth observing that such estimates are treated as central indicators for understanding the dynamics of: entry-barriers-sales-cost-output-price-demand-profits, and target-setting in the global petroleum sector.

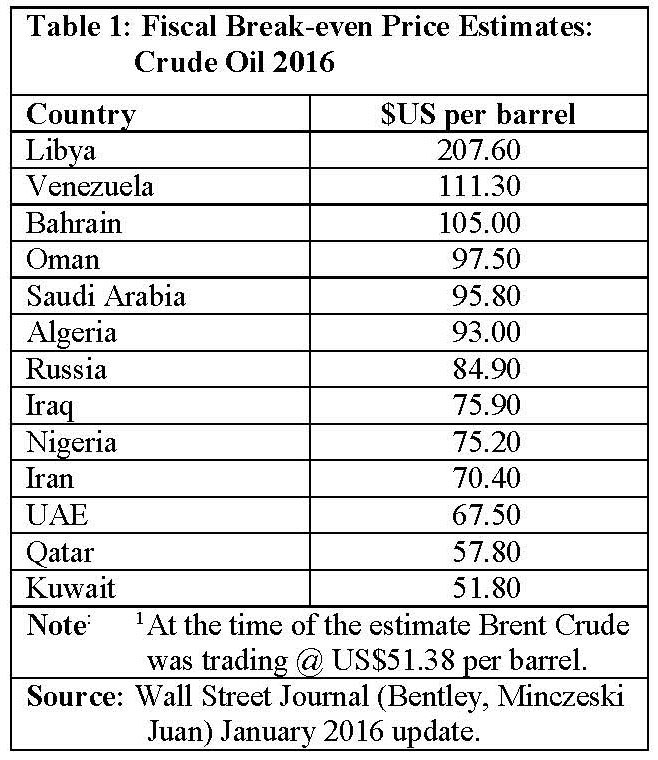

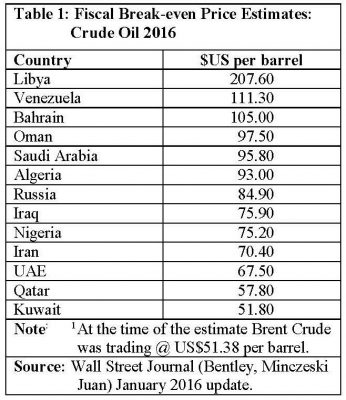

Table 1 provides recent estimates of fiscal break-even prices for a sample of 13 countries from among the top 20 crude oil exporters. The Table’s data reveal wide variation

Methodological Problems

In the earlier columns, I had stressed that the concept of the fiscal break-even price poses several methodological challenges in its determination. These include: 1) Variance between actual and projected crude oil production and exports; 2) Variance between planned and actual government spending; 3) Unexpected changes in national exchange rates (Such changes impact the value of the local currency as these prices are usually denominated in US dollars); 4) Effects of economic, political, social, and other shocks (including natural and man-made disasters); and 5) Differences in data quality are quite significant given the wide variety of sources producing these indicators: official, unofficial, firms individual researchers, regional and international bodies and their various applied techniques.

Conclusion: Guyana’s fiscal break-even price

There is no estimate of Guyana’s fiscal break-even price because the country has not yet had First Oil. It is likely though that the GoG will seek to define this price quickly after First Oil.

Next week, I shall wrap-up the discussion of Guidepost 6 in Guyana’s Petroleum Road Map from its dimension of “getting petroleum revenues.”