Dani’s anxiety is at stratospheric heights when the film opens as it is precipitated by a seemingly manipulative sister. This anxiety is not helped by her emotionally reticent boyfriend, Christian, whose taciturn countenance is more pronounced when put against the frailty of Dani’s anxiety. Their relationship woes are (very) briefly paused when Dani’s family tragedy strikes and in that wintry prologue we get the first striking tableau of the film.

As Dani lays prostrate across Christian’s knees, weeping with an emotional abandon that feels too private for us to observe, he sits still. He stares ahead at the camera, not at her, like a man trapped and unable to grapple with the emotional nakedness of Dani’s grief, uncertain how to reach out to this woman that needs more than he can give her. A tableau like this will follow later on but even before we get there, the moment goes on long enough to make us shudder with discomfort at this ill-matched pair. The tableau is, of course, a metaphor. At the heart of this relationship are two people on markedly dissimilar emotional planes. It is central to “Midsommar” even when it seems like it’s not.

Six months later, the two are still together. Inexplicably so. Christian and three of his university friends are taking a trip to Sweden for a pagan summer festival. Dani is invited more out of obligation than any earnest beseeching, but she tags along, needing some company in the recesses of her grief. The plan seems immediately bad. Christian’s friends resent this woman who has entrapped their friend in an emotionally stressful relationship, and Dani’s needs are clearly unmet in this perfunctory romance, especially in her grief-addled state. This is not the recipe for a good vacation. Add to this dynamic a Swedish cult and things get decidedly more troubling. So, as the four Americans and Pelle, the Swedish native, arrive at this idyllic commune, with no cell service or electricity, the audience is already meant to intuit that things won’t go well. For all the sunny bliss the group initially meets at the summer, we know that what happens after their arrival will not be as idyllic. Even if “Midsommar” were not a horror film, we know from the most casual knowledge of artistic conceits that the almost preternatural calm that is initially invoked at the commune will give way to something more sinister. And the film makes good on that, slowly and deliberately building tension until things reach deliriously unnerving heights of depravity.

The best thing about “Midsommar” is its precise stylistic focus. At its best, the film benefits from an incredibly stylised conceit that turns brightness into something awry. I am a sucker for a good sound design in films and “Midsommar” is incredibly specific about the way it deploys sound to dizzying effects. The first thing we hear in the film is the ringing of a phone that sounds immediately too loud. At first, I thought that there was something wrong with the cinema’s speakers until the film continued and I realised the sound is the film’s key to suggesting something just slightly off about this world. As far as cultivating mood goes, “Midsommar” has its focus in the right place. But mood is not all the film’s wants to evoke here.

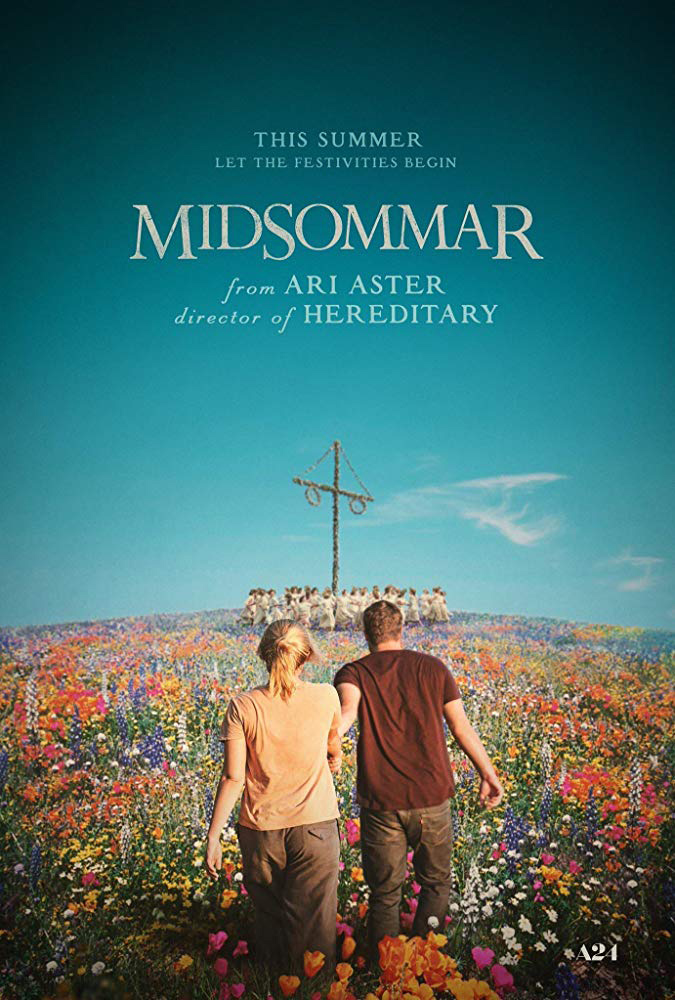

Ari Aster directed last year’s family horror “Hereditary,” a tense but unrewarding experience that felt too discursive for me to be invested in. In “Midsommar,” he ditches the chains of family for the chains of friendship and romance but his interest in grief persists. So, the film seems fractured in two. There is a moody, atonal, plotless film where we watch a cult slowly encroach on the visitors it’s hosting, and there’s another about a young woman coming to grips with the unrewarding relationship she is in. The trouble with “Midsommar” is that the first film is so much more emotionally and artistically certain than the second film, but the director depends on the second film to deliver the emotional punch that neither film really manages to make good on.

For all the nervous tics that are elicited from the sound and production design by the half-way point of the 147-minute “Midsommar” (and you feel each minute of the run-time), something had begun to nag about at me – the film’s own disinterest in the characters it was representing. Even when “Midsommar” makes good on isolated moments of impressive world-building, the film is punctured by a haziness that befalls the characters that inhabit this world. The haziness of their motivations is at first a question mark that the film seems intent on answering in time. Why are Christian and Dani together? Why has Pelle invited his friends here for this trip? What do the ambiguous sequences of the commune mean? What is it all for? In “Midsommar,” Aster repeats the elements that made “Hereditary” so frustrating to me – the film is all projection but fails to provide any depth to that projection. And that would not be an issue if the film didn’t seem to think it was projecting depth. Christian and Dani seemed destroyed by the lack of mutual empathy in their relationship, but Aster seems similarly confounded by his own inability to harness any empathy for the characters within the film.

Despite the effectively suffocating atmosphere sustained by the technical aspects, there is little in the narrative to provide anything resembling emotional catharsis. So, “Midsommar” leaves us to read importance into what little meaning we can grasp. There is the unsubtly named Christian, who will be the antagonist figure for this pagan cult. And, of course, as the film comes to its close, the thing that most affects our already emotionally fraught protagonist is her attachment to a loved one (get it: her last name is “ardor”). By the time the final shot of the film arrives, an increasingly malevolent smile as a short-hand for some sort of vengeance-as-catharsis idea that cannot hold, “Midsommar” seems to have abandoned any hopes of interrogating its characters’ motivations. Instead, it seems content to merely present a series of increasingly inexplicable disasters with disastrously ridiculous responses and an ambiguity betraying its own ambivalence. Last week, I mentioned in my review of “Ma” that the inexplicable behaviours of its characters made the film’s terribleness bearable through its inadvertent hilarity. In “Midsommar,” the behaviours that seem to betray the characters are more frustrating than amusing. Aster seems to pay little attention to the ethical, racial, or cultural implications of the characters’ actions but instead watches them run amok as a sort of game. It frustrates because “Midsommar” is a more proficient exercise with a vested interest in doing something challenging in parts, and there are sequences in the film that seem to be part of a good or even great film. But, Aster seems more interested in tableaus and set-pieces than people and their issues. And for the horror in “Midsommar” to work in the way the film intends, then the wake of tragedy must feel earned and potent. But, how can an audience feel anything close to tragedy when the creator observes the characters within his story with thinly veiled contempt?

“Midsommar” is currently playing at Caribbean Cinemas and MovieTowne Guyana.