L’Esperance is a farming community situated between Noitgadacht and Sans Souci along the Number One Canal Polder road. Today, with many of its early villagers having migrated or died, the village has no more than 50 residents with a third of its houses being unoccupied.

The name L’Esperance is of French origin and loosely translates to ‘hope’.

Sugarcane plants grow along the road at different parts of the village. Flowers reach beyond the fences brightening the area. Outside one house several fruits: soursop, bananas and pineapples were piled up awaiting a customer arriving from Rosignol, Berbice.

The residents farm in the backdam, some at the sides of their houses and others in the front of their yards and along the roadways.

Some of the early residents were the Sahais, Kallaks, Kanhais, Ramsakals, Ramjits, Gokuls, and the Persauds.

Nankumarie Persaud sat in her hammock keeping an eye out for customers visiting her shop. Everyone refers to her as ‘Aunty Daughter’. She was born and raised in the village; her mother was a native and her father from Golden Grove.

There was no road when she was younger. The main mode of transportation was boats along the canal. Her house, she recalled, was made of dew grass and manicole palms. Asked whether she would have made roofs and walls from these plants, Aunty Daughter said she did when she assisted in the making of the pens for her sheep and cows.

Her father, a farmer, reared cattle. The 69-year-old remembers getting up at four every morning and using a flambeau to see to make breakfast. When she was around nine years old Aunty Daughter was taught to cook. The first thing she learned to make was roti. Her mother after kneading and cooking the other rotis, left enough dough for her to make her little roti. She remembers being excited about such an opportunity. Once the sun was up, she hustled to do her other chores around the yard including to seeing to the ducks.

“I attended McGillivray School which went up to Form 4,” she said. “There was never Prep A and Prep B, only Lil ABC and Big ABC. There no nursery school either. I wrote two exams, the Preliminary Certificate and the College of Preceptors… There were higher levels of education children could have gone on to, but my parents had many of us to take care of, 14 of us. My father also said that his girl children weren’t going further than that. I was sixteen when I went to teach at a school at Hog Island. But my second brother, who was a policeman, was sent to fetch me after two months. When I moved back here, I kept a nursery school for children who were preparing to begin the primary level. Their parents paid a small fee. I did that for a few years until they opened the McGillivray Primary School. I was upset that I couldn’t further my education or was allowed to work but I didn’t make a fuss about it. In them days you had to please your parents; there was nothing you could do about it. Long years ago, you listened to your parents. You don’t go against them.”

The family, she noted, had too many cattle on their land to plant there and would travel to the Number One Canal Conservancy where they would head into the savannahs to farm. They planted pineapples and cash crops.

Not having had the chance to study and work as she would have liked, Aunty Daughter said she stressed the importance of education to her three children. “I would like to see the youths them develop themselves and be somebody in society. The people responsible for this would be the parents mostly. The child might not be keen on education because they don’t understand the importance of it but you as the parent who understand need to push them to educate themselves and to develop themselves. A vocational centre in the area will help those who are not academically inclined. They can learn a skill at least.

“Children today are much different from long ago. They lack courtesy. What they do know about though is the phone. The poorest child can get a phone. Parents don’t [converse] with children like before anymore. Long ago parents sit with you and talk. When you do something wrong, they scold you. There was time for books, time for chores and time for listening to the radio; there was no TV. We even had a time to get our homework done. Because we depended on the flambeau lamp, we were expected to get all our homework done before night,” Aunty Daughter shared.

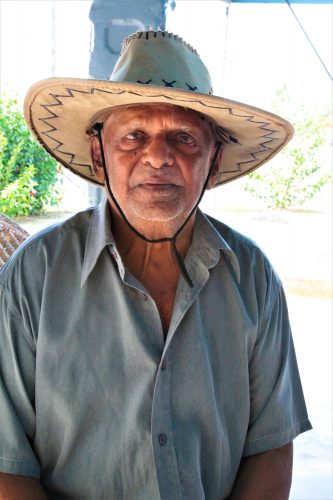

Eighty-six-year-old Dharamdeo Singh better known as ‘Buddy Bai’ is said to be the oldest resident in the village. He was born in Soesdyke, a few villages away.

Singh said he moved to the village some years after marrying his wife. Moving was a difficult time for him. He was 18 years old and his mother, who was sick at the time, insisted that he find someone to marry. An older friend of his made finding Singh’s bride his quest and not very long after he found him a young girl who was 14 years old. The two were married and for the next four years they lived with Singh’s parents.

Getting emotional, Singh recalled that his mother finally insisted that he go to live on his own with wife. He said he asked her what he had done wrong that led her asking him to do that and she explained that he had done nothing wrong, but it was time for them to live by themselves.

“They bought us a property. I didn’t know they buy us a place until after they buy it,” he said.

After living in L’Esperance for some time, Singh got a job with the National Drainage and Irrigation Authority (NDIA) and was provided one of the staff houses to live in. The couple moved with their children to live in La Grange. Then during the outbreak of racial disturbances in 1964, Singh’s wife moved back to L’Esperance with their children. He recalled family members pleading with him to move back to his home, but a number of his closest friends of African descent insisted that he stay on, promising him that they would protect him if necessary; it never became necessary.

He worked for 18 years with the NDIA and then at the behest of his wife to take up farming he left his job and returned home.

Farming, he said, turned out to be the best thing that happened to him. “My wife went to sell in Stabroek Market six days a week,” he said. On Thursdays he accompanied her since on this day vendors from Berbice would turn up to buy in bulk.

“We sold cassava, plantain, pineapple, mamey, mango, tangerine and orange,” he continued. “By half past seven in the morning my wife used to be back home because the produce was selling really good. We sold cassava for $1 a pound. Pineapples were expensive and we sold them for $600 a dozen. We had to take on labourers to work with us. After taking out our expenses and paying our labourers we still had a good lot to save which my mother kept for us. My mother told me to save and migrate and buy properties. I invested in the properties and bought for five of my six children. The house I’m living in will go to the son I didn’t buy property for. His wife died when their two children were very little. They can’t remember her. I raised them; they call me daddy.”

He recalled not knowing how to comb his granddaughter’s hair and taking her to the salon to have her hair cut to shoulder length. By the third salon visit, his granddaughter requested that he didn’t have her cut her hair again and he never took her back. Today both his grandson and granddaughter have graduated from the Government Technical Institute and hold certificates in General Administration and Data Operations respectively. They are currently awaiting replies to job applications that they sent out.

Singh, who grew up in a strict Hindu home, attended the Catholic school that was once situated in Nooitgedacht. Upon writing his school-leaving examination and passing Singh was asked to teach the young the children at the school. Three months later, his headmaster told him to go to church one Sunday dressed properly to be baptized. Had he done this, he said, he would have been awarded a scholarship to study law.

When he related to his mother what the headmaster had said, she grew quiet and whispered it to his father when he got home from work. His father, in a rage, prohibited him from being converted to Christianity. Prior to being told to be baptized, Singh had secretly studied for the Junior Cambridge Exams not wanting to upset his father; he passed the examination. Not getting the scholarship prevented him from pursuing his dreams as a lawyer. Years later, Singh found himself at La Grange Magistrate’s Court every Tuesday morning, sitting in the pews looking on. He would return home after that to share his knowledge of the cases with his wife.

He has had a full life, he said. Today at his age he doesn’t suffer from any illnesses and can take care of himself, as well as do a few chores including cooking which he did earlier in the day. But he quickly added that he hardly ever has to since his granddaughter helps to take care of him. His daughter and other children live close by also. He loves to read and still tries to do a bit of farming.

Singh pointed out a patch of calaloo growing nicely in the front of his yard, adding that he was responsible for the karilla growing along the fence also. His sons have since taken over his 15-acre farm on which they grow citrus.

Sabina Beigh hails from Cane Grove in Mahaica. She moved to the village five years ago to live with her partner, with whom she shares a four-year-old son. “Cane Grove is brighter,” she said. “The houses are bigger and the population [larger].”

But the young woman said that adjusting to a quieter atmosphere was not hard for her as she worked in Georgetown and was always too busy to miss home. When she left home in the morning, she did not get back until it was dark. The biggest challenge for her then was transportation. She had a special bus that she caught daily and left home at 6.30 every morning to make it to work for eight. The traffic at the Demerara Harbour Bridge, the woman said, was so terrible that she always barely made it in time. Getting transportation on holidays was the worst and often when the family wanted to visit family and friends, they were forced to stay at home instead. Today, however, transportation is not much of an issue, though at off-peak hours the wait is longer.

The family kept a kitchen garden until recently. Beigh said the crops were not growing as expected and she cleared them away. She visits the Bagotville market situated at Bagotville/La Grange whenever she needs to get her supply of fruits and vegetables. She rears her own meat birds and relies on the two mobile shops that traverse the village four times a week.