It could well be that my time as a musician has left me prejudiced, but I have long felt that there are striking examples of creative genius about in the musical world that we glide by without noticing or appreciating what is sitting right there before us until some circumstance or occasion brings the condition clearly into focus. Just in these past two months, for example, I have been jolted (and that’s not too strong a word) by some examples that came to me in diverse ways but each making the point of these wondrous instances of music mastery, unfortunately almost forced into the background by the sheer volume of music that comes at us these days in so many forms. One of them for me recently was to totally accidentally rediscover the singular vocal talent of American songstress Norah Jones. In an online collection of memorable songs, two performances by her stood out for me: I Don’t Know Why, and Lone Star, certainly for the highly skilled examples of classic song-writing they are, but also, equally, for the masterful vocal performance by the singer. Norah has the ability – another singer who has it is the Italian Andrea Bocelli, as does Nina Simone – of delivering music as if the song is singing her, rather than she singing the song. There is seemingly no effort, the sound is coming from some other source than her, and the warmth and the feeling she generates is striking – one cannot find a flaw in the rendition. It is simply mastery. In a different genre, also in recent weeks, I came across again a song I have long known as a classic – this one from the Trini calypsonian Lord Blakie, doing his hilarious Chinese Accident calypso, bridging Caribbean dialect and sense of humour in one fell swoop; another example of Blakie’s mastery who is probably better known for SteelBand Clash, but I see him shining brightest in his Chinese calypso.

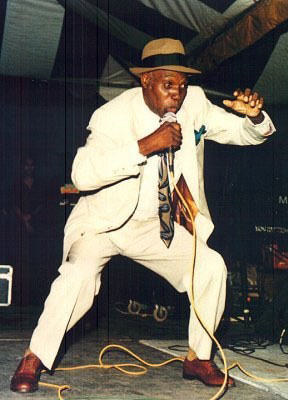

I pause to confess that what I have said above is actually an introduction to my main topic today, which is the Trinidadian calypso legend, the late Lord Kitchener, and his name, I also confess, came into my mind following a recent email from a long-time friend in Grand Cayman, another Trini musician, Gaston Maloney, who sent me a video of Kitchener doing his classic Guitar Pan, paying homage to that lesser acclaimed component in steelband music. There are many approaches one can take in rating the quality of musical composition but one of them at the top of my list would be that both the musical and the literary genius must be functioning in tandem, and in that regard Kitchener is a standout in our music, and that’s ultimately my point here today. I am assuming readers are generally familiar with Kitch’s more well-known compositions – Audrey; Sugar Bum Bum; Pan in A Minor; etc. – but for that combination of which I speak – musical notes and lyrics – Kitch is my boy. In the song Guitar Pan, he is educating us to look beyond the obvious tenor man, or the double bass, and he does it while making us want to dance at the same time. I have heard it said that Kitch’s songs are ready made for pan because the songs were written on pan. I asked him once about how he wrote, but unfortunately before he could answer he was called away to some other matter and we never resumed the conversation, so I don’t know if in fact he composed on a tenor, but the cascading notes that are a feature of songs like Pan in A Minor and Guitar Pan, do sound indeed as if made on pan for pan to play.

Overall, it is clear from his recordings that this is writing from a particular well, as all great writings are, but as to how they came about I cannot ultimately say. I can only say that long before Pan in A Minor burst upon us, I remember like yesterday the first time I heard Kitchener’s calypso Jericho, about the Lopino area in Trinidad with an exceptional band, in which there is a stunning interval line leading to the chorus, with the words, “everybody want to know the Jericho from Lopino.” If you know this song, you know what I mean. The way Kitch presents that line, as if it’s truly meant for a tenor man to delight in, is evidence of the mastery of the man; as you hear it or sing it, in a formation other than a steelband, the combination of words and melody from Kitch makes it feel precisely that – pan music. Play the recording quietly when there is no one around to interrupt you, and listen carefully to that part of the song; you will immediately recognize the work of a tenor man in a steelband; Kitch has put it all there for us; which other calypsonian does it as well as he? Kitch is a master with those cascading notes, as if indeed he is himself a pan man writing pan music. And there is also the question of duplication: no other song-writer, in Trinidad or elsewhere, has come to the music bringing that dexterity with the cascade, and, while we’re at it, for the equally unique Kitchener quality of interesting and unusual rhymes – he will drop a rhyming word on you that you didn’t see coming; the unique side; mastery at play.

All these examples are up there on the web – Lord Kitchener, Norah Jones, Andrea Bocelli and Blakie – go up and take a listen and be reminded of the masters. Mind you, I can’t end without telling you that my favourite, if you force me to pick one, would be Kitchener’s Guitar Pan. It’s probably true that every song, no matter how popular it has become, has minute flaws in it, but if that is so then I cannot find the flaw in Guitar Pan. For me, that is musical mastery, without question. Kitch is unwrapping steelband construction for us, singing the notes as a panman would play them, and doing all that while also managing to bring us this musical labyrinth we all recognize from hearing the music on the road, and the imaginative rhymes. Ultimately, that is what the master musician does: he/she goes to the bands where they play, draws on that experience, and then comes back to us with a composition that replicates the form in such a way that we immediately recognize what we hear – it is the genuine article coming at us, in different words and different notes, and stirring within us, the sheer joy of good music well played. The examples are around; don’t take on too much the lamentations about “good music is dead”. Okay, you may have to do some digging to find it, but the rewards are great. Go to the web and listen to Guitar Pan. My writing may not make it clear, but listening to that music will. Lord Kitchener, definitely one of the masters.