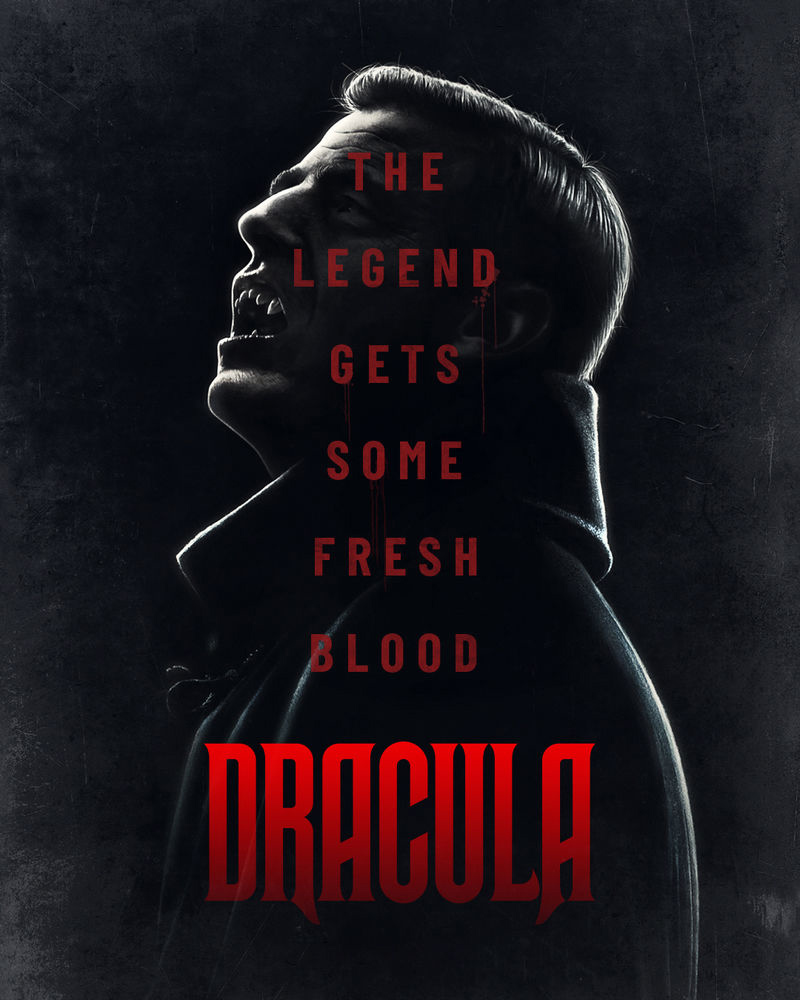

As the movie industry slows to a halt, now is as good a time as any to turn to the digitised media that’s available. A number of films have accelerated digital release over the past week in response to the coronavirus pandemic, but this week I turned to television – and Netflix’s ever-expanding collection of TV series. The streaming giant started off the year ominously, with the BBC One co-production of a new adaptation of “Dracula” that seemed to fall under the radar, despite the talent involved. Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, whose reinventive riff on Sherlock Holmes (another Victorian era character) made them staples in the industry this last decade, and their recreation of “Dracula” follows in similar footsteps – at once extremely faithful to the source material and at other times, virulently its own thing. “Dracula” is, perhaps, even more of a cultural inevitability than Holmes, a Victorian era figure that has defined representations of vampiric lore over the past century. And this new adaptation is immediately aware of that.

There’s something to be said about the way that 19th century literature has endured as the bellwether of so many literary adaptations for the past three decades – from Dickens to Jane Austen, from Mary Shelley to the Brontës, these characters seem suffused in our contemporary world. Dracula, as a character and a symbol, is immediately tied to the paradoxical nature of Victorian mores he emerges from and also immediately liberated from them because of our own ever-present fascination with the occult and vampires in general. There’s nothing quite like this new Dracula on television, and that is less to do with the way Dracula is than with the way television has been deployed in the last few years. This is not Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” or Francis Ford Coppola’s “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” but it inevitability follows the lineage of all that come before it.

We begin familiarly enough, but with a twist. Jonathan Harker, an English lawyer, travels to Transylvania to assist Count Dracula with a property purchase in England, and soon enough we realise that Harker’s property purchase is a mere guise to provide Dracula with a steady meal to regain his youthful appearance. The set-up is similar to previous versions, but this first episode – nodding to the epistolary fashion of the novel – is set up as a memory as the ill Harker, recently escaped from Dracula, tells his story. Gattiss and Moffat structure the story over three ninety-minute episodes, each with a different focus covering the tale of Dracula’s perversions over the course of the miniseries’ running time.

It makes for much curiosity. Instead of a tale about a group figuring out Dracula’s motivations and foiling them, this version centres the Prince of Darkness. In privileging Dracula as his own hero rather than a foil for a band of do-gooders, Gatiss and Moffatt open up the story to thrilling possibilities of dramaturgy but it’s a situation with split differences. Claes Bang, for example, is doing all he can and should do as Dracula. In an intriguing turn, the show draws well from having him play Dracula as neither a menacing interloper or a particularly charming rake – he is neither hypersexualised or especially scary, but instead consistently regular. It makes for an interesting schism between appearance and intentions but it also creates a strange airlessness to his performance as it goes. It makes for an interesting dynamic, but with the majority of the supporting players so thinly drawn by halfway through the second episode I found myself wondering who to be invested in. And we do have a linchpin focal point there, albeit in unusual ways.

In the series’ central deviation from its source, the only real foil for Dracula is Agatha Van Helsing, a nun who replaces the original novel’s Abraham Van Helsing. Like her literary predecessor, though, she too is equipped with knowledge of vampiric lore and ready to challenge Dracula to his death. As played by Dolly Wells, she is pragmatic to a fault, intrigued and contemptuous of Dracula. Wells is the show’s best asset in a performance that’s always complex and complicated. Nothing in the miniseries is faultless, but Wells’ complicated performance is exactly the fulcrum it needs, moving from tetchily annoying to dependable to revelatory as the show goes on – she’s especially excellent in the show’s second episode, which employs a much riskier epistolary style than the firstand which doesn’t always work. It’s shrewd and compelling work and it’s evidence of the series’ best impulses – whether or not this is apt to be anyone’s favourite version of Dracula there’s a level of care put into this that feels bound to enrichen on re-watch.

Nothing in the later two episodes approaches the gothic splendour of the first house – the first episode treats us to not one but two houses of entrapment and the moving between two timelines, for of course we begin in media res, which is incredibly effective there. It’s not the actors around them are doing poor work but there’s not a great much for them to do – Gatiss and Moffat are a slave to the environment and mood, and that seems apt for an adaptation of “Dracula”. John Heffernan plays a delightful patsy in the first episode as Harker, Matthew Beard is a diffident Jack Seward and Morfydd Clark plays the innocence of Mina Murray in surprisingly tender ways. But, it’s mood more than characterisation that defines this and by the third episode (predicated on a twist that’s exemplary, even if it doesn’t quite sustain itself) the atmosphere dwindles for reasons both obvious and less so than threaten the tone of the entire thing. The resolution of the tale lacks the panache and visceral drive of its predecessors, in a way that feels too pat for a story that’s been so intent on prickliness. But, it’s as good a reminder that a series is not as good (or bad) as its end.

As far as creative ambitious and thoughtfulness go, “Dracula” is a compelling literary adaptation that joins the similarly inventive (if superior) adaptations of “David Copperfield” and “Emma”. It’s likely that this new decade will find us digging even further into the wells of other 19th century tales so perhaps we can look forward to Gatiss and Moffat adapting some Thomas Hardy in the near future.

“Dracula” is available for streaming on Netflix.