“The Old Man & the Gun” is, in theory, a cat-and-mouse game. Forrest Tucker continues a string of audacious bank robberies that confound the authorities for the brazenness of their deployment. John Hunt, a police detective, is particularly rankled by the casual charm of the mastermind and sets out to find the criminal in question. And so, Tucker continues his robberies as Hunt closes in on him. But, “The Old Man & the Gun” is more than a cops-and-robbers tale. The very best thing about Lowery’s film is the inexplicable way it becomes something altogether different from what it is. For, it is neither the jokey premise of an elderly robber, nor is it the potential angsty police tale. Instead, it is a warm but affecting story of two lives searching for meaning.

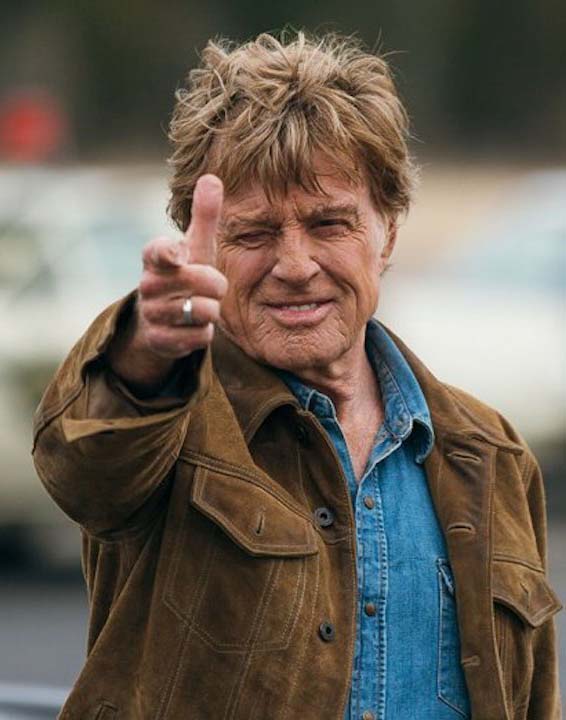

It’s no accident that we meet Detective John Hunt on his fortieth birthday. He seems despondent in his police job. His life seems marked by an idle restlessness. When his paths cross with the itinerant Tucker on a robbery, the chance to do something in the form of catching him injects Hunt’s professional life with a purposefulness that feels kinetic. Casey Affleck, starring in his third feature with Lowery, plays Hunt with an undertone of melancholy that’s bathed in a practicality. Whereas Redford, as the charming Forrest Tucker, is like a man out of a fable – overwhelmingly charming, fanciful and almost paradoxical in the ways he seems beyond human. Lowery’s greatest accomplishment in the film is imbuing both men with compelling auras. Instead of siding with either, we become content to watch them dance around each other until the inevitable scene where they do meet that’s rewardingly bizarre and compelling for how unexpected it is.

For, as different as the two men are, they both understand the restlessness that comes with a live that’s unlived. There’s a restless despondency that can attack one during adulthood, and both men play out this despondency on opposite sides of the law. When Jackson C. Frank’s song, “Blues Run the Game” appears to punctuate an important, disastrous, job towards the end of the film, the song cue delivers an aural thesis of the way this film operates. Frank’s folk song is an expert sleight-of-hand. It features a comforting, folksy melody that hides a sad, yearning unhappiness. It’s that yearning for a life that’s so familiar and important for this story. And it’s an aesthetic that marks “The Old Man & the Gun.”

Late in the film, a character eloquently sums up Tucker’s ideology. “I sat down with him once and I said, “Surely there’s an easier way to make a living.” And he looked at me and said, “I’m not talking about making a living. I’m just talking about living.” It’s an unsubtle point, but one which the film depends on in order to coalesce. What does it really mean to live one’s life? And what are the costs we are willing to take to do so? I would be lying if I said that “The Old Man & the Gun” feels especially apropos of our time. The film is from another era. It takes place in the very early eighties and recalls visual aesthetics of the late seventies. There’s a relaxedness to its developments that feels antithetical to 21st century cinema and yet I keep returning to that yearning for living. It feels emphatically relevant.

Lowery is at the height of his abilities here, using his gifts of subversion to confound us through charm. The aesthetic work on show here subverts the sharpness of the script, beguiling us with gentle warmth that momentarily hides the dark underbelly of the lives these men lead. So that the blues they are both running from sneak up on us when we least expect it. Tucker keeps robbing banks because he wants to feel alive. Hunt needs to find Tucker to provide his working life with some context. The film complicates this by allowing both men rich, romantic lives with their respective spouses, forcing us to realise that even personal fulfilment can be no match for the need to do something important, on his own, that these men feel. It softly suggests an intriguing tale of masculinity in crisis. When it’s all over, “The Old Man & the Gun” goes down very easy. It’s a lithe 90-minute romp, and it leaves us smiling. But this is no bauble of a film. Its softness only explicates its value. For surely, we’re all living lives that are marked by some kind of blues, the question is what we plan to do to outrun those blues.

“The Old Man & the Gun” is available to rent or purchase on iTunes, GooglePlay, Vudu, YouTube and AmazonPrime.