In “The Personal History of David Copperfield”, Armando Iannucci’s adaptation of Charles Dickens’ bildungsroman paints the varied locales of Victorian-era England with strokes of playful whimsy that bleed into its mood and form. But more than that playfulness, what emerges most significantly in this new “David Copperfield,” where David announces his desire to write (and right) the key moments of his storied life, is its self-reflexive and self-conscious awareness of the ways that writing and creation are acts of reclamation, incision and even desperation.

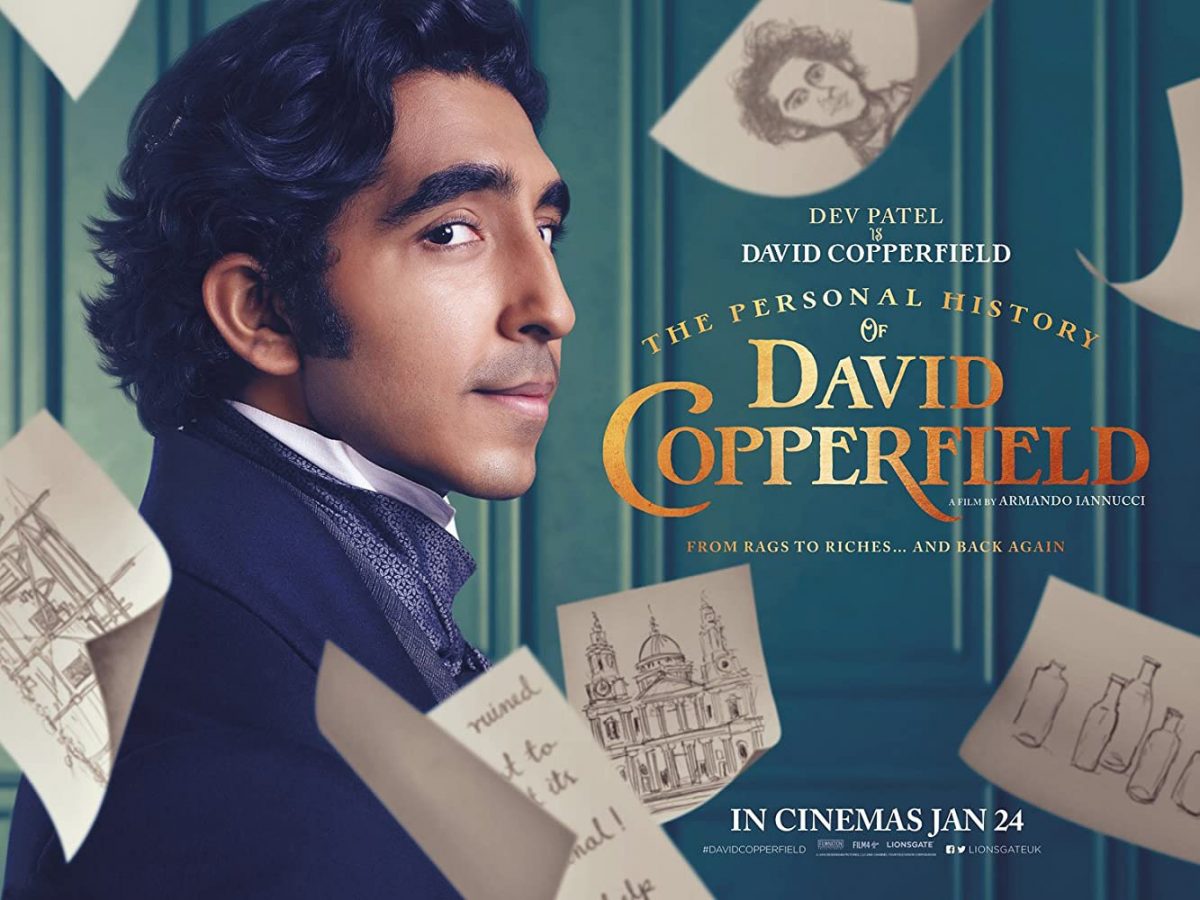

The brief opening scene sets this up. Dev Patel steps on to a lit stage in a packed theatre hall. This is our David Copperfield. He stands before a lectern, looking out at the audience and begins to speak as the entrance-applause subsides. “Whether I turn out to be the hero of my own story, or whether that station will be held by anybody else…these moments must show.” And with that he turns from the audience and steps through the wall of the stage and into the fields of a Victorian countryside, immediately transported through time and space in a moment that feels immediately absurd and thrilling. For David, writing means thrusting himself into the past.

Dickens’ novel, narrated in the first person, is a 600-page account of a fictional character that is structured like an autobiography, with all the digressions and peripheralities that a life lived well would suggest. Iannucci transfers the first-person style narration of Dickens’ original novel by presenting the film as the story that the David from the beginning is recounting to us. Instead of overhead voiceover narration, the linear tale of his life is punctuated and then pierced by occasional fourth-wall breaks as David – and even the other characters – contemplate the illusory nature story that he is creating. The most instructive of these moments happens near the end of the film

In a climactic moment as the film’s central villain is unmasked and vanquished and the major players of David’s life flank the room to observe until the moment of righteous vengeance is pierced by a character (Dora – the object of David’s youthful infatuation) turning, confused, to David to intone: “There’s no reason for me to be here.” It’s a moment of precise intentionality, as Iannucci seems to be reaching back to Dickens’ original novel and mulling on the novel’s own intentional digressions. The question of what fits, and what does not, is an important part of the way David recounts his tale. He calls them “living memory” and it’s clear, from the frenzied way the film deploys them, that his writing is a way of working out the best and worst of himself.

Iannucci, who directs the film and cowrites it with Simon Blackwell, is performing something more intriguing than docile fidelity with this adaptation. The vastness of David’s life and the varied characters in his life story are kept from seeming disjointed by precise focus on ensuring that each episode in David’s life is part of a specific through-line that will lead to some payoff in his maturity. And how lucky for Iannucci that his limber direction is supported by Patel, who (after an opening twenty minutes with Jairaj Varsani as a young David) is the exact embodiment of the hearty and wholesome heroism that Dickens’s protagonist demands.

The film, with some amendments, follows the novel as it takes us from the birth of our young would-be hero to maturity as he learns the ways of being a man. In that moment, when Patel steps through the frame he is taking us back to the Rookery, where he (and us) watch his frail mother give birth to him. (The glorious shot of adult David looking at his infant form is a nice touch. That first scene in the past is a flurry of entrances and exits as the film breathlessly tries to give us all the information needed to set up context. That flurry does not let up for much of the film. And, in many ways, it makes sense that such breathlessness accompanies much of a film that’s adapted from a 600-page novel. The pace of the film is relentless, but also purposeful.

As David moves from an idyllic young life, to a miserable factory-life of drudgery to boarding school, the film retains a gossamer-like metatextual quality as it intimates (often through Patel) that this is as much a life as it is a story being created and then recreated as a life. Even as David encounters hardships, there’s a looseness to the comedic idiosyncrasies that Iannucci ekes out of Patel that keep the film warm even when it is bleak. And so, Iannucci succeeds in turning this into a film about the craft of writing. Shot after shot we watch David writing and recording his life, and in a fantastic bout of comedy we watch Patel imitating the people he encounters. The joy he takes in impishly recollecting oddities of those around him presents a perverse thrill. For David, the gentle mockery of his writing is his coping mechanism.

And, so the film seems to depend on all things being somewhat heightened. This is memory, not real life. These moments, where the narrative reflexes onto itself, drawing attention to its own fabrications are the most thrilling, both for thematic and formal reasons. There are a series of scenes where memories are projected onto surfaces where Zac Nicholson’s cinematography is at its most incisive. And there is also an earlier scene where a giant hand breaking the roof of a house turns into the angry hand of a stepfather destroying a child’s artwork. At times, Iannucci abandons the metatextual references and returns to something a bit more straightforward, but then the film rights itself when it writes its way out of reality into something more ambitiously unreal. The penultimate shot of two Davids in conversation with each other is proof of this.

And what of Iannucci’s decision to cast the film with a composite of races? Patel’s David Copperfield of Indian heritage. His mother is white. Agnes, his would-be paramour, is black. Her father is played by an actor of East Asian descent. It affects very little in the film’s narrative. There are strains of subtext in some scenes. For example, in a critical moment, Patel is flanked by four white bodies as David makes his first decisive strain towards owning his fate. But mostly, the film is deliberately ambivalent about commenting on the racial implications of the casting. Instead, it is better reflected as a chance to give different bodies a chance to enjoy the frivolity of Victorian-era joy. Iannucci understands that the idea of “blind-casting” is best considered as a way to give performers opportunities they might not have had. And Patel is more than up to the task. As good as Jairaj Varsani is as a young David (and he is very, very good), the film is at its best when it allows Patel’s unbridled emotion to push through. It is the best he’s been yet. In that climactic moment when bellows, “My name is David Copperfield!” it feels like a benediction. It feels like the role he was born to play.