In what will be seen as a cautionary tale for this country and its impending oil wealth, the IMF 2019 staff Report on Guyana has cited pitfalls from Trinidad and Tobago and Ghana to underline what can go wrong.

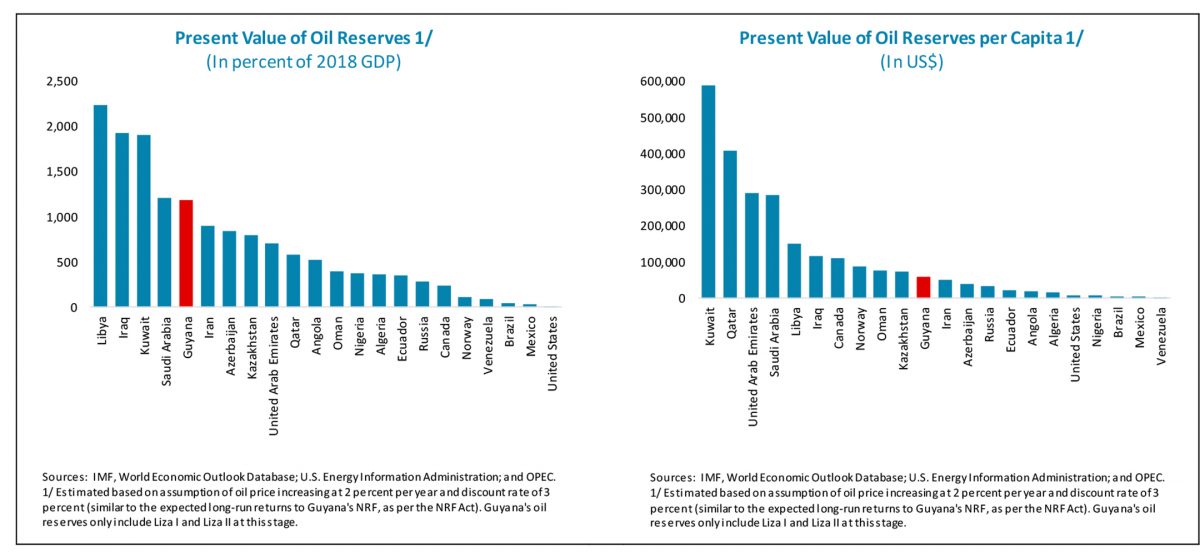

In its report released on Tuesday, the IMF said that income from Guyana’s oil has the potential to transform the economy but will need to be managed effectively to limit macroeconomic distortions related to Dutch disease and governance weaknesses. It said that oil production is expected to begin in the first quarter of next year, averaging 102,000 barrels/day (bpd), and rising to an average of 424,000 bpd in 2025.

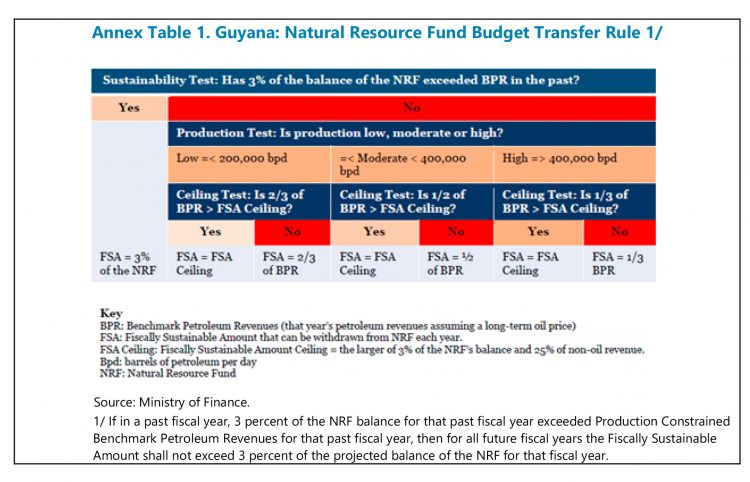

It added that the main direct effect of the oil sector on the domestic economy will be through fiscal revenue and its use. The report noted that the authorities have legislated a Natural Resource Fund (NRF) Act 2019 which provides a framework for establishing a natural resource fund, a Public Accountability and Oversight Committee to report on the Fund, and a transfer rule that determines fiscal transfers from the NRF to the budget. In the event of a delay in initial oil production, the report notes that NRF Act does not allow the front-loading of oil-financed spending in advance of the securing of oil revenue.

In the case of Trinidad, the IMF said that rapid scaling up of public expenditure risks fueling macroeconomic distortions, inflationary pressures and the eroding of competitiveness. In the last few years, Guyana has been cautioned about spending prudently and only after the oil revenue actually enters the budget. The IMF said that Trinidad and Tobago benefited from large increases in oil prices in the 1970s.

“Surpluses from oil revenues enabled the government to invest in

large projects—in sectors such as steel and petrochemicals—with the intention of reducing the country’s dependence on oil. As domestic expenditure expanded rapidly, and wage awards exceeded increases in productivity by a significant margin, inflationary pressures emerged, eroding the competitiveness of the non-oil economy. Prices of non-tradables, such as real estate, rose sharply in relation to prices of imports and exports. In 1982/83, as global oil prices weakened, and petroleum output declined from peak levels in 1978, the country began to face serious economic problems”, the IMF noted.

It said that the overall public sector fiscal position in the Twin-Island Republic shifted from a surplus in 1981 to deficits totalling around 15 percent of GDP in 1982/83 as outlays rose and the decline in oil revenues more than offset the rise in other revenues. Four fifths of the public sector deficit originated from central government operations, underlining higher public sector wages and transfers to cover operating losses and capital outlays of the nonfinancial public enterprises.

The IMF said that the Trinidad economy contracted by 7.5 percent year on year in 1983 as the decline in petroleum output was exacerbated by the fall in the non-petroleum sector.

“The country became increasingly uncompetitive with an appreciating real exchange rate, leading to considerable pressures on the balance of payments. Consequently, the large stock of foreign exchange reserves accumulated during the oil boom was depleted. Significant adjustment started in mid-1980s when the government tightened import and exchange controls and devalued the currency”, the IMF noted.

Ghana

Citing Ghana’s case, the IMF said that the public debt could grow unsustainably at the same time as the sovereign wealth fund (SWF) accumulates in the absence of a medium-term anchor that is consistent with SWF withdrawal rules.

This is another warning that Guyana has heard often in recent years.

The IMF noted that Ghana started producing oil in 2011 and established the Petroleum Revenue Management Act (PRMA) in the same year. The start of oil production attracted major inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) and boosted the economic growth. As its per capita income rose to US$1,879 in 2013 (US$1,358 in 2010), Ghana rose to a Low Middle-Income Country (LMIC).

“However, the change into LMIC status constrained the country from accessing grants and concessional financing, and the rapidly rising public debt had also resulted in higher interest payments. In addition, the rapid increase in public wage bill and other current spending more than offset the increase in oil revenue. The rigid legal framework in the PRMA also did not allow the government to accommodate unexpected large shocks, forcing Ghana to continue financing large deficits with debt while transferring the oil revenues to the petroleum funds”, the IMF said.

In 2014, following the sharp drop in world oil prices, Ghana’s exchange rate depreciation increased input costs and placed pressure on growth, particularly in the industrial and services sectors. This prompted the government to request an IMF programme in 2015.