By Patrick George

“Shut yuh damn mouth, yuh late!”

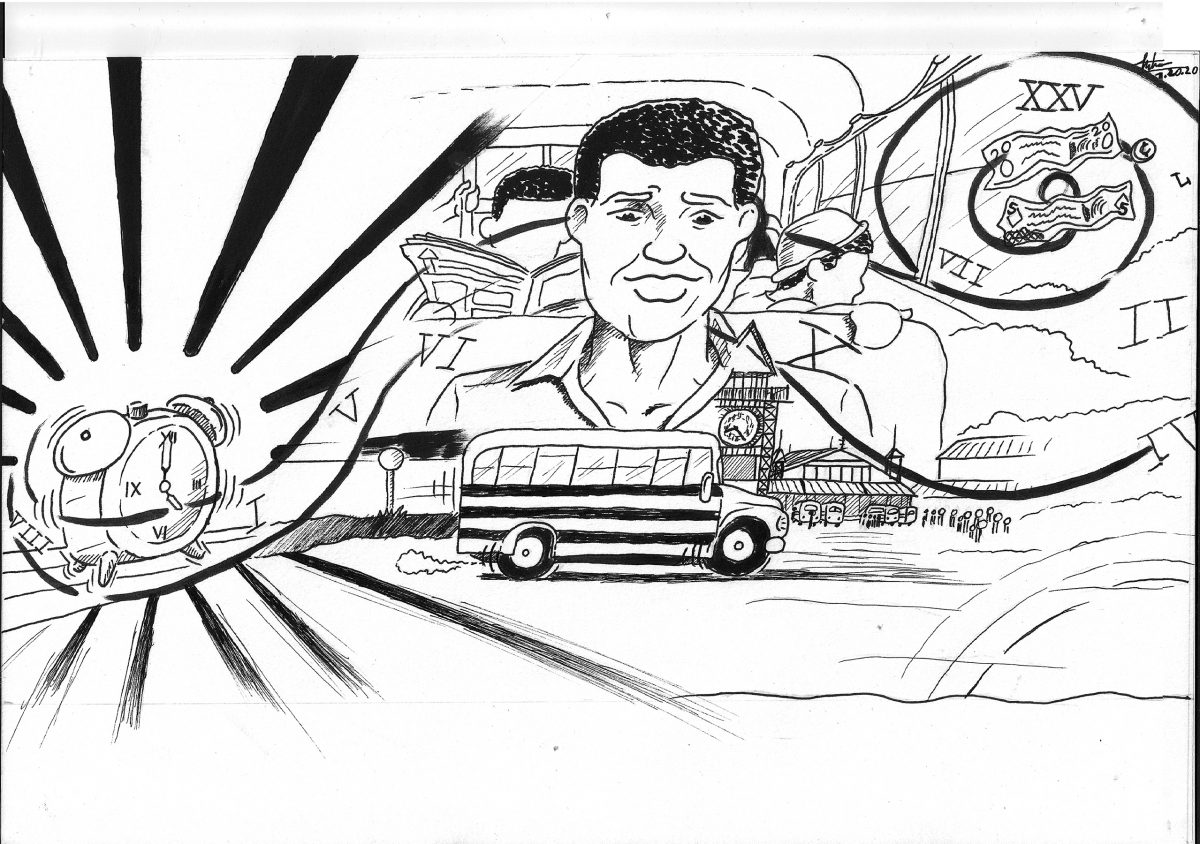

Hot words cutting through the silence of a cool morning, only just rising from slumber to meet the new day. But harsh as they were in composition, there was no defining sting and as a result, they sounded like all bark and no bite. Nothing in the tone of voice suggested that the speaker was as damn vex as he was pretending. If anything, it bore the teasing fondness of one old pal to another, and its virulence was further made a mockery of as the speaker, with a tolerant smile on his mud-coloured face, turned away from the mirror and walked across the room to the night stand beside his bed. Bending over, he pressed the knob on the little blue alarm clock, silencing its impatient and petulant screaming. He rubbed it gently like it were a pet kitten.

He’d won the clock nearly two decades ago, at a bingo he’d been to with his grandmother when he was fifteen, and since then, it had only required two trips to the clock repair man. There was the time after taking a tumble from shelf to floor, resulting in a dent and scratch on its outside, and some shifting of the vital organs inside which required minor surgery, giving it a few days rest from minding human business – and once when a hand, right before Calco eyes – as if planned – froze at nine and time stood still.

“Only kidding, yuh not late old girl, I got up before yuh is all,” Calco said, looking down at the little clock with a doting smile on his face.

Only god coulda come down and convince he that the clock didn’t return a smile. But then again, he didn’t believe in no god, so nobody could tell he that he old clock was incapable of returning smiles – that it was only in he imagination. The same went for de old black an’ white photo of he grandmother stuck to the wall next to the mirror. She always had a Mona Lisa for he whenever he thought or said something smart or funny.

Calco (short for calculations) was just a nickname, one he’d attracted to himself due to his habit of saying ‘according to calculations’ before pronouncing on almost any matter. It started out being his trademark words when eyeing ball positions on a pool table and lining up his cue for the shot – he’d take measurements on the pool table with his cue and then exclaim with confidence that ‘according to calculations’ he was going to drop the ball or balls in this or that hole. But over time it had progressed to him using those words before positing any opinion; he’d shake he big head from side to side and pout out he bottom lip before or immediately after the utterance. And that is how everybody who know he started calling he Calculations or Calco. He was nearly always right with his pool shot calculations but not so with his other calculations and sometimes found himself squirming in hot water.

The little clock had been serving him faithfully for two decades and was one of the items in his one-bedroom apartment that he sometimes spoke to like they were his children. Although he’d gone to bed much earlier than he generally did the night before, he’d only managed about four or five hours of restless sleep – such was his anxiety over the coming day’s planned mission. He finished his dressing in front of the vanity mirror, leaving for last the slipping on of his beige Clarks desert boots, a style of footwear which was, like his clock, a habit acquired in the sixties. Even the arrival of platform ‘kickers’ in the seventies failed to make him completely abandon his belov-ed Clarks. This meant that during that period he owned bell-bottomed trousers of varying length – some to fit his Clarks one-inch sole and some to fit the much higher-heeled platform shoes. After counting out some money and stuffing it into his pocket, he left the house, smiling at the thought that for once he’d eaten breakfast without the annoyance of houseflies swooping down like fighter planes on his food; the little buggers were probably still snoring in their corners.

It was still dark as he strolled along the quiet Campbellville streets, and ten minutes after leaving the house he was standing at the bus shed with two other commuters when the familiar yellow bus, the first for the day, rolled up. A lone, groggy looking passenger got off. Calco lingered behind as the others briskly boarded the bus, and after looking about furtively in the morning dimness ran his hand lovingly along the side of the bus, then shifting his head to the side and leaning in as if inspecting a flaw, ‘accidentally’ brushed his lips against the cold metal. He take he own time climbing into the bus, much to the annoyance of the characteristically fretful driver.

Calco immediately noticed the difference in smell. The later bus that he usually caught never effused such freshness. He thought that this was due to the scarcity of passengers and the early morning breeze sneaking through the open windows, still carrying some dew and leftover night sweetness. At the sound of a cock’s crow he looked out the window into the lightening darkness; in the east there was the beginning of daybreak with sun

peeking out cautiously as if fearful of bumping into lurking rain and causing an uproar. Inside Calco there was the beginning of an uproar – one of sadness and a growing feeling of immense loss.

Mere seconds into the bus’s journey Calco experienced a rush of nostalgia and became almost uncontrollably emotional; a lump formed in his throat and his eyes grew hot and wet. He took a deep breath and then cleared his throat noisily in an effort to stem the tide of emotions weakening him; mind and body. He was glad the bus was almost empty and no one was near enough to see his trembling lips and teared up eyes. The unexpected meltdown was scary. Forcing sound through a choked up windpipe, he began humming a song that he used to sing regularly as a child, a song that would have been popular about the time he first started riding and enjoying the compelling beauty of the city’s yellow buses – ‘hushabye hushabye, oh my darling don’t you cry …’

“According to calculations I was five years old when I fuss climb into one of dese old bus,” he thought, forcing a weak smile onto his sad, dark face.

Calco had decided the night before that he was going to ride the first bus of the day and the last one later in the night. It would be his way of saying goodbye to what he considered old ‘friends’. It was the last day of the buses’ service to the city. They were being taken off the streets by an ailing company, victims of an economic meltdown in the country and the resulting petty thieving that had wriggled its way into the bus office and garage. Bus parts and earnings disappeared in the blink of an eye and had the company wobbling. Calco didn’t care much for the minibuses and mostly ancient hire cars that had already started taking over the transportation business; they were much too reckless and noisy for his liking and also lacked the dependable timing of the bigger, yellow buses. Also, they hadn’t the ‘history’ that he and the yellow buses shared.

The second stop the bus pulled into reminded him of the first day he’d seen his first girlfriend standing in the drizzle – she had shared her umbrella with him – and the first date they’d been on one year later when they were both sixteen. He could clearly picture her in the crisp, neat, Bishops’ High School uniform and the broad straw hat and tie. He remembered how it had taken weeks for him to find the courage to actually speak to her even though she’d been giving him sweet smiles every time they travelled together since the first day.

His hesitation had been due partly to shyness and mostly to the fact that his high school, G.O.C, was not in the same league as hers, the second ranked school in the country, and to boot, she was amazingly pretty, in contrast to his ordinary looks. The only thing he face had going for it was a stolid look of confidence that never budged, regardless of situation, and some of the people he encountered would get blue vex at he just because he poor-ass face always look suh cocksure even when odds were against him. After one year of ‘going steady’, he’d lost his pretty young love to a twenty-five year old, experienced, racing biker with a reputation as a ladies man. The rider, in turn, soon lost her to a ruggedly handsome friend of Calco’s who, through loyalty to their friendship, had been patiently waiting for the chance to make her his. Calco had been deeply amused, for he’d always known of his friend’s crush on the girl, and instead of anger, felt avenged, brushing it off with the consoling thought that at least she was keeping it in de family, so to speak. He now laughed inside at the memory.

Every bus stop along the way held reminders of people, incidents and adventures dating to as far back as his primary school days. Good or bad, each memory brought a smile to his face and a welcomed lightness to his dark, heavy mood; he soon began enjoying the ride punctuated with blasts from the past.

“Life must go on, change is inevitable,” he philosophized under his breath, then added, “but according to calculations dis cyan’t be de end, dey gonna bring back de yellow buses.”

He refused to believe the little voice inside his head telling him it was indeed the end.

A little old guy dressed like a night watchman got onto the bus carrying a tiny radio/cassette recorder that was squeaking out at its maximum output, lovely golden oldies, and the last traces of Calco’s sadness gradually dropped away like waves doing a moonwalk retreat from a sandy beach due to a change in tide.

A nice looking buxom lady followed de old DJ into the bus. Calco looked at she and immediately a popular saying jumped to he mind – thick like butta – and he licked his lips. The lady plumped she thick buttery self, right next to Calco, startling he, not with she closeness, but with the realization that she not only looked like butter but also smelled like it. He glance down at de little brown paper bag she was holding and see de oil stain. According to calculations, she got toast or hot bake in dey, he told himself. The lady noticed his downward glance and mistaking the direction of his gaze, clamped her bared and obviously creamed knees together while side eyeing him with a pretend chide, betrayed by the slight smile on her smooth brown face.

A minute later, miss buttery leaned sideways and whispered to Calco: “Yuh ever notice that every oldies lover does feel that everybody else love that genre, and they does feel dey doing you a big favour by blasting it in yuh ears, given the opportunity?”

Calco was more taken aback by the word ‘genre’ than by the lady’s intrusion. He didn’t expect a big word like genre from miss buttery, and so early in the morning.

“According to calculations, dey right … well, almost,” Calco said.

“Whah you mean, what calculations?”

“Aaahm … just something I read in a magazine. They say that ninety-five percent of people like golden oldies. De five percent who don’t is people who life is and was always miserable, so dey got no nice feelings to look back at and don’t care fuh de music from the past,” Calco lectured.

“So you saying somebody do fancy research and calculations and come up with that… hmmm…interesting…but come to think of it, as you say, dey right…I like oldies,” butter baby said, shaking her head in time with the music.

She continued, “You like oldies too?’

“Yes, bad, bad.”

“And you does read a lot too, eh?” she asked.

“All de time.”

“Me too, I love meh books” she declared, and exited the conversation to begin a soft humming and gentle swaying.

Just before the bus turned into Regent Street, Calco’s dairy seating companion pulled the cord to signal her stop. She turned and extended a soft hand to Calco and squeezed his with a meaningful eagerness as they shook.

“My name is Elaine Bunbury, I work at the Agriculture Ministry…nice to meet you.”

“I am Cal…,” Calco said, barely stopping himself mid-word.

“Cal what? The lady asked.

“Aaah … Henry Weeks,” Calco replied, giving her his full name.

“Cal Henry Weeks…weird name but it sound good tho… yuh could drop in sometimes and we could exchange magazines or novels,” she said, smiling sweetly as the bus slowed to a halt.

“Yuh going to work early,” Calco ventured.

“Some mornings I does go to mass before work… just around de corner.”

Miss buttery got up and daintily stepped toward the turnstile, her lush derriere bouncing seductively under the wine coloured ministry uniform. Calco smiled inside, thinking, ‘Boy, according to calculations, yuh ugly, but yuh damn lucky.’

When the bus finally reached the terminus at the Stabroek Market square the sun was out and life was on the hustle, and Calco had more than an hour before clocking in to work. An idea formed in his head – one that he hadn’t calculated for the night before, when he’d come up with the plan to ride the first and last bus of the day. Without thinking twice about it he jumped onto another bus that was just pulling off, this one going to Kitty, the village adjoining, save for a bisecting abandoned railway track, the one he’d just travelled from. He chuckled like a young boy as he squeezed through the narrow space, barely beating the in-swinging door.

With a satisfied smile on his face he sat down in the seat near the door facing the other passengers. Over the years sitting that way had become a habit to him; he liked looking at the faces of other passengers and trying to guess character, thoughts, problems and kinks by their expressions and body language. It was even more satisfying when the face he was ‘studying’ was that of a pretty female, especially if she looked back at him with interest. He quickly dragged up from his memory-well some of the faces he’d ‘studied’ and in some cases gone on to date.

As the bus reached the Lamaha Street/Vlissengen road junction, his mind flashed back to the first morning on his way to high school when at that very junction, on a plot of peasant farm land across the canal and parallel to the railway line, he saw his first dead body – a man hanging from a rope around his neck, slightly swaying in the wind from a limb on a Jamun tree. He remembered how he’d looked at the lifeless figure without being horrified or in the least disturbed. Over the years, in retrospect, when passing by the spot, he’d often wondered how at the tender age of twelve he’d just accepted it as one of those things and calmly strolled on nonplussed, showing more emotion and concern towards the fishes swimming in the canal and the farmers’ fruits, vegetables and flowers threatened by the prevailing drought season, than to the harsh reality of actual, engineered death.

Across the aisle down to the back of the bus there was a young lady with the looks of a school teacher eying him steadily, but he didn’t try to hold her gaze or return the slight meaningful smile. All he wanted to do was to relax and enjoy the bus ride and passing scenery. But he couldn’t help thinking that according to calculations when it rained it damn well pours – fus was miss buttery and now this nice slim sweetie. When the young woman got up to disembark at the Kitty Market stop, she kept her eyes on him as she made her way along the aisle, and animal instinct, twice evoked for the morning, kicked in, tempting him to get up and follow her out. Instead he looked at his watch and made a mental note of the time.

“There is always tomorrow,” he told himself, but then shockingly realized that there would be no bus for her to be on tomorrow.

He started to get up but the bus had already pulled off, severing him from the promise of romance which had been missing from his life for the last two months, following a bad break-up. For him two months was a drought.

He clocked in for work ten minutes late, and as he went about doing his job, he knew that there was no way he could work all day while his yellow friends were out there breathing their last; he just had to be with them at this critical time. He began plotting his escape by complaining to his work mates and grumpy supervisor of headache and a progressing dizziness.

An hour before the lunch break he went to the washroom where he put water in his hair and as it streaked down his face and neck he bypassed his supervisor and went straight to the manager feigning a sickly face as he whispered a convincing tale of unbearable pain in his stomach.

“According to calculations this should work,” he thought as the manager looked him over, a bit suspiciously – he’d had dealings with Calco before.

It worked though; the manager, albeit with reluctance veiling his eyes and tightening his big lips, sent for the supervisor, and delving into the petty cash canister for some money, got him to call a taxi for Calco, telling them that a receipt from the taxi driver would not be necessary. Both Calco and de supervisor knew that the manager was going to write he own damn fraudulent receipt for more than the amount given to them for taxi fare.

Within five minutes Calco was standing at the Stabroek bus terminus checking out the models of lined up buses, instead of him being at the hospital being checked by a doctor. It was his intention to ride only the older models of buses – those that had been around for a long time – especially the long nosed Leyland that looked a bit like huge yellow dolphins.

For the next four hours Calco rode one old bus after another, going into several city districts, some of them, places that he usually steered clear of because of their squalid conditions and notoriety, but now enjoying their sights, sounds and scents. He took a fifteen minute break to have lunch in a fast food restaurant near the terminus. At three-thirty PM he joined a Campbellville bus and went home. After a snack he set his faithful blue clock to alarm in three hours’ time and jumped into bed to get some sleep before hitting the road once again for the final two hours or so of bus riding.

At ten minutes to eight Calco counted and pocketed his money and walked out into the chilly night air feeling slightly sad, but excited, nevertheless. He joined the eight o’clock bus leaving Campbellville and was pleasantly surprised that there were so many passengers going downtown at that hour. He wondered if other persons were doing the same as he, but then remembered that many people would be heading at this time for the eight thirty cinema shows. As he sat in the bus waiting for it to pull out he had one niggling concern – whether to let his final ride be the last one coming up or the last one going back to the terminus. After some calculating he decided to take the last one going back to the terminus and use a hire car to get back home. By doing this he would be able to take a final look at a large number of the yellow buses parked at the terminus. That would be the best way to bid them all goodbye.

When the bus reached the market square he hopped off buoyantly and immediately started reading the lighted panels on top of the front of the parked vehicles to locate one going to Kitty. There were two, one of the newer models and one of the older ones. He went to the older Leyland bus and found that as usual at this hour, due to the nearby cinemas having just let out patrons from their evening shows, there was a long line waiting to get into the bus. Calco joined the line. But, as almost invariably happens, when there is a long line, as soon as the driver entered the bus, took his seat and began activating the entry door, a few persons from the back abandoned the line and rushed to the door, initiating a mad scramble because nobody wanted to be left out and made to wait another fifteen minutes for the next bus, by which time there might likely be a bigger buildup of commuters. Calco soon found himself in the midst of an each-man-for-himself scramble, about four feet from the bus door. Knowing too well that pickpockets preyed on these conditions, he took his money out of his pocket and held the bills and change for the bus fare tightly in his hand.

Nearly three minutes elapsed and though being so close to the door Calco couldn’t get in. He was pressed against the back of a middle aged woman and on either side of her were two men forcibly pushing against her. Calco thought one or both of them might be ‘bracers’ (perverts who used situations like these to rub up against females). He saw the guy on his right suddenly begin to back out of the crowd and at the same time heard the woman shout, “Thief! Thief!” The other guy also slipped away just as the woman spun around and grabbed Calco’s shirt, still crying out for thief.

A burly man grabbed Calco around the neck in a crunching lock as the woman continued to hold his shirt in a tight grip. Within seconds two uniformed policemen from the nearby outpost, also had their hands on Calco, one gripping the back of his trouser waist and the other, one of his hands. The man released his neck and he gasped for air.

“Officer, this man put he hand in me bag…and look, me money gone,” The woman said, showing the policeman her unzipped shoulder bag.

She added, “I feel he going in me bag an’ I turn round an’ grab he.”

“You went into this lady’s bag?” the policeman asked.

“No sir, there were two guys at the side of her and both of them slip away the same time she grabbed me and started shouting. It must be one of them,” Calco pleaded.

“Officer, he lie! Is he!” the woman cried out, still with a grip on Calco’s shirt.

“Officer is whole day dis man riding bus, I did watching he good good.” A nearby sweets and cigarette vendor shouted.

“Ask Yvonne over dey,” she added, pouting her already, naturally rude-looking mouth in the direction of another vendor a few feet away.

“Is true officer, we thought he was a bracer because he ain got de cut of a pickpocket,” ‘Yvonne over dey’ said, looking Calco up and down, followed by a loud outburst, “Officer look he got de money in he hand, doan let he drop it.”

“Ah tell yuh, I know was he,” the victim cried out and she released Calco’s shirt and gave him a stinging slap across he sweating face and then tried to grab de money from he hand.

The policeman, holding Calco’s wrist, took the bills and change out of his trembling hand.

“Sir that is my money. I took it out my pocket because I know what goes on at this bus rink”, Calco pleaded, his stomach churning and heart pumping.

“He lie!” a number of persons shouted. “Lock he backside up!”

“Y’all come with us to the outpost,” the policeman said to Calco and the victim, whose face was aglow with pleasure from her suddenly gifted fifteen minutes of fame.

“And don’t even think ’bout running,” said the officer gripping Calco’s pants.

He let go of de pants waist, gave Calco a heavy thump in he back and then placed his hand on the service revolver at his side, hoping that Calco would do just what he was warned against – run.

“Watch me stand fuh meh Yvonne,” the first vendor said, and took off behind Calco, the victim, policemen, and about a dozen other curious followers.

The outpost was about one hundred feet from the bus terminus. When the small boisterous group entered, a fat corporal reading a book looked over his thick lensed glasses and scowled.

“What the hell is this? … Y’all don’t give man a minute rest.”

“Corporal this big lady is claiming that this man picked this money out she bag. He is claiming that it was two other young men who pick she, and that this is he own money he was holding in his hand because of pickpockets.”

“What you have to say for yourself young man?” the corporal asked.

“Corporal, this lady hold on to the wrong person.”

“You ain no wrong person, you thief me money,” the woman cried out.

“’Corporal I could prove this is my money, just ask the lady how much she had in her bag. I know how much I have,” Calco said.

“Madam, how much money you had in your bag?” the corporal asked.

“Me ain know fuh sure, bout eight or nine dollars,” the victim said.

“And how much money you had sir?”

“Twenty-five dollars and fifty cents, corporal, and one of the five dollar bills got some phagwah red dye on it,” Calco blurted out after doing rapid calculations of fares spent deducted from the original sum he’d left home with.

“Constable, count that money and check for the dye,” the corporal ordered.

The constable counted the money and said, “Twenty-five dollars and fifty cents and red dye on one five dollar bill.”

‘Officer, must be me money mix up with other people money that he pick,” the woman cried out anxiously, looking a truly sad and defeated victim, with no chance of reclaiming her missing money.

“Lady you asking me to believe that this man in a crowd picking people pocket and he got time to count the money and also see a red mark in the dark, sorry I ain buying that …we can’t charge this man. Constable give the man his money and let him go”

“But if he aint a thief what he doing riding bus whole day, me an meh pardner Yvonne been watching he since midday…if he is not a thief he is a bracer,” the vendor cried out.

The corporal looked sharply at Calco with renewed interest, “You been riding the bus all day?”

“Yes sir, but I can explain.”

“I listening…bracing is more serious than picking pockets yuh know,” the Corporal said, smiling.

Calco’s heart lurched and he felt sweat from his armpits running copiously down his sides, but he managed to gather his nerves and explained everything to the corporal and constables who looked at him in awe.

Somebody in the small crowd said, “Bro, you is a strange cookie.”

Calco laughed, it wasn’t the first time he’d been called a strange cookie and probably wouldn’t be the last, taking into consideration the way he usually crumbled.

“But is a nice idea,” a woman exclaimed.

“A damn nice idea, why I didn’t think ’bout that…I got time to ride a few buses tho, thank yuh bro,” another man said.

The Corporal, looking disappointed that the ‘bracing’ theory had been shattered, told Calco he was free to leave. Calco breathed a sigh of relief and quickly walked out followed by a cheering mob. He thanked his lucky stars for being able to think quickly and make an accurate calculation. He nimbly hopped into the Campbellville bus that was presently being boarded. When the bus reached the end of its journey Calco alighted and went straight to a beer garden further down the street where he sat at the entrance drinking beers while keeping a loving eye on the road, on the lookout for every big yellow engine that rolled by, thinking that according to calculations it was alright to take a little break. He let a couple of the yellow ladies go by without him.

When the last yellow bus pulled off Calco was on it, laid back deep into the familiar, comforting seat that knew his history. He was smiling to himself, in contrast to the sadness bloating his heart and the tracks of tears running down his face.