Today’s column expands further on the reasoning behind the Guyana’s Petroleum Road Map’s finding that there is not sound economic reasoning behind calls to establish a state-owned oil refinery to process (and thereby add value) to its crude oil production at this stage of development of the country’s coming petroleum industry. As posited last week, such calls emanate from an autarkic economic paradigm. This paradigm argues to the effect that Guyana’s path for autonomous sustainable development requires the State (Government of Guyana, GoG), to pursue a “line of march” which ensures “Guyana produces all it can produce”. To do so it must, therefore, constrain (legally, administratively, and fiscally) “foreign, ownership, control of decision-making, and management” of its evolving oil and gas sector.

I had also in last week’s column indicated the developmental weaknesses of autarky, given that, particularly for Guyana, the reality is the country is too small and, therefore, not ever likely to become a consumer of all or even most of its potential processed crude oil production. More importantly, in that column, I had further pointed to the truism: “no two oil refineries are the same”. This truism is clearly evident in the data showing the number, output sizes and distribution of oil refineries, worldwide. Indeed, in concluding that column I had indicated this truism applies not only to the various sizes of refineries, worldwide but the variation also in oil refinery capabilities.

Oil Refinery Capability

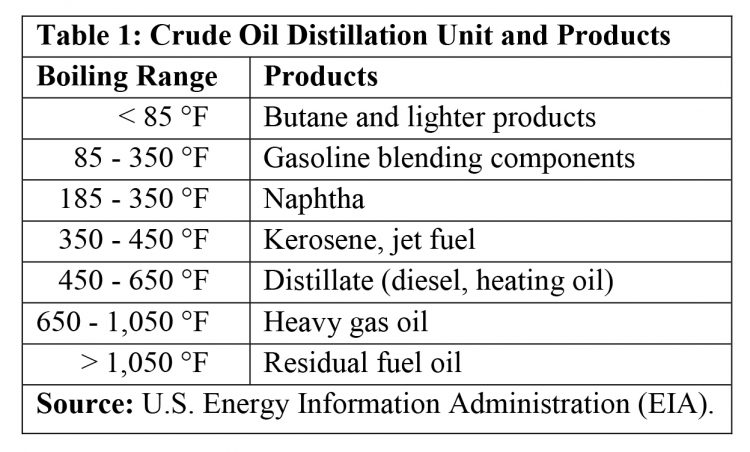

Oil refinery capability refers to the petroleum products which are produced from crude oil. The basic requirement of all oil refineries is a distillation column. Typically, this separates the crude oil into different petroleum products, based on their differing boiling points. The distillation column is combined with secondary processing units. The information in Table 1 shows the varying boiling points for a sample of crude oil and its product derivatives.

In my earlier columns I had also introduced readers to the standard industry-wide indicator of the level of capability of any oil refinery and, therefore, the rationale behind the truism: “no two oil refineries are the same”.

Empirics: Nelson Complexity Index

The Nelson Complexity Index measures oil refining capability and complexity by the level of secondary conversion capacity there is in the refinery, after taking into account the cost of each major type of refinery equipment. For the Index, the distillation column is given a value of 1 and the other units in the refinery are then assigned values on the basis of their conversion capability and their cost relative to the distillation column, which is valued at 1. The larger, therefore, the Nelson Index, the more complex is the refinery. And the more complex is the refinery, the more capable it is of producing higher valued products. And, correspondingly, the more costly they are to build and maintain.

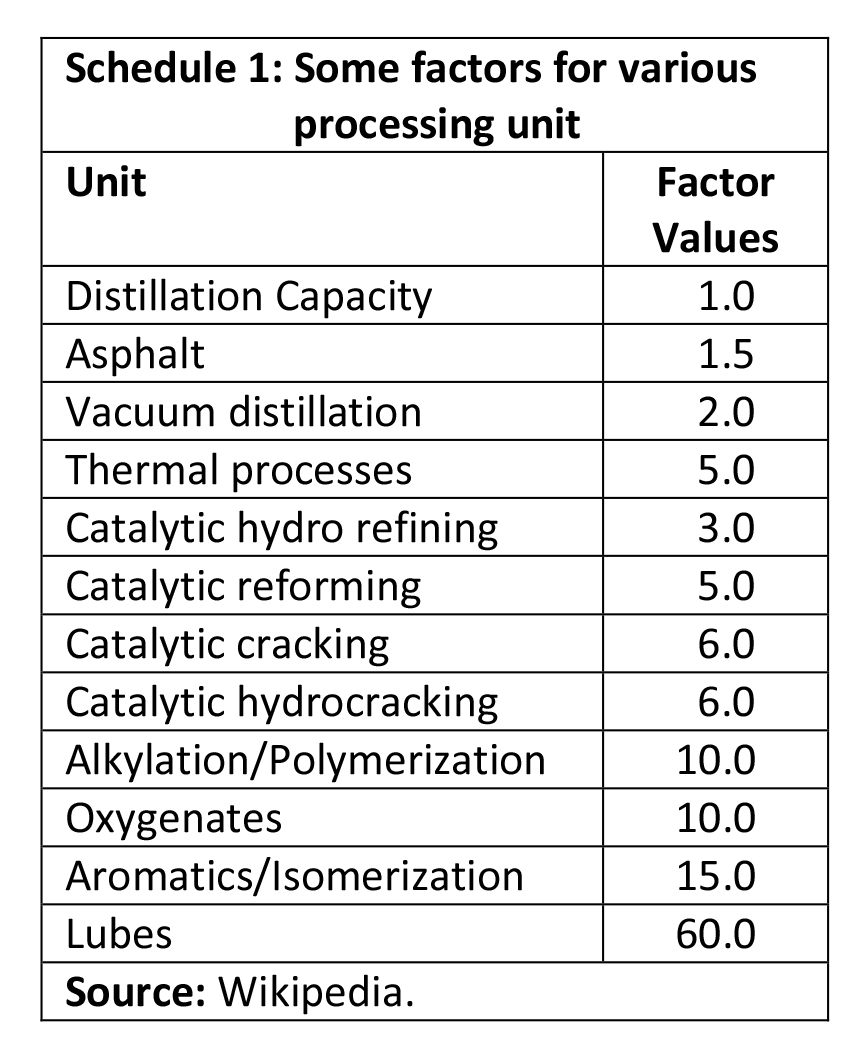

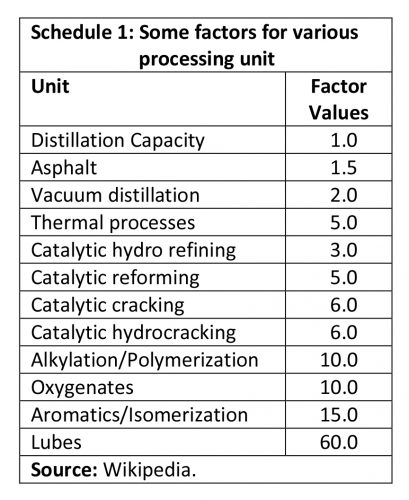

Typical complexity factors are shown in Schedule 1. Two decades ago, back in the 2000s, the global value of this Index was 5.9

Schedule 1 provides a guide as to the “factors” allotted to the various levels of capability in a typical refinery. I believe it is worth noting that the Nelson Complexity Index is more carefully described as an effort to quantify the sophistication (technological and otherwise) of a refinery, along with its capital intensity. Complexity, as used in the industry, classifies refineries hierarchically, and estimates refinery construction costs.

Proposals for GoG Oil Refinery

Proposals for a GoG-owned oil refinery appear to have an upper size in mind of between 100,000 barrels of oil refined per day (b/d) to 150,000 b/d. Based on current terminology, this is considered a small crude oil refinery. The focus of several proposals circulating in the media from private groups, seeking GoG assistance and/or joint venture with Government, seems to be for modular mini-oil refineries. Worldwide, such refineries have become an important segment of the petroleum refining industry. This is due to their flexibility, adaptability, lower capital cost and “off-the-shelf delivery” possibilities.

As was indicated in earlier columns (2017), these refineries are often pre-fabricated in factories and delivered to the sites from which they are expected to operate. Modular refineries can range from 500 b/d upwards to approximate the size of a small refinery.

While some private proposals were widely disseminated in 2017/2018, when I had first addressed this topic of a local oil refinery, in 2019, on the eve of First Oil, these proposals have very much disappeared from the media. The GoG’s Guyana Refinery Study, prepared for the Ministry of Natural Resources by Hartree Partnership LP in May 2017, which was released as a draft, remains the only publicly available GoG document on the topic.

Based on empirical evidence, energy economists posit the overall viable/sustainable economics of oil refineries are mainly a function of four variables; namely: 1) the type of crude oil, which it refines (the primary input into the process); 2) the complexity of the refinery; 3) the type of products produced; and 4) the prices of crude and the products it refines. This formulation applies to modular as well as conventional refineries. It is noteworthy that, configuration of modular mini-refineries, however, is not suitable for some refined products (for example lubricating oils, waxes and asphalt).

Conclusion

Going forward, my intention is to refer briefly to the findings of the GoG feasibility study on a state-owned oil refinery as well as private sector proposals (for mainly mini refineries) in the coming columns. Next week therefore, I continue the discussion and will conclude this topic in the Road Map, by indicating my recommended decision rules for guidance of the GoG on investment in an oil refinery.