In this iteration that has come to fruition, our chief player is Oscar Isaac’s Santiago. He is a retired army man working as a private military advisor in Columbia to combat the scourge of drugs. A tip from an informant leads him to the whereabouts of a very rich and very dangerous drug-lord and what at first seems like a heroic quest to apprehend a criminal becomes a personal plan to line his own pockets. The love of money is not quite the root of all evil in “Triple Frontier” but it is the root of all chaos.

But, the film takes some time to set up those roots. The military angle is what defines much of the first act. As Santiago tracks down his former colleagues for assistance with his heist, the thread reverberating through their lives is the disillusionment of life after service. This is familiar territory for screenwriter Mark Boal. Boal is most famous for his Oscar-winning writing and producing on Kathryn Bigelow’s Iraq war film, “The Hurt Locker.” Bigelow, incidentally, was initially scheduled as the director for the film when the cast featured Tom Hanks and will Smith in 2011. And Boal’s interest in contemporary warfare seeps into the film, as it diverts between an occasional post-war character study and the high-octane action thriller it more often is.

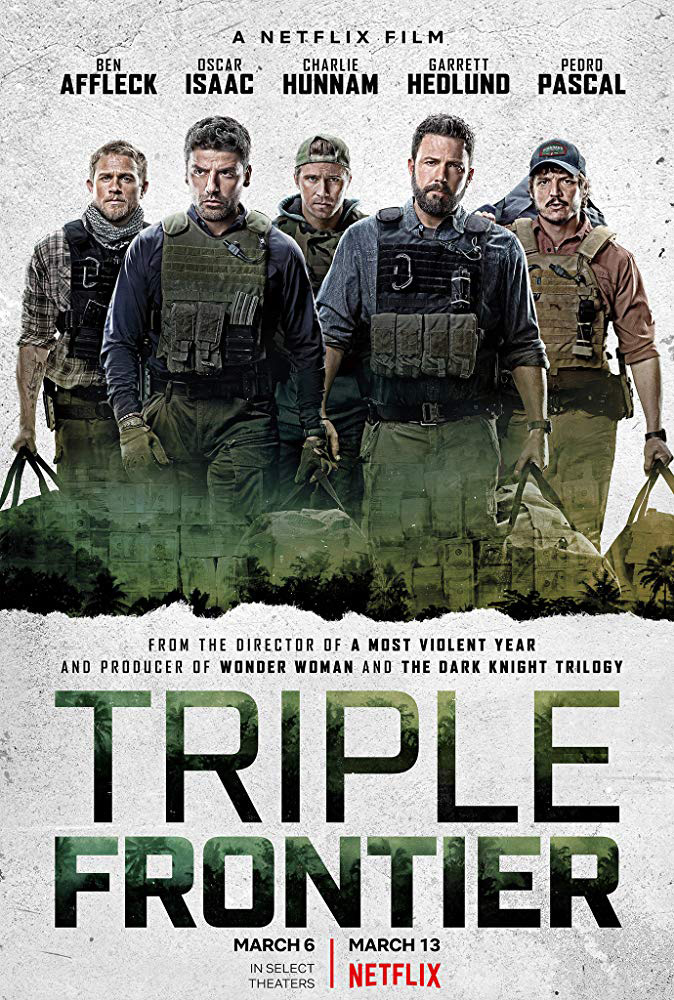

The set-up of the men’s relationship to the war in the 21st century is more schematic than anything though. These first scenes work more because of specificity in character formation and the intrigue of watching five actors of varying talents (Oscar Isaac, Ben Affleck, Charlie Hunnam, Pedro Pascal and Garrett Hedlund) shuffle around each other, each riffing on some version of 21st century masculinity. The roles themselves lack enough specificity to make the character studies work, but each of the five is having enough fun and doing enough to make the interactions work. Affleck, in particular, as the most despondent of the lot, is especially impressive. Meanwhile, Hedlund harnesses his usual propensity for explosive unpredictability into making the thinnest character of the five more intriguing than you expect. But no matter what Boal attempts, the film is not quite a character study.

Director J.C. Chandor is flexing his action muscles and there is an aspect of the drama that feels torn between lionising these jaded men and then taking them to task for their mercenary desires. Amidst that we are privy to some well executed action sequences, with the central heist unfolding with compelling precision that feels slightly too efficient at times. The film gets better later on when things go awry, but it’s really all grounded by the actors who have an undeniable chemistry that legitimises the film’s later discursions.

And, yet, the aggressively chaotic middle sections leave me wondering about the ethics and implications of neo-imperial America’s presence in Latin America. The cultural dynamics are, perhaps accidentally, shifted by the casting of Chilean-American Pascal and Guatemalan-American Isaac in two of the lead roles. But neither Boal’s writing nor Chandor’s direction takes these implications to any satisfying payoff. While film features some effete nods to the larger global situation it never cares to examine the larger potential for drama in the way that this region continues to be exploited by the United States. That South America’s landscape continues to persist in Hollywood as a nameless backdrop for senseless violence and drug-related crimes feels significant even if the film never examines it. The title of the film itself feels like a misnomer. It’s almost accidental that the film is set on that triple frontier of Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil.

There is a scene the middle with film when the five men make their getaway and crash into the lands of some indigenous people. It’s just as their plot is meandering out of control, and the brief sequence is as effective for the text as well as the subtext. It’s one of the few moments the film forces these American men to examine their intentions and the implications of their crimes. The subtext of these native people facing the scourge of foreigners feels incredibly potent. But the film must leave this indigenous land soon, and moves to its natural end with its eyes focussed firmly on America as its redemptive centre. But “Triple Frontier,” like the best and work of 21st century action films that flirt with international borders, is not interested in the geopolitical implications of its setting. Instead it simply wants us to observe our would-be-heroes-turned-anti-heroes struggling with their issues. And, in that way, the film is mostly effective. It held my attention for its two hour run-time and manages to eke out a surprisingly satisfying ending despite its digressions.

Triple Frontier is streaming on Netflix.