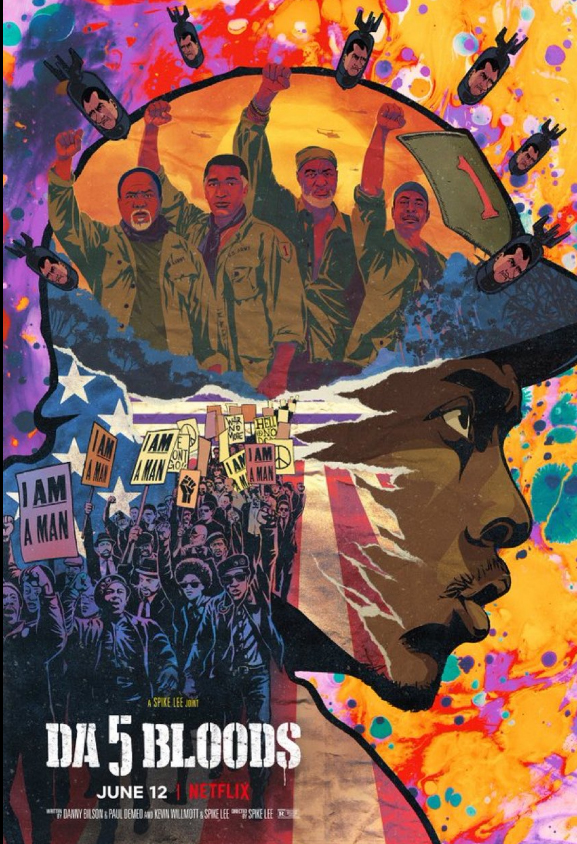

Every interaction of our lives is affected by the weight and history of things that came before – our politics, our forefathers, exigencies of power, the meeting points of class, race and gender. Context affects everything. Even when, or especially when, it is left unexamined. This knowledge is an essential part of the new Spike Lee joint, “Da 5 Bloods,” which premiered this month on Netflix. The new film comes to us soaked in dread, anger and righteous indignation, juggling multiple themes, forms, and motifs to tell a story that feels messy and trenchant in its multitudes. It is a story of war that never ends, so much so that the film seems to be at war with itself.

The first words of the film are an instructive critique of what’s to come. “My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother or some darker people or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what?” This excerpt, from Muhammad Ali’s 1978 invective against the Vietnam War, opens the film, which spends the first three minutes on historical footage. We see Malcolm X speaking in 1962. Images of Harlem in 1970. Angela Davis speaking truth to power in 1969. And images and video of atrocities in Vietnam. It’s a montage of historical renderings that’s interrupted when we meet the four central players – four black Vietnam veterans reunited in present-day Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam.

At first, the story is straightforward and almost at odds with that cold open. The four veterans are on a recovery mission back to Vietnam, ostensibly for the remains of a fellow soldier who died during the war. But the recovery is not just for the remains of a lost brother, but a planned retrieval of minted gold bars (an incisive nod to gold paid to indigenous Vietnamese who joined the Americans in their monstrous war). And, so the film develops as a straightforward mission with some occasional digressions at first. Each man is carrying his own scars, particularly the mercurial Delroy Lindo as Paul – a jaded veteran, suffering PTSD and whose malaise is manifested in his Trumpian “Make America Great Again” hat, his hallucinations and his short temper. But nothing is ever one thing. And even this adventure-gone-awry story is dealing with more than just high-octane thrills.

Early in the film, the four Bloods head to a bar in Vietnam, and in glorious unsubtlety the camera cuts to a DJ flanked by a poster for Francis Ford Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now”. It’s very much like the notably fearless Lee to invoke American cinema’s most memorable treatise on the Vietnam War so early in his film. But the invocation plays as both a teasing nod and a necessary contrast to where “Da 5 Bloods” will go. This is not “Apocalypse Now.” This is not “The Deer Hunter”. This is not “Platoon”. “Da 5 Bloods” only encounters the warzone of Vietnam in brief flashbacks and instead it is focused on the way the remains of a war endure. And, importantly, it centres the black experience in American war history, emphasising the cognitive dissonance of being black and American.

In this way, “Da 5 Bloods” becomes a restless meshing of a very straightforward adventure story, with vignettes of a forgotten war and an underbelly of visceral race critique. These things don’t often go together, and Lee is stressing that dynamic here as “Da 5 Bloods” stresses the seams of unions that don’t quite make sense. The resulting chaos occasionally borders on incoherence, except it feels limiting to indict “Da 5 Bloods” for the ways that its multiple selves seems to be at war with each other. Spike Lee is many things, but careless is not one of them.

“Da 5 Bloods” is a deliberation on messiness and uses its chaos as a deliberate cudgel. It’s moralistic, it’s argumentative, it’s overwrought with symbolism and because of that is lacerating, overwhelming and emphatic even when – and especially when – it is frustrating. The film’s visuals reflect this as cinematographer Newton Thomas Sigel makes use of four different aspect-ratios throughout, moving between different visual cues to punctuate the fractured lives of these characters. The first flashback to Vietnam at war is punctuated by an evening tableau outside a bar cutting, jarringly, to a widescreen image of a sun. As a helicopter flies towards us, the 2.39:1 aspect ratio slowly pushes into a 1.33:1. It is a stunning visual moment and also a cue for the way that the film presents the lives of these men as continuously shifting.

Lee is telegraphing his tropes and conventions to us, so that – I suspect – the film’s bloody climax, its resolution and the final embrace at the end are all things we anticipate happening. But it is all deliberate. The dread that the film amps up is not from the unexpected, but from our certainty that chaos is imminent and our captive waiting for it. It’s a metaphor, like so much of Lee’s filmmaking often is, for the world we live in – the world that came before and the distressing ways that two divergent worlds retain problematic structures of race and inequality. The film’s violence and bloodiness come in various ways. The flashbacks are expected. But mid-film, we encounter additional means of carnage when the remaining mines in the Vietnam jungle come into play.

The men’s trek to the jungle is deliberately evocative of the journey into darkness in “Apocalypse Now”, and Lee gives each remaining Blood (played excellently by Delroy Lindo as Paul, Clarke Peters as Otis, Norm Lewis as Eddie and Isiah Whitlock Jr as Melvin) much scope for emotive turns as they wrestle with themselves and each other. When Paul’s son, David (Jonathan Majors who gets better as the film goes on) appears, the situation becomes more complicated than we anticipate, centring on the personal demons of Paul and allowing Lindo to manifest a character that seems part King Lear and part Lieutenant Kurtz and all bombastic glory. Paul’s arc is the film’s most ambitious, saddling Lindo with soliloquies played to the audience that threaten to teeter off-course. But the ambition pays off. It gives Lindo a chance for expert work, distilling the pain and regrets of a man teetering on the brink of his mind.

Late in the film, a trio of French mine detonators show up. The three are the most prominent white characters, and seem to be excavating their own colonial sins – literally, they are mine detonators. It’s such an overly symbolic touch and evidence of the work that Lee is doing here as every crevice of the film teems with deliberation. “Da 5 Bloods” is less thoughtful on gender than it can be, but then the film’s evisceration of masculinity (albeit, less virulent than its critique on class and race) is potent enough to explain that hesitance. Nothing here is accidental, even in the film’s messiness. No plot-point disappears. Instead, the film reflects and reflexes on itself so that when it ends, what surprises is the sadness and tragedy. “Da 5 Bloods” is angry and indignant. But it is also hopeful and thoughtful. It lingers on in the mind.