You really can’t put a price on representation. There is nothing quite like seeing shades of your life vividly represented in the media you consume. This representation is all the more compelling when it’s a rare occurrence. And just as significant when the mode of representation is in willowy wisps. This seemed especially potent to me as I watched the Jamaican revenge tale “Yardie” earlier this week. Guyana is miles removed from Jamaica and yet there is a relative homogeneity that comes with the Caribbean experience. And the crowd I watched it with, small as it was, seemed to pulsate with that knowledge. The sense of solidarity was thick throughout with a heady atmosphere of recognition – the crowds in the streets grooving to the reggae, the tenement yard living with the grandmothers who become the backbones of the family, and the mothers who migrate with their infants in search of a better life. The beats were familiar, even trite in some regards, and yet their incarnation in an emphatically Caribbean way emerged as most significant through it all. Even when the narrative could not keep itself afloat.

“Yardie” tells the story of Dennis Campbell (or D). As a young man, D watches his brother – a Rastafarian pacifist DJ, Jerry Dread – murdered in a foiled attempt to use the power of his music to satiate defuse a battle between two opposing gangs. D is traumatised by the killing and grows with a hardened heart, intent on avenging his brother’s death. Things come to a head when adult D, now working for a crime-lord, finds himself on the streets of London with a surprise chance to exorcise the ghosts from his pasts. This premise is rife with dramatic potential. And it is not quite fair to say that “Yardie” squanders this potential, and yet it’s surprising just how despite the possibility of so much dramatic import the end result feels so weightless. The film’s best moments are of darkened rooms and grinding bodies as seductive reggae rhythms seep through the atmosphere, and yet the occasional vividness of mood never makes for a wholly complete sense of place. Still, the film is not negligible. How could it be with so much at work beneath the surface?

The thing about much needed representation is that it can trick you into reading value into things which are more schematic than visceral. Like water for the man dying of thirst, the early scenes as immigrant D meanders through the streets of London feel like a salve to a generation making me think of Trinidadian Samuel Selvon’s seminal novel on the Windrush Generation, “The Lonely Londoners.” There’s nothing quite like that Caribbean solidarity and so it’s hard not to read the socio-political context into scenes like D’s stop at a shop in London littered with Caribbean flags, where poor immigrants make their way to make cheap international calls back to their homelands. There’s a post-colonial charm to watching the Caribbean identities adapt to a western effect or watching the way Jamaican culture is commoditised like an article of clothing for the Native Londoners to put on. But, much of this comes from what you bring to the film. Like the stories you read into a blank slate, rather than the stories you intuit from an evocative image.

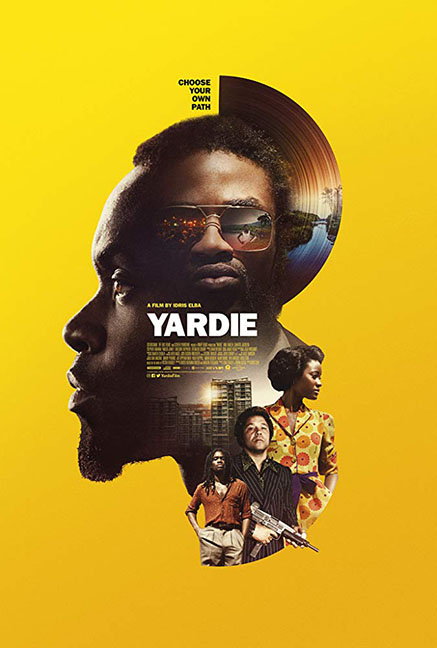

The film is notable as the directorial debut of English actor (of African heritage) Idris Elba. I wonder what drew Elba to the story, and then felt guilty for the potentially reductive way I wondered what a Caribbean person may have done different. “Yardie” means well, and is always entertaining even if it is not always effective. The film is felled by a penchant to tell more than show, manifested in an overhead narration that adds nothing. Kudos to Aml Ameen (a British actor born to Jamaican parents) that he manages to make D interesting and compelling even when he seems more passively reactive to his story than he should be. He’s at his best opposite Shantol Jackson (a Jamaican actress, who emerges as the best in show) in the film’s domestic discursions, which end up achieving an emotional potency that is less present in the gangster plots. It’s a duality the film struggles with throughout. It feels uncertain whether to commit to being a crime-comedy or a sensitive family drama about loss and identity. When its climax comes, it feels too easy and too convenient but manages to be bolstered by the sheer force of effort that the actors are putting in.

“Yardie” opens in 1973. That was an important year for Jamaica, at least culturally. The classic Jamaican film “The Harder They Come,” which was released at the Venice Film Festival one year earlier, would be released in the US and become a breakthrough for reggae music in the west. The film would go on to be a watershed moment for Caribbean cinema. Strains of Jimmy Cliff’s song kept playing in my head as I watched “Yardie.” Not because it invokes or evokes the ghost of that film. Instead, because of the rarity of that sort of representation I could not help but think back to Cliff’s film and performance as a sort of spiritual brother. You really can’t put a price on representation, and in the absence of that representation “Yardie,” for all its issues, feels good enough. For now. A glimpse into a world that is rarely seen on the big screen in this way.

Hopefully in twenty years its existence is merely incidental and the Caribbean experience is rendered on screen in a more effective and thrilling ways. But, for now, it’s what we have.

“Yardie” is now playing at local theatres.