Introduction

Today’s column starts the wrap-up of my on-going evaluation of several remaining concerns still of great importance to Guyana’s emergent oil and gas sector, in the closing days of the “2020 general crisis,” as I have earlier defined this phenomenon. To recap, those concerns centre on: 1) the volume of the country’s hydrocarbon reserves potential; 2) its potential commercial competitiveness; 3) the expected cost-price relation for crude oil produced; and, 4) the estimated share of Government Take from the sector.

While several gaps remain to be filled in this evaluation, I am only able in today’s column to treat with two of these; namely, 1) the movement from petroleum resource discovery to full ramp-up of production; and, 2) a brief report on the recent announcement by one of the industry’s leading energy intelligence consulting firms, Wood Mackenzie, of its updated estimate of Guyana Government Take ratio.

Delays

As far back as 2016, I had referenced in this Sunday series a 2014 survey of 3,498 commodity discoveries worldwide, covering a period of more than six decades, 1950-2013. That survey had identified how many of those commodity discoveries were converted to production and how long after the discovery this occurred. I am aware that, this survey still remains the premier dataset on this topic.

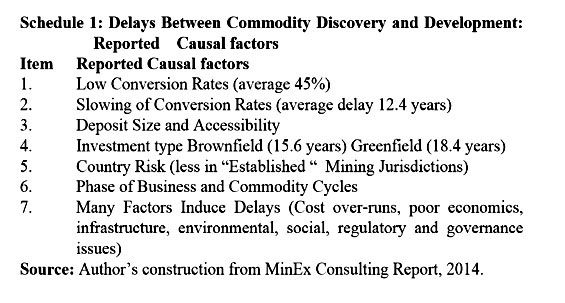

Seven key findings were highlighted in that survey. These are: first, a low conversion rate from commodity discovery to production (45%); second, the average delay between discovery and development has been 12.4 years and lengthening. Indeed, the reported delays have ranged from 10.0 to 18.6 years. Third, the size of a discovery and its accessibility have had a direct bearing on the outcome. Fourth, it matters greatly, whether the discovery is greenfield or brownfield. Fifth, country risk is a most important determinant of outcomes because best-practice mining jurisdictions have performed better than low risk ones. Sixth, the phase of the commodity cycle in which the discovery is made also affects outcomes. And, finally, a variety of other factors have been identified and weighted for their contributions to the observed delays, including: cost over-runs, poor economics, infrastructure, regulatory/ governance.

For the convenience of readers this information is summarized in Schedule 1.

Stranded Assets

At the forefront of today’s global discussion of the hydrocarbons sector is the notion of “stranded assets”. These refer to a company’s balance sheet that rapidly diminishes in value as a result of forced assets write-offs. In other words, assets that have become obsolete (non-performing) well ahead of their useful life, and therefore should be recorded on the balance sheet as a loss of profit. In the case of oil, this portends a serious risk facing the commercial production of fossil fuels in today’s global environment.

Reflecting this concern, the Carbon Tracker Initiative (CTI) has claimed that, in order to prevent global warming, the following is essential: 1) a halt to rising levels of holdings of global coal, gas and oil reserves; 2) a slowing of their projected rates of utilization; and 3) the promotion of sustainable development based on a low carbon agenda. If otherwise prevails, then about two-thirds of carbon reserves are in effect “unburnable” over the long term. That is, around 38% of known oil and gas reserves could be imperiled!

Three modifying considerations, however, exist. These are first, nearly three-quarters of oil and gas enterprises are nationally owned bodies and not privately-owned corporations. Second, coal is most at risk, because it produces relatively greater carbon pollution. And, third, high cost properties are more likely to be put on hold than cost competitive ones like Guyana, as the 2020 crisis has revealed as it has unfolded.

Wood Mackenzie

In this Section, I refer to Wood Mackenzie’s recently published update of its reporting on estimated Guyana’s Government Take ratio, based on the existing PSA and the Stabroek Block operations. Its Q3, 2020 update is benchmarked within a “sample of ten countries with similar characteristics”. These countries are: Argentina, Barbados, Colombia, Guyana, Ireland, Jamaica, Mauritania, Somalia, South Africa, and Suriname. As stated in its release, these similar characteristics include payback periods, price resilience, governance and regulatory challenges facing the capture of government benefits, as well as state share in the sector.

The central showing is that Guyana’s terms fall in the mid-range exhibited by the ten countries in the sample. As Wood Mackenzie’s Director of Consulting is quoted as claiming at the Press Conference where the study was released, “Guyana’s terms are in the middle of the range for selected countries with 57% and a Brent crude price of US$40 per barrel in real terms” Indeed Guyana’s crude remains viable at oil prices less than US$40 per barrel in real terms!

The study also revealed that Guyana’s fiscal terms provide for a cost recovery time profile, which is shorter than average. This feature has long been the subject of strident criticism by the noise and nonsense echo chamber frequenting the country’s print and social media. The reason for this is that, if true, the truism comes into play: the shorter or faster the recovery period, the greater the benefit flowing to investors, IOCs.

As it turns out though, the Guyana difference from the average in the sample is minimal, only 0.1 year. The country’s PSA allows 8 years. The range in the sample is from 7.7 years in South Africa to 8.9 years in Colombia

Conclusion

Given the noise and nonsense echo chamber’s dismissive comparisons between Guyana’s fiscal regime and Suriname’s; that country ends up being the worst performer on the list.

Next week’s column will continue this discussion.