UNDP Resident Representative

At a recent rally held in Vreed-en-Hoop, the President declared that he and his Cabinet would remain in position and the Government would continue to function as normal until the entire judicial review process to challenge the Chief Justice’s ruling is exhausted to the fullest. This appears inconsistent with the earlier statement made following the 10 January 2019 meeting with the Opposition Leader that the Government would respect the ruling of the Speaker of the National Assembly while at the same time seek a judicial review of his ruling. We interpret the latter statement to mean that the Administration would adhere to the requirement to hold elections by 21 March 2019 (or such later date as approved by two-thirds of votes of the members of the National Assembly), unless within this timeframe the Court rules that the no confidence vote is invalid.

The President has now chosen to ignore not only Articles 106(6) and 106(7) requiring him and his Cabinet to resign and to hold elections within three months but also the decision of the Chief Justice to disallow an application for a stay of her decision and a conservatory order for the Government to remain in office.

Today’s article looks at another controversial issue that surfaced recently. It relates to the Minister of Finance’s decision to increase the thresholds for Requests for Quotations (RFQs) and restricted tendering.

Notification by the NPTAB

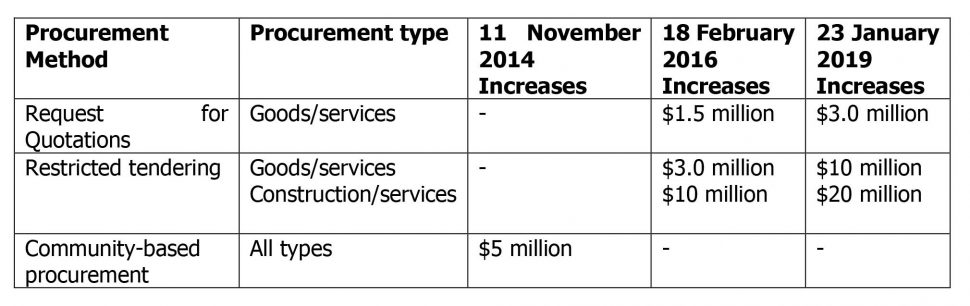

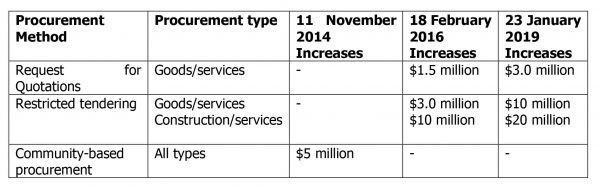

By letter dated 4 February 2019, the National Procurement and Tender Administration Board (NPTAB) notified heads of budget agencies and corporations of the increases in the threshold limits for RFQs and restricted tendering based on an Order dated 23 January 2019 issued by the Minister. This is the third time in the last four years that procurement threshold limits were increased to reflect changing market conditions and to maintain efficiencies in the procurement process, as shown below:

Requests for Quotations

In accordance with Section 27 of the Procurement Act, a procuring entity may engage in procurement by means of an RFQ where the estimated value of the procurement contract does not exceed the amount set out in the Regulations. Other procedures to be followed before the contract is awarded include: (i) obtaining and compare quotations from as many qualified suppliers or contractors, but not fewer than three; (ii) making dedicated efforts to check prices on the Internet to ensure the reasonableness of quoted prices; and (iii) publishing the price of the most recent procurement at least once a quarter in a newspaper of national circulation.

Restricted Tendering

Section 26 of the Act permits the use of the restricted tendering method of procurement when: (i) the goods, construction or services are of a highly complex or specialized nature and are available only from a limited number of suppliers or contractors; and (ii) the estimated cost of the procurement is below the threshold set out in the Regulations. Only qualified suppliers or contractors are invited submit tenders, and all other steps and requirements applicable to open tendering are to be followed. These include:

(a) Notification to all such suppliers and contractors of the proposed procurement;

(b) Adherence to the procedures relating to the opening of tenders;

(c) Appointment of an evaluation committee to assess the tenders and to identify

the lowest evaluated bid; and

(d) Request to the Cabinet for its offer of ‘no objection’ to contracts in excess of $15

million.

As can be noted, the only difference between open tendering and restricted tendering is that in the case of the latter, there is no public advertisement every time a procurement is to be made. Rather, all suppliers and contractors shown in the list of restricted tenderers are contacted and requested to submit tenders. This list is prepared from the register of qualified suppliers and contractors, compiled following advertisement to prequalify, usually at the beginning of each year. It makes little sense for a procuring entity to advertise publicly whenever a procurement is initiated when only, say four or five, suppliers or contractors would be bidding by virtue of the complex and specialized nature of the procurement, hence the rationale for restricted tendering.

Procurement for Remote Communities

By Section 29 of the Act, in remote areas of the country where it is not possible for procurement to be undertaken using competitive bidding procedures, procurement below the threshold limit set by the Regulations can be undertaken using either the single source method or through community participation organisations. The last increase in the threshold limit for community-based procurement was approved by the Cabinet on 11 November 2014, the day after Parliament was prorogued. In addition, the increase was made applicable to Neighbourhood Democratic Councils, most of which are located on the coast where competitive bidding procedures could easily be followed.

Were the recent increases in the threshold limits illegal?

It has been argued that the Minister has acted illegally since only the Cabinet can approve of increases in threshold limits for public procurement. Section 54(1) of Procurement Act has been cited in support of the argument:

The Cabinet shall have the right to review all procurements the value of which exceeds fifteen million Guyana dollars. The Cabinet shall conduct its review on the basis of a streamlined tender evaluation report to be adopted by the authority mentioned in Section 17(2). The Cabinet, and, upon its establishment, the Procurement Commission, shall review annually the Cabinet’s threshold for review of procurements, with the objective of increasing that threshold over time so as to promote the goal of progressively phasing out Cabinet involvement and decentralizing the procurement process.

The above section refers clearly to only the Cabinet’s offer of ‘no objection’ to the award of contracts in excess of $15 million and has nothing to do with setting threshold limits and the procedures to be followed for the various methods of procurement. The authority mentioned in Section 17(2) refers to the NPTAB performing the functions of the Public Procurement Commission (PPC) until such time that the latter is activated through the appointment of its members.

It will be recalled that the 2001 constitutional amendments provide for, among others, the establishment of the PPC with the following objective:

To monitor public procurement and the procedures therefor in order to ensure that the procurement of goods, services and execution of works are conducted in a fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost effective manner according to law and such policy guidelines as may be determined by the National Assembly [emphasis added].

At the time when the Procurement Act was passed in 2003, the PPC had not yet been established, and it was mainly for this reason also that the second sentence of Section 54(1) was inserted in the Act.

By Article 212AA(e), the PPC can approve of procedures for procurement and make recommendations for any modifications thereof. While this suggests some involvement of the PPC, it should not be over-emphasised that the PPC is an oversight body and cannot get involved in operational matters, such as approving increases in procurement threshold limits. That responsibility vests with the Minister by Section 61 of the Procurement Act which provides for the Minister, on the advice of NPTAB, to make regulations that may be necessary for the administration of the Act. Thresholds limits for the various forms of procurement must be reflected in the Regulations as provided for Section 26 of the Act, and it is only the Minister who can make Regulations, not the PPC. The Minister has delegated authority from Parliament by virtue of the fact that the Procurement Regulations are subsidiary legislation made under the Procurement Act.

We are fully aware of the supremacy of the Constitution and that where there is a conflict between any legislation and the Constitution, the latter takes presence. However, we are convinced that no such conflict exists as it relates to the setting of threshold limits for the various forms of procurement. Over the years, there have been numerous increases in these limits. Prior to 2003, it was Cabinet that would approve of such increases since there was no legislation in place for public procurement. With the passing of the Procurement Act, that responsibility is vested in the Minister who exercises it via the issuance of an Order. One would, however, expect that the Minister would first seek the blessing of the Cabinet before an Order is issued, as was done in the case of the 2014 increase.

If the latest Order issued by the Minister is illegal, then all previous Orders should be so deemed, including the Order issued by the former Minister following the Cabinet’s approval of the increase in the threshold limit for community-based procurement the day after Parliament was prorogued!

In view of the foregoing, we maintain our previously stated position as reflected in the Stabroek News article of 8 February 2019 that there is no contravention of the provisions of the Procurement Act as it relates to the issuing of the Order of 29 January 2019 for the increases in the thresholds limits for RFQs and restricted tendering.

Since the Procurement Regulations are subsidiary legislation, perhaps the more pertinent question is the timing of the increases in the light of the 21 December 2018 vote of no confidence. In a previous column, we had stated that during the period between the passing of the vote of no confidence and the date for the holding of fresh elections, no new contracts should be entered into, no new legislation should be passed, and no new capital expenditure should be initiated. In the same vein, one could also question the timing of the 11 November 2014 increase at a time when Parliament was prorogued.

A final note. The PPC was established in October 2017. Since then there has been no evidence of any effort being made to progressively phase out the involvement of the Cabinet in the procurement process or to eliminate its role, as provided for by Section 54(6) of the Act. That section states that ‘Cabinet’s involvement under this section shall cease upon the constitution of the Public Procurement Commission except in relation to those matters referred to in subsection (1) which are pending’. This is a major disappointment for those who fought so hard in advocating for the reform of our public procurement systems to ensure greater competitiveness, transparency, cost-effectiveness and to minimize the extent to which corruption is perceived to exist in this area of government operations.