Contrary to our hopes for this year, the spectre of 2020 has followed us into 2021. The COVID-19 pandemic is still raging on across the world, and now a new, more infectious mutation of the virus that forced England into lockdown has already jumped borders and oceans.

The year is already off to a bad start.

But there is hope!

Currently, there are three COVID-19 vaccines and they are already being used to combat the disease and late last year, our government also noted that it has put provisions in place to get enough vaccines for 20% of the Guyanese population and that these vaccines will be available to the public for free. This is good news.

While I understand that many of us want to put 2020 behind us for good, I fear that we may individually and collectively forget the important lessons 2020 tried to teach us. Even after the pandemic subsides and we put this disease behind us, we have a lot of work to do to rectify the health, education, and socioeconomic inequities the pandemic so aggressively displayed. We must also fight both misinformation and disinformation, since misleading or botched messages about the disease – for example the myth that young adults and children were ‘immune’ to the virus – most likely contributed to many unnecessary infections and deaths.

As we move forward in the new year with hopes of a ‘return to normality’, I want to keep the health lessons of 2020 in mind. We can only improve if we keep these lessons in mind and develop a wholesome, equitable, global culture around health so that we can make strides to prevent another 2020 from happening again soon.

The free short story collection, Take us to a Better Place, which was published in January 2020 by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, offers some insight into how we can develop such a culture. According to Pam Belluck, who wrote the introduction, the collection covers the physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of health through real-world, present stories and speculative tales about what the future may hold for us.

Reading this collection at the end of 2020 was a surreal experience as many of the speculative stories within it transformed into our lived reality over the last year. Others seem ready to become our future if we do not put measures in place to secure our future. This collection was not all doomsaying, however. Each story offered a glimmer of hope and a roadmap to potential solutions to a few of our health issues.

I want to focus on three of the stories whose lessons I want to carry with me throughout 2021. These stories are:

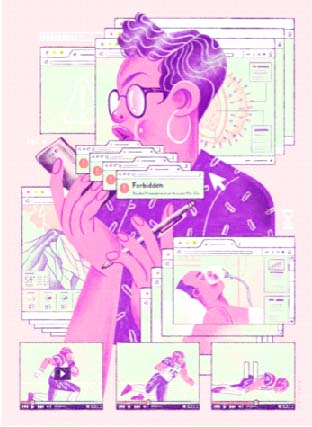

● “Viral Content” by Madaline Ashby

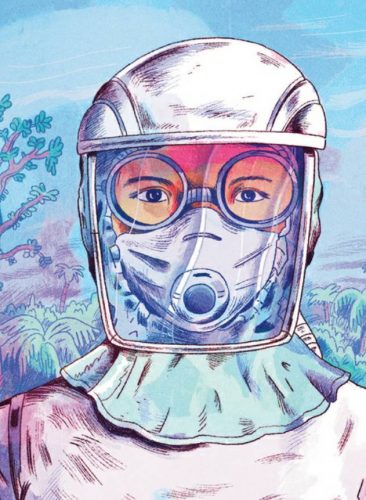

● “The Plague Doctors” by Karen Lord

● “Flotilla at the Bird” by Mike McClelland

Unsung Heroes: Health Journalists and Researchers

The first two stories I want to cover are quite similar. Both “Viral Content” by Madeline Ashby and “The Plague Doctors” by Karen Lord pay homage to the unsung heroes during health crises: health journalists and the global network of scientists racing against the clock to find the cure for the diseases.

“In an era when the facts don’t seem to matter, the relationship between a free press and public health is more important than ever. With this story, I wanted to explore how the future of journalism might impact the future of public health.” – Madeline Ashby, pp 295-296

“Viral Content” follows the work of a Gloryanna, a freelance journalist living in Tacoma, Washington. She is trying to uncover the details around the death of a star high school football player who died suddenly of the flu. She gets a lot of pushback from her editor, a representative from the media conglomerate for which she writes. Not only is her editor blissfully aware of the mortality rate of the common flu, but she also thinks that the politicisation of “controversial” health-related keywords like “vaccine” may put the company at risk of cyberattacks or worse. Gloryanna manages to get permission to pursue the story, only to find carefully constructed PR walls of silence intended to cover up a much bigger story that extends beyond the schoolroom and the playfield.

Last year, we saw how misinformation could rapidly overtake facts in the middle of a crisis when things are uncertain. There was even a quote in the story that is an eerie reflection of what my WhatsApp messages started looking like in the middle of March:

The last time a major flu outbreak had hit the community, the PTA was up in arms about it, and social feeds were alive with mommy bloggers hawking raw vinegar cures. (p.198)

Therefore, we should praise the journalists and media-savvy health personnel who took up the mantle to help push back against the misinformation. When things get back to “normal”, we also need to invest more into journalism so that our health reporters and media personnel can continue doing this work and that they can be better prepared to fight misinformation should something like this happen again.

I wanted a story about how those on the margins—isolated, overlooked, and underestimated—can still survive and even thrive. Thanks to Dr. Adrian Charles for helping me get the medical details right, from patient counselling to plague transmission, in the fictionalizing of a concept we have discussed before: the decentralized, modular, self-sustaining provision of health services. – Karen Lord (pp. 299-300)

“The Plague Doctors” also pays homage to heroes, but in this story, the focus is on researchers’ battling to find a cure for a deadly pox.

Dr Audra Lee is one of the plague doctors on Pelican Island, a small island disconnected from the mainland of some larger continent. While the pox ravages the rest of the world, Pelican Island is relatively safe from the plague, until the bodies of the pox-afflicted start washing up from the mainland and bringing the disease to the island. Patient zero is Dr Lee’s own niece, a six-year-old girl who – despite not showing any of the worst symptoms of the disease – is forced into six months of affectionless quarantine while her aunt and her team of researchers work alongside a global network of doctors and researchers from other isolated communities to find a cure.

This story covered some of the most frustrating issues the Caribbean faced during the pandemic: isolation, the impact of the rise of medical nationalism and plutocracy, and the constant barrage of conspiracy theories circulating across social media.

“Beyond all conspiracy theory, what if the silence from the mainland, and the missing journalists, and the darkening corners of the web were only partly due to the plague? What if there was a cull—not a purposeful, engineered attack, but a carefully curated neglect? Keeping the best chances of prevention and cure for those who could afford to pay for it…a kind of plutocratic manifest destiny.” (p. 247)

But this story was not just about the problems, but solutions. Although Pelican Island was untouched by the plague for what seemed like weeks or months, when it finally hit the island, its citizens and health personnel were ready to spring straight into emergency mode which kept the numbers of infections on the island down. The plague doctors on the island were also instrumental in the global drive for a solution, which seemed to be a reference to CARICOM’s leadership in the global fight against non-communicable diseases.

What also made the story interesting was its beat-by-beat accuracy to the 2020 pandemic timelines. When I spoke with Karen Lord, she noted that not only did she name Pelican Island after the real quarantine island off the coast of Barbados, but she hired a medical consultant to more accurately represent the local and global impacts a pandemic might have. As such, even she was surprised by the startling accuracy of the short story. If the ending is anything to go by, however, I also have hope for future solutions in disaster management.

“The Flotilla at Bird Island” and hope for the new year

I wanted to imagine a community of people in which health equity had been achieved, and how starkly such a community would stand out in a future shaped by climate change, poverty, and discrimination—and that’s how “The Flotilla at Bird Island” was born. – Mike McClelland (p. 300)

Take Us to A Better Place takes us on a journey of dystopian predictions about the future of global health, all based on current trends, and covers some very depressing topics. “The Flotilla at the Bird” by Mike McClelland is no exception, but it also gives us a glimpse of what a utopian vision of health care could look like. In this story, climate change and sea-level rise, pollution and ozone depletion jointly contribute to the severely reduced health quality worldwide. Cancers and uncommon viral and parasitic diseases are now commonplace and health officials and workers constantly scramble to keep the American population immunised against more aggressive forms of these illnesses.

However, there is a hope swirling around two friends, Kyle and Bobby, when they meet at a bar in Atlanta for lunch. Bobby is a rich philanthropist and Kyle is a successful musician in Atlanta. Kyle is depressed by the chaos of the world around him and Bobby, through his own initiatives, has thought of a way to pay reparations for both himself and his rich ancestors and colleagues whose greed helped to plunge the world into chaos.

In 2020, the world’s billionaires grew richer during the pandemic, and a recent report by NBC news noted that Wall Street minted 56 more billionaires since the pandemic began. Meanwhile, poor and middle-class workers struggled as the pandemic upended their livelihoods and securities. It is infuriating to know that there was enough money and resources to cushion the blow of the pandemic on the most vulnerable. Sadly, much of these resources were channelled toward the rich to appease their greed.

McClelland’s gentle narrative makes a radical suggestion by having his billionaire character step up and take full, practical responsibility for global health. Rather than hiding away in a bunker and waiting for the world to finally end, he turns his bunker into a space where the seeds for a better, kinder, more equitable world can be stored and planted and tended in the future.

Hope in the face of adversity is critical, especially now. Reading this collection at the end of 2020 was difficult because of how familiar it was. Regardless, I believe that these stories – even though they are fictional accounts – can serve as a basis for a roadmap which can Take Us to a Better Place: a more health-conscious, equitable future. Admittedly, this is a dream that is more easily written than executed. Therefore, as a local, regional, and global community, we need to push to ensure that systems are implemented at all levels to ensure 2020 does not repeat itself.

To read or listen to the audio edition of this collection, you can click here.