Introduction

Today’s column continues my exploration of Guyana’s world class offshore petroleum discoveries located mainly in the Stabroek Block, and under operational control of ExxonMobil and its partners. Two other joint venture groups (JVs) have been acknowledged as being on the cusp of production, but their reported discoveries give cause for considerable uncertainty on this score.

Way back in 2016, when Exxon and its partners’ reported discoveries were less than one billion barrels of oil equivalent (BoE), I was predicting Guyana’s discoveries would eventually reach 13-15 billion BoE. That prediction is not based on “guesswork”, “gut feelings”, or indeed “intuition”. It depends on two lines of reasoning, flowing from my research into Guyana’s petroleum in 2015. The first of these was presented in last week’s column—that is the “Atlantic mirror image” geological principle. The second reasoning is derived from two United States Geological Service (USGS) Fact Sheets, released in 2000 and 2012.

USGS Assessment

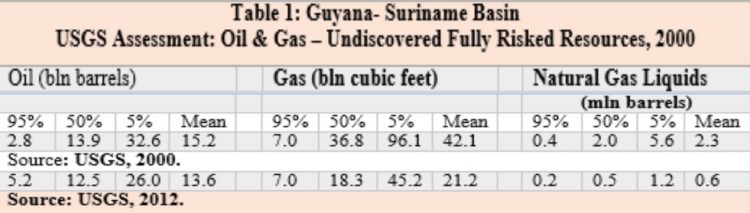

These Fact Sheets summarize data from two USGS’ World Energy Assessments of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources for the Region: Central and South America as well as the Caribbean (2000 and 2012). As previously indicated, the information provided there is “fully risked”, and the estimates are provided at levels of 95, 50, and 5 percent probability. The mean probability is also reported (where fractiles are additive, assuming perfect positive correlation). Further, the estimates provided for natural gas include natural gas liquids separately.

“Undiscovered” gas resources, as provided, are the sum of non-associated and associated gas. Both Survey results are summarized in Table 1.

For the 2000 assessment, estimates range from 2.8 billion barrels of oil (95 per cent likelihood) to 32.6 billion barrels (5 per cent likelihood). The 50 per cent likelihood is 13.9 billion barrels of oil equivalent and the mean is 15.2 billion BoE. For the 2012 assessment, estimates range from 5.2 billion barrels at 95 per cent and 26.0 billion barrels at 5 per cent. The 50 per cent likelihood is 12.5 billion barrels and the mean is 13.6 billion barrels. Discoveries thus far by ExxonMobil and partners reveal amounts considerably larger (8+ billion BoE) than the 95 per cent likelihood estimate for both assessments.

Two further observations are warranted at this point. First, these estimates are for a virgin frontier region and therefore remain reliant on detailed petroleum geology assessments to verify. Second, the mean natural gas estimates are for 42.1 and 21.2 billion cubic feet, respectively. And, for natural gas liquids the mean probability is 2.3 and 0.1 million barrels, respectively.

It should be recalled that these survey assessments were conducted as a subset of the USGS’ World Assessments. Further, the natural gas estimates are reported in cubic feet and natural gas liquids in BoE. The standard conversion ratio of natural gas to BoE is 6,000 cubic feet of natural gas is equivalent to one BoE.

Further Justification

At this juncture, I hasten to remind readers that my prediction was first introduced in my Sunday Stabroek News Columns of October 2-9, 2016. Later, I returned to this topic in columns on the Guyana Petroleum Road Map, (February 10 – 17, 2019). Recently, I revisited these issues in my contributions on the Buxton Proposal series of columns.

Of note, this issue has re-surfaced as “news” in local print and social media. It is becoming increasingly evident to analysts and researchers that there is a rapid “advent” of world class petroleum finds in the Guyana-Suriname Basin. Thus in March this year, Exxon’s Chairman and Chief Executive Officer disclosed that despite the severe setbacks the supermajor was facing, (given the state of the world market for crude): “Guyana will be assured of high priority … at least for the next five years” (my emphasis). Based on such commentary the public policy group American Security Project, ASP has predicted that Exxon’s projection of 750,000 barrels of oil per day from Guyana “could be a considerable underestimation” (my emphasis). The ASP posited that, if all goes smoothly in permitting oil production: “output could rise to over one million barrels per day by 2030”.

In a forthcoming Chapter [Guyana and the Advent of World-class Petroleum Finds], I offer the following observation: “ExxonMobil’s public reporting reveals that wells dug to date and recorded as successful [now 16] suggest a success rate [in excess of 80 percent], which is, four times the global average [thus far] of less than 20 percent! Significantly, [the company] reports the breakeven cost for this oil as being less than US$35 per barrel”.

Back in 2016 I had also acknowledged that I was “strongly bullish” in my outlook with regard to Guyana’s petroleum resources potential. I had also acknowledged that, to the contrary, I was “deeply conservative” in regard to my expectations as to the Government Take ratio, which would be attained under the present PSA and any improvement of this ratio as time progresses. The reasoning for the latter is that the prevailing ratio dictates the rapid advances in exploration, discoveries, and, particularly, Guyana’s transition from discovery to production and export of petroleum products. If it is significantly changed, investment flows will also be changed.

Conclusion

Given my bullish outlook on Guyana’s resource potential and production over the coming decades, several strategic issues arise as regards the role Guyana should strive to play in the evolving global oil economy. Two of these warrant early consideration, even though we are at present, decades away from having to confront them. One is Guyana as a “swing producer”; and, the other is Guyana’s attitude to OPEC.

These will be addressed next week before I turn to assess the immediate near-term impacts of the 2020 general crisis.