The Caribbean Press was one of the institutions created out of a rare productive confluence of minds between artists and politicians during Carifesta X, 2008, in Georgetown. The Grand Opening Symposium at that festival ended up with the common debate over where a government ought to place its priority – should it build a theatre or use the funds to build a road. The main protagonists were Sir Derek Walcott on one side and then president Bharrat Jagdeo on the other. But the supporting cast included writers David Dabydeen, and Earl Lovelace, as well as Dr Frank Anthony, who was minister of culture at that time.

It was a festival affluent in literary talent and scholarship, whose principal actors also included Barbadian-Canadian novelist Austin Clarke, Surinamese novelist Cynthia McLeod, Caribbean poet and critic Edward Baugh and legendary choreographer and pioneer in Cultural Studies Rex Nettleford. In the presence of that distinguished gathering, this common debate on national priorities culminated in the uncommon outcome of funds being provided for the establishment of the Caribbean Press.

It was indeed a rare and momentous development, giving rise to a publishing house entirely devoted to the arts, history, scholarship, and an outlet for new and developing writers. The press set itself goals. In a very instructive summary of the history of colonial literature in British Guiana, it made the remarkable observation that in the 18th Century “there was no contradiction between the manufacture of odes and that of sugar” in a materialistic society of slave owners for whom “the refinement of art and that of sugar were one and the same process”. By the time of independence (1966), Guyanese writers “attempted to purify literature of its commercial taint”.

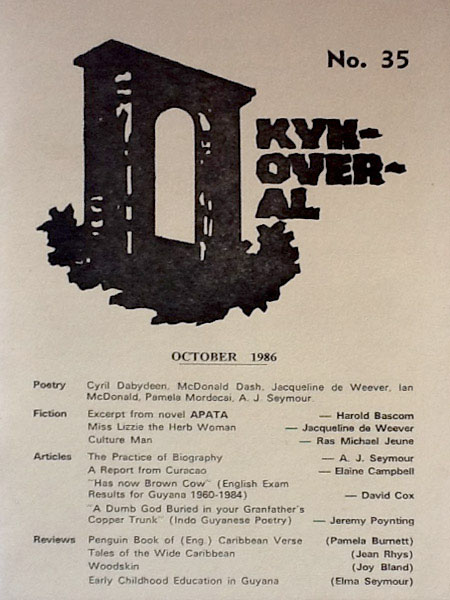

As its first goal, the Caribbean Press started up the Guyana Classics Library, with an aim to “republish out of print novels, poetry and travelogues so as to remind us of our literary heritage” and “of our reputation for scholarship in the fields of history, anthropology, sociology and politics through the reprinting of seminal works in these subjects”. The General Editors were Dabydeen and Lynne Macedo, with Ian McDonald as Consulting Editor. Their first focus was making available selections from the most important Guyanese literary or historical texts, restoring them to life. Among these seminal works was Kyk-Over-Al, founded by the B G Union of Cultural Clubs in December 1945 and edited by A J Seymour, foremost poet, and critic of that time.

Kyk-Over-Al, which Seymour often referred to as a “little magazine,” was a literary journal with a hallowed place in the history of West Indian literature. While its making included much that went before in colonial history, modern West Indian literature was truly shaping itself early in the 20th Century through different initiatives. These included the founding of social realism in fiction through the popular novels of H G De Lisser, first published (serialised) in the pages of the newspaper he edited in Jamaica, and the continuation of kindred literary movements with the deliberate promotion of social realism in Trinidad between 1929 and 1939. In British Guiana, similar developments may be attributed to Edgar Mittelholzer in 1941 with the publication of Corentyne Thunder. The major push took place after the Windrush from a London base in the 1950s.

But invaluable contributions were made by the literary journals in whose pages developing writers found outlets which supported their growth and confidence as writers and helped to shape and define the literature. Trinidad (1929 – 1930) and The Beacon (1931 – 1939), two journals edited by C L R James and Alfred Mendez, aggressively drove a progressive local literary consciousness. Bim was founded in Barbados in 1942 and edited by Frank Collymore, and for a long time after nurtured the poetry and short stories of many who were to progress as West Indian writers. Focus was another, founded in Jamaica in 1943 and edited by sculptress and intellectual Edna Manley. It saw the rise of the likes of Roger Mais and M G Smith. Kyk-Over-Al played a similar role from its first volume in 1945 up to 1961. These were to be joined by Caribbean Quarterly in 1949, a publication of the UCWI Extra Mural Department, first edited by Philip Sherlock.

The early issues of Kyk-Over-Al were extremely instructive in what they revealed of the Guyanese literature of that time. It strove to sustain and define West Indian poetry, in particular. There were occasional poems from Collymore in Barbados, as well as from Sherlock and others from Jamaica. The reprints benefited from a scholarly critical introduction by Michael Niblett, which placed the journal in context, fitting it into the historical background and the growth of Guyanese literature up to the present time. Kyk outlived all the other journals of the 1940s, going out of existence in 1961, but resuming in the 1980s to become the longest running journal in the region, outlasted only by Caribbean Quarterly, which suffered fits and starts but is very strong today.

Niblett observed the way Kyk helped “to develop a more fine-grained understanding of the evolution of Guyanese literature”. He wrote, “This is especially so since in addition to fostering new literary talents, Kyk-Over-Al sought to preserve and bring to attention the work of earlier Guianese writers, thereby not only ‘moulding a Guyanese consciousness’, but also ‘recording its tradition’, as Seymour put it”.

Occasionally, Seymour included a poem from Egbert Martin (Leo), from the late 19th Century, and from Walter MacArthur Lawrence (1896 – 1942). Leo deserves credit as the founder of modern Guyanese literature with his deeply identifiable poetry and short stories in the 1880s. Surely, a sample of Lawrence was demonstrative of how the poetry was developing at that time. Seymour reprinted excerpts from his “Ode to Kaieteur”. Lawrence’s poetry reflected an earlier period in the poetry of British Guiana when poets were still imitating English Romantic and Victorian verse. Although he was truly a Victorian, Leo had risen above that and began to make the verse Guyanese. Lawrence lived through the period of imitation but had enough talent and thought to navigate a path from it into something identifiably Guianese.

Characteristic among the imitative verse was landscape poetry, with poems about the natural environment. English settings were copied, including the temperate climate. Some examples of this type have been preserved in a collection edited by C E J Ramcharitar Lalla, but another development could be discerned among the same group of poets. That was the development of a sense and feeling of nationalism. There was a long period in the colony, starting with Joseph Ruhomon, of the growth of Indian consciousness. Several cultural clubs developed which sustained this over many years. Parallel to that was similar growth in African consciousness, directly promoted by Norman E Cameron, but also buttressed by the Garveyite movement.

As he elevated the imitative into something a bit more Guianese, Lawrence used the landscape to promote national natural beauty and a sense of patriotism. Thus, developed his poems like, “O Beautiful Guyana” and “Ode to Kaieteur”.

By the time Kyk-Over-Al had circulated its first 13 issues, local poetry was solidifying into a gradually growing nationalistic verse. It was outstripping imitation and finding a local identity. An examination of the selections in these volumes demonstrates this very well. Strong local poets were emerging, finding their own voices, and keeping above the common practice. These include, in fact, were led by, Wilson Harris, Mittelholzer, Seymour and Helen Taitt.

This period of Guyanese literature has been made much more accessible by the republishing of this magazine. It is an immeasurable service to Guyanese and Caribbean literature.