The most recent Pixar film, “Soul”, dropped on Disney Plus at the end of 2020 to bring some existential philosophising to the holiday season. In “Soul”, Jamie Foxx voices Joe Gardner, a middle-school music teacher living in a beautifully animated, realistically drawn New York City. Joe’s life whose life seems to be on the upturn when he lands a coveted spot playing in the band of jazz legend Dorothea Williams. The gig is the best news of his day. Even the announcement from his principal that he’s been made a permanent staff member earlier in the day cannot compare. As he scuttles off from his audition in glee, he falls down a manhole, therein ending that hitherto great day and sending us on the beginning of an existential adventure.

He does not die, though. At least not, yet. His soul, en route to the Great Beyond in some kind of non-denominational afterlife, tries to escape back to earth and he ends up in another part of the afterlife – in the Great Before, where he must use all his cunning to return to earth. He’s not ready to die. His life is only now beginning. He’s so close to his big break. But he needs to get through the Great Before, a stylised place that features two-dimensional, seemingly shapeshifting beings where young souls are mentored until they find the spark that will propel them to a happy and productive life on earth.

Joe, realising that this is his best chance to return to earth, assumes the identity of a Swedish psychologist tasked with mentoring an impish soul, 22, who has been languishing in the Great Before for centuries – resisting tutelage from some of the greatest minds in history. For Joe, his ability to fix 22’s blasé outlook on life, just might trigger a miraculous chance for him to return to his former life.

Conceptually, it’s a lot. But, despite the potential abstrusity of that log-line, “Soul” is never hard to understand. Pixar’s mode of selling existentialism to audiences through animation and humour is a well-worn staple at this point. It’s so well worn, in fact, that the script (credited to Black playwright Kemp Powers alongside Pixar stalwarts Mike Jones and Pete Docter) manages to sell the cerebral hijinks of this post-death world with more surety and sincerity than it’s able to sell us on to the emotional journey that Joe takes 22 on. So much so that when “Soul” ended the question that kept reverberating was not about the logics of its philosophy but something even more simple – who is Joe Gardener?

The 2020 premiere of “Soul” distinguishes it as the first Pixar film to feature an African-American protagonist. It’s gives the film an added significance that considering it without contextualising that fact of blackness amidst Pixar’s oeuvre feels incomplete. The title of the films seems to recognise this. Beyond the existential nuances of the world, ‘soul’ means a lot for Black America – the music, the food, the culture. Soul, as a word, is tied to ideas of blackness that feel essential. So even as “Soul” might emerge as just another in a long line of Pixar films meant to bring emotional catharsis through animation, its place as a text about black – or engaging with the idea of blackness, feels significant. And it matters, then, that “Soul” feels more engaged with the concepts that propel its plot than with the characters within that plot, particularly the ostensible protagonist Joe.

We meet Joe as a teacher in school, trying to muster enthusiasm for music from his classroom of students. They are unmoved by his enthusiasm, except for a solitary student. It’s that awareness that his enthusiasm is not easily transferred that marks the news from his boss that he’s been made permanent. It’s hard to share your love if it’s not received. It’s the reason his subsequent audition with Dorothea Williams, where he plays a beautiful extended piano sequence, feels so moving. Yes, finally. His music is somewhere where it can be appreciated. But as “Soul” goes on, it seeks to illuminate Joe’s life. And with that illumination comes a recognition that Joe’s relentless focus on music has eclipsed the other parts of his existence that he has not examined. And then the film makes the same missteps, because its own engagement with Joe feels unexamined.

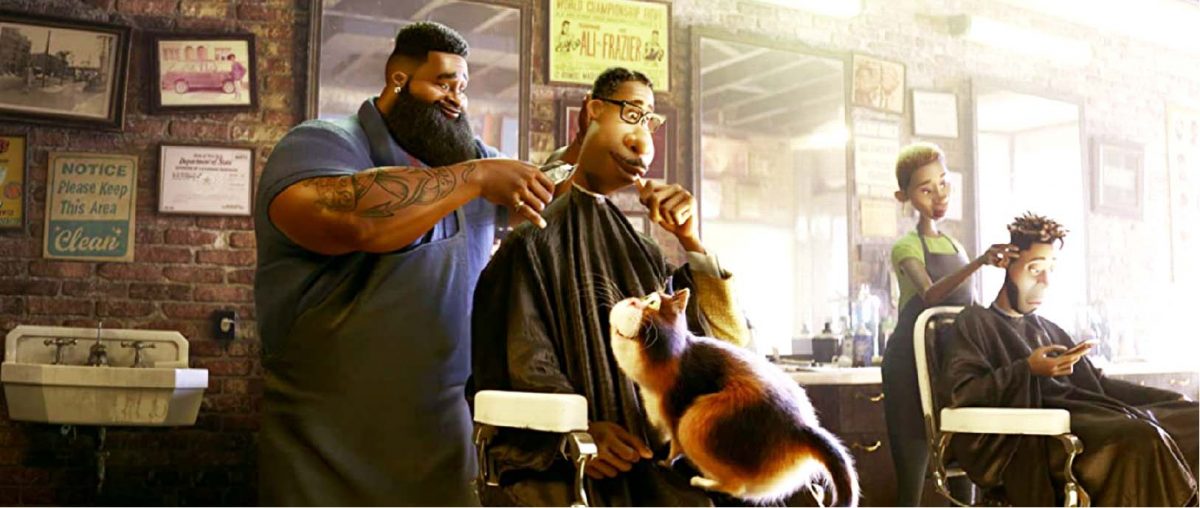

In a comic twist Joe and 22 end up on earth after escaping the Great Before but Joe’s soul is accidentally bonded to a cat and 22 ends up in Joe’s Body. The film’s swerve into a body-switching comedy is engaging but begins to complicate the ideas of Joe’s character development as 22 (voiced by Tina Fey in a self-conscious bit of casting that acknowledges that although 22 is not a persona she sounds like a white woman) begins to carry the emotional heft of the story. It’s vaguely unwieldly, as yet another animated film that places its black protagonist in the body of an animal for much of its running time, but here it seems even more complex as 22’s soul utilises Joe’s body in ways that Joe seems incapable of. As the film becomes a buddy-comedy, the script seems uncertain whose emotional journey we should be tracking. Plot-points suggest that it is Joe, but in three key moments (a barbershop scene, a visit from a student, and a confrontation with Joe’s mother) it feels like 22 is the one precipitating the film’s engagement with emotion.

Towards the climax, there’s a montage where we see a series of key moments from Joe’s life. It comes at a moment when Joe has an epiphany about who he really is. But the moment feels out of place. For that montage to work, we need context. We spend so much time with Joe’s soul, and yet the montage feels like a key that’s missing that cares to explore Joe’s life. The final twist of the film, which I will not spoil, depends on understanding a final decision that Joe makes. But the final act of choice for Joe feels hollow when the care put into the philosophical engagements overshadow any curiosity about Joe’s interior life beyond the broadest strokes. We need to care about Joe, and we need to understand Joe. But in “Soul”, Joe feels like an ancillary part of his own story. How do we come to care about a life that feels elusive?

The concepts at work here are fascinating, and the potential discussion points that soul might create are legion. But as a film about people “Soul” feels more ambivalent. There’s sincerity in the craft, the music (from Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross paired with Jon Batiste) and there’s attention to detail that’s clear. But “Soul” cannot make its discrete parts work as a whole of something when it feels like it is stuck in its own “Great Before”.

Soul is streaming on Disney Plus