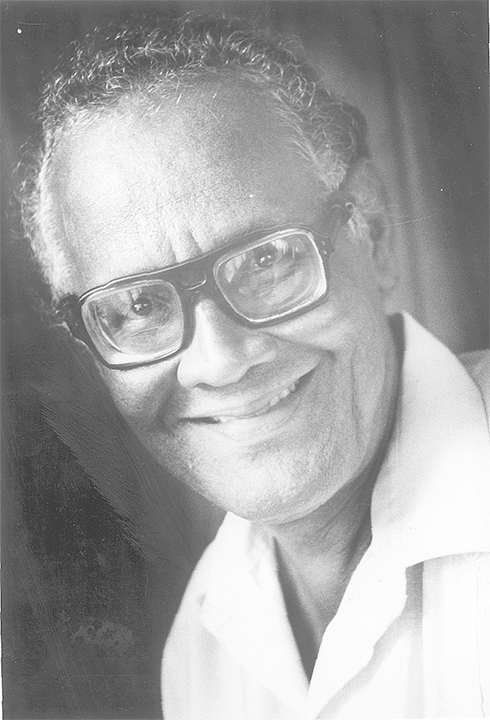

On the anniversary of Martin Carter’s passing Gemma Robinson is inspired by award-winning poet Vahni Capildeo to look at Carter’s work and the art of beginning.

What sparks poetry? This is the question that Poetry Daily poses to contemporary poets every week. The editorial team of this contemporary anthology asks a poet to reflect on a poem that ‘led them down the path to becoming a poet’. Recently, Vahni Capildeo, the Trinidadian Scottish poet, answered this question with Martin Carter’s ‘This Is The Dark Time My Love’.

Capildeo’s reading of Carter’s work is longstanding and multifaceted. In the poem ‘Hazardous Shelves, Deep Waters’ (from Undraining Sea (2009)), Carter’s words float on the page – part of a body of quotations from writers spanning different places and times to ‘show how one “sea” of voices rolls from an actual set of shelves or in memory’. Carter’s line ‘And what in dreams we do in life we attempt’ ends the poem, weighing our knowledge of the limitless actions of our dreams against life’s series of risks and challenges. In Capildeo’s ‘“sea” of voices,’ Carter emerges as a poet to help us test our actions and attempts, in life and word.

How fitting then that Capildeo in this autobiographical reflection on ‘This Is The Dark Time My Love’ frames Carter for us as a poet who helped them to begin a life of poetry. And true to the artistic complexities of both these authors, the apparently simple act of beginning turns out not to be so simple after all. Capildeo’s first encounters with Carter’s work are instructively blurred, created in part by the ‘canonical’ presence of Carter for a young reader born in Trinidad in 1973: ‘He is one of those who comes into the world of the imagination so soon—who can remember whether they first heard someone read out his verses or first puzzled them out for themselves on a scantly-printed page?’

Capildeo’s beginnings with Carter’s work are also focused on recognition and association. Taking the red flowers and brown beetles of the famous opening verse, Capildeo focuses on the ‘plain language’ and captures a youthful reading of these lines:

This is the dark time, my love,

All round the land brown beetles crawl about.

The shining sun is hidden in the sky

Red flowers bend their heads in awful sorrow.

Reading a poem here is all about questions and identification. Capildeo writes: ‘Red flowers: flamboyant, tulip tree, hibiscus, bougainvillea, ixora, roses, begonia, salvia…yes, there were a lot of those. (What did they have to do with “sorrow?”)’ From Trinidad, family bookshelves and the natural environment form a bridge from Capildeo to Carter’s words, forged in the specific struggles of anticolonial Guyana.

Then there is another recognition. The Jamaat-al-Muslimeen coup attempt in 1990 in Trinidad returns the teenage Capildeo to Carter’s poem and now the imagery begins to make another kind of sense: ‘Nor were red flowers only flowers. They would spring and spring. Sorrow does, and fire and blood, and struggle…’. The poem’s plain language allows its meanings to be reshaped by new readers from new experiences of ‘dark times’. Capildeo links this renewed personal recognition of the poem with the practice of becoming a poet: ‘How does it work, to start writing poetry? Isn’t the process start-stop-start by nature? … Like falling in love, there is another “first” time, and—lightning flash—another’.

Being open to starting, stopping and starting again are the characteristics of us as readers and writers. In Capildeo’s most recent collection, Skin Can Hold, ‘Astronomer of Freedom’ documents how Carter’s poem, ‘I Am No Soldier,’ inspired the creation of ‘multivocal performance texts’. Selected words from Carter’s poem are mesmerizingly opened out: recalibrated and suspended on the page as ‘syntax poems’, performed in call and response, transformed into dance, and incorporated into a parody of the colonial classroom. Carter’s twinned attention to falling and rising comrades encourages Capildeo to make a theatre of ‘intimate camaraderie’. It begins with Carter’s 1950s poem of international solidarities, which is then rearranged for multiple voices and bodies in motion:

comrade I shall arise

there are galaxies of happiness

there are… people… (there are)… brothers

Performed in Cambridge between 2014 and 2016, the result was a collaborative piece that immersed its audience in Carter’s call to literal and figurative comrades (in ‘Malaya’, Kenya, Korea, ‘comrade stargazer’, ‘Accabreh’s breed’, ‘life’s mapmaker’).

In ‘What Sparks Poetry’, Capildeo writes: ‘Carter’s work is emotionally revolutionary. Its moving detail and shapely music insist on empathy and formal poise in the face of a destructive, would-be overwhelming force.’ At the end of the piece Capildeo invites us all to begin writing, prompted by Carter’s ‘This Is The Dark Time My Love’. We are encouraged to focus on responding to the poem in the voice of the beloved, and to do this every day for two weeks. Capildeo models for us this ‘start-stop-start’ process, asking us to produce fourteen beginnings, then discard them, and write a new poem ‘on personal and political crises. What these crises might be is open for us to determine, but the hope is that Carter’s poem will let us begin to see what emotionally revolutionary poems we need for our own ‘dark times’.

A focus on beginnings, through Capildeo’s guidance, can show us how to create our own poetic voices. Attention to beginnings can also make us more attentive readers of Carter. I started to think more about where this word in its different forms appears in his work. Across decades of poetry, it is a key word and idea for Carter for articulating the personal and the political. It’s there in the 1954 essay, ‘The Lesson of August’ (first published in Thunder, the PPP’s magazine), where he focuses on emancipation from slavery and Indian independence as the difficult beginning of a new social order: ‘a future full of struggle’. It also appears in Carter’s earliest work, ‘To A Dead Slave’ (1951):

I sometimes notice how the day begins

first,

slight

and soft

and barely

in the East.

Here is a description of dawn, but why is it important to notice ‘how the day begins’? These lines evolve into a long, loose nineteen-line sentence giving shape to a land ‘full of day’. Carter’s inclusion of ‘sometimes’ could lead in many directions, but here it adds to the sense of how fragile and promising is our understanding of each new day as it begins. Capildeo’s phrase, ‘shapely music’ is useful here. The bare shape of the lines and the voicing of the sounds encourage us to slow down and appreciate the measured arrival of the day.

Carter then expands out from this beginning to describe a collectivity – a past/present/future ‘people whose great hands stretch everywhere’ – expressed within the structure of a day. They are a people who confront the struggle of their everyday lives, striving to make sense of it and change it. They ‘reason always how the slave should end / a day which rarely had a shaft of light’. Beginnings and endings work together. These poetic beginnings do not have the Biblical certainty of creation, but the religious echoes of origin stories give further shape to Carter’s work. He populates his world with questions about survival, about how to live a life where humans are part of a precarious mortal environment that also holds ‘the germinating spark’ of new beginnings.

Skip thirty years from ‘To a Dead Slave’ and we find Carter’s last explicit reference to beginnings in the poem ‘Faces’ from Poems of Affinity (1980):

Thus I began

to learn when I discovered why

every tree is as green as the reason

of the land on my holy hand

which keeps pointing forever inward,

but not beyond the veil of the lace

of tears of these faces.

Without trying to unravel the connected imagery here (holy land/hand; interiority/exterior faces; green reason), it seems important to notice that beginnings are tied to deliberative thinking, learning and discovery in Carter. More than that, expressing awareness of something specifically as a beginning seems to be part of how we engage our powers of understanding and action. ‘Now to begin the road’ he repeats in ‘Cartman of Dayclean’, opening out into bound and unbounded time and space. ‘New day must clean’ he asserts in ‘Not Hands Like Mine’. ‘In the beginning, if there was’ he wonders in ‘Even as the Ants Are’.

By the time he wrote ‘Faces,’ Carter had developed a complex web of empathetic reasoning and knowledge. Consider its grammar (how do we read the lines from ‘Faces’ as a sentence?) and its concepts (how do we grasp the imagery of the poem?). His work is empathetic because even at its most demanding Carter’s poetry is seeking to make sense of fellow feeling, just as he was in his earliest poetry. Even this later work can be read as ‘emotionally revolutionary’. These words combine to pinpoint the special charge of Carter’s work. Certainly, his interest in beginnings has a compelling foundation in political struggle – the search and call for new dawns, new days – which is always responding to ‘destructive, would-be overwhelming force’. The combined resistance and demand for change in his work is also rooted in a lyric sensibility. His are poems of emotion, love, individual feeling, but they do not stop at romance. In ‘This Is The Dark Time My Love’ and throughout his work he embraces a wide connected environment of the human and non-human. Capildeo notes in ‘Astronomer of Freedom’ that Carter writes in the ‘I that can be we’.

The word ‘begin’ has its roots in an old German word meaning to ‘cut open’ or ‘open up’. So the etymology gets us thinking about a spatial image, while our current use of the word is focused on time. Capildeo, who used to work for the Oxford English Dictionary, might find these different meanings productive:

But who is Martin Carter as a matter of inspiration, now? He is one of those poets you turn to throughout a lifetime. Watch the ruptures in experience he writes about. Feel anew the ruptures in your experience. Re-begin the process of poetry. Each time is another first.

Capildeo’s phrase, ‘ruptures in experience’, is an important idea for Carter’s beginnings. In ‘This Is The Dark Time My Love’, facing and articulating ruptures becomes Carter’s way of ‘opening up’ experience. The violence, hurt or estrangements (cracks, splits, shatterings, breaches, tearings, divisions) implied by Capildeo’s phrase must be squarely faced. They are forces that can make us begin our actions. For what purpose? To begin to understand and then act to make a change. To lay bare what has been hidden. To examine that which we thought we knew. To see something for the first time, or as if for the first time.

Sometimes Carter’s ruptures in experience are not based in violence or coercion, but are the everyday breaks in our lives. These are no less significant or extraordinary. Consider the opening lines of ‘Cuyuni,’ a poem written in 1972:

Inside my listening sleep

a roar of water on stubborn rock

was the whisper of blood in the womb of my mother.

And when I awoke

I began listening again.

Carter’s lines remind us of the constancy of Capildeo’s start-stop-start rhythm. In another poem Carter would reimagine these beginnings and endings as part of something limitless, perpetual and hopeful: ‘I romp this endless moment world / returning, reshaping, rejoicing’.

Capildeo and Carter share an intelligence for linguistic innovation and connection. They stretch language, working between plain and esoteric vocabularies. When they encourage us to pay attention to beginnings, a world of associations and affinities opens up. Their combined work is an invitation to join their reshaping of words and worlds. As reader, writer and performer, Capildeo shows us how to open ourselves to Carter’s poetry. Capildeo urges us to turn to Carter throughout a lifetime: ‘each time is another first’. In the company of Carter and Capildeo, poetry can be a guide, or compass, a conversation, a riddle, or a spark.

Gemma Robinson is the editor of University of Hunger: the Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe).

Vahni Capildeo is the author of seven books and four pamphlets, most recently Measures of Expatriation (winner of the Forward Poetry Prize), Venus as a Bear and Skin Can Hold (Carcanet).