This essay draws from ongoing academic work between myself and a talented young financial analyst, Mr. Joel Bhagwandin. He has been instrumental in putting together data going back to 1985. The dataset shows that each year from 1985 to 2016, the CF had a negative balance or an overdraft. This data will be made public soon in our forthcoming paper on the “Monetary aspects of the persistent overdrafts.” Some readers might recall that the Minister of Finance announced over a year ago that the Budget Speech will no longer carry the summary page of the CF. It is for this reason our dataset stops at 2016.

Nevertheless, as I learned from O’Level and LCC (London Chambers of Commerce) economics, the central bank is the government’s bank. The net of all central government’s expenditures and revenues must be reflected as a liability of the BoG. We reconstructed some data using Annual Reports of the BoG that indicate a major turning point in the stock of government deposits in 2015. The stock of government deposits moved from a positive to a negative balance in the fourth quarter of 2015 (November to be exact). Therefore, it is not only the CF which is likely to be in continued overdraft, but also total government deposits at the central bank.

I mentioned LCC and O’Level exams to emphasise that the idea the central bank is the government’s bank has been removed in the modern textbooks of monetary economics. If one does post-graduate studies in economics and uses the standard monetary economics textbooks of the mainstream – for example, Carl Walsh’s ‘Monetary Theory and Policy’ or Michael Woodford’s ‘Interest and Prices’ – there is no mention of this idea. The same can be said for Mishkin’s famous undergraduate textbook, ‘Money, Banking and Financial Markets,’ which I assign when I teach a course with the same name. Fortunately, scholars in the post-Keynesian tradition still underscore this important point.

As a matter of fact, there has been a lot of debate recently about a central bank’s ability to finance social objectives in addition to one of its traditional roles of buying and selling securities in the secondary markets. This debate relates to a set of ideas – known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – which were proposed by a group of progressive economists in the United States. Many mainstream economists find the ideas of MMT dangerous and some have more nuanced disagreements. My interest in the debate lies in the tendency towards an MMT-like operation in Guyana and many other developing economies. I use the term MMT-like because the spending or overdraft on government deposits creates excess liquidity in the banking system. These excess liquid assets, I have noted in previous research, represent an attempt to lean against the international headwinds while trying to meet domestic social objectives. In other words, the excess liquidity provides a short- to medium-run policy wiggle room. Unfortunately, this point is often lost in the persistent monetarist worldview of economists at the multilateral agencies. The question is seldom asked about how to enhance and optimise the policy wiggle room in countries without a global reserve, vehicle or invoice currency.

One of the reasons Guyana gained political independence is to have one’s own central bank and national currency. Having a central bank is both a privilege and a potential curse, depending on how the persistent overdrafts are managed. The adverse consequences also largely relate to whether the country is cohesive or vulnerable to ethnic, religious or class conflicts – and not so much whether the central bank is independent or not. The central bank independence literature completely misses the point of social cohesion and the ability to target inflation.

Furthermore, our type of economies do not possess a global currency which is traded in the main financial centres, such as New York, Chicago, London, Tokyo or Singapore. This means the demand for the Guyana dollar is restricted to nationals and foreigners inside Guyana. Zero international demand for the G$ implies that Guyana comes up against the wall of troubles much sooner, particularly if the overdrafts are used to finance public sector wages and fund activities of a political base – hence the reference above to political conflicts. As the MMTers argue, this limit does not exist when the country has the reserve currency and a flexible exchange rate – as does the non-cohesive United States or cohesive Japan. If the limit exists for the USA, then it is a far way into the future, unless the present American President continues to make the choice to unravel that country’s immense global financial privileges.

The Guyanese monetary authority also chooses to manage the exchange rate instead of allowing it to be completely determined by market forces. There are advantages associated with managing the exchange rate. However, the management becomes more complicated when the overdrafts become excessive. In recent memory, there were lively discussions surrounding the pressure in the foreign exchange market and the reasons for the depreciation from around G$206 to about G$217 these days. It was noted from some quarters that the Cubans and Caribbean nationals are taking out the US$ notes, as well as the dismantling of the fabled narco-economy.

However, the turnaround from a positive balance to a negative one (overdraft) in 2015 gives a more logical explanation for the depreciations. Why? Because the overdrafts reduced the amount of foreign exchange available in the local system as people demand more foreign goods and services, as well as hoard more foreign currencies. There is some evidence supporting my point. The total US$ purchased by the bank and non-bank cambios amounted to US$1.424 billion in 2014. This number dropped precipitously by US$143.8 million to US$1.280 billion in 2015, thereby indicating the official trading system lost foreign currency. For the same two years, 2014

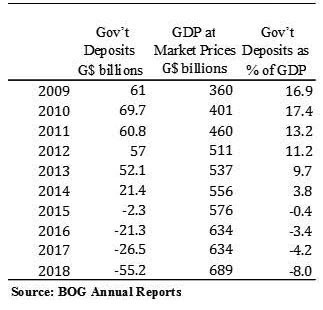

The Table reports for the period 2009 to 2018 the annual stock of deposits at the BoG. As is obvious, the government cranked up its overdraft spending from 2015, when the numbers turned negative. I also report the nominal GDP so as to express the deposits as a percent of GDP. In 2009, these deposits were 16.9% of GDP and by 2018 they turn to negative 8.0%. Observe also that the nominal GDP did not change from 2016 to 2017. However, the exchange rate adjusted with a depreciation as output stagnated.

I made it sound like there are always dangers associated with this policy of overdrafts. In the next column, I will explain how this approach provides a wiggle room for governments to achieve social objectives even when they do not possess a globally traded currency. We will also answer the question whether the government has to repay the overdraft and whether it should be added to the stock of national debt.

Comments can be sent to tkhemraj@ncf.edu