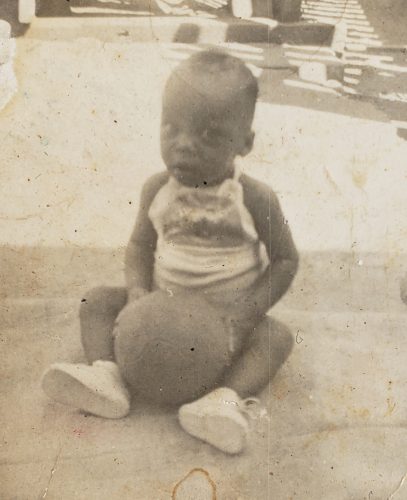

“Football was to be my destiny,” says Gordon Winston Patrick Brathwaite, 62, recalling that when he was just 18 months old he was photographed with a football.

Now a national football coach, vegetarian chef and poet, Brathwaite believes God used football to keep him away from crime and he has in turn used his own skills as a footballer and chef to steer the young people under his supervision in the right direction.

“For 46 years I have been coaching school club and then national football and helping players to find their way in life. I am privileged to have made an impact in helping the development of football in Guyana, and in using my position as coach and chef in my social work to keep many young people off the streets,” he told Stabroek Weekend during a recent interview.

Speaking about his love of football and where it has gotten him, Brathwaite said he started playing football at Queen’s College (QC) in 1969 at 12 years. He played in the Under-15 and Under-18 inter-schools football competitions. He was the captain of QC’s junior and senior teams from 1970 to when he graduated in 1973. “That was when I started making my name as a footballer. Then schools football was vibrant and inter-schools and inter-clubs competitions and schools football were well organised.”

In August 1973 he was not included in the Guyana team for the Inter-Guianas Games (IGG) because he had just graduated and the headmaster did not sign for him as a student. In 1974, he played for Guyana in the IGG in Suriname. Past students can now represent a school for a year after leaving.

On leaving school, he joined Pele Football Club, one of the leading clubs of the day. “That was where I made my name and fame. When I joined Pele it was very hard for me to make it because of the good quality of players. I started playing for Guyana on September 15, 1975 as an Under-18 player. Two years later on the same date I made my senior debut for the national team before I was 20 years. When I heard the National Anthem playing for the first time as a national player, my skin grew. I saw myself as nobody to being somebody.”

Temptations

“Football and God Almighty stopped me from being a criminal. My mother, who was my motivator, insisted that I go to church regularly. We lived in Howes Street, Charlestown. I was born in Bent Street opposite the jail. Mom told us at an early age that none of us must go in there. None of us did.”

Nevertheless, he was tempted. Unemployed during the 1976 Christmas season, he said, he and another fatherless youth decided to raise money. (Brathwaite’s father, Inspector 4412 Whittington Brathwaite, was one of five police officers killed by rebels of the January 2, 1969 Rupununi Uprising. He was the officer-in-charge of the Lethem Police Station.)

The two decided “to go for a hustle on the road but I resembled my father,” Brathwaite said. A policeman who recognised that the two were up to no good, hollered ‘Young Braff!’ as a warning.” After that he went out a few times with the boys. “Every time I tried to do something bad, the Spirit used to tell me, if you thief you can’t play football. We used to train at Eve Leary so some of the police knew me. On another occasion when I was tempted, a policeman stopped me and asked me if I was 4412 son. It was like God used to put a policeman on the road to stop me from doing bad.”

In depressed communities, he said, “The temptation to do wrong is always there. No one is there to tell you not to do it. Most times, parents are out trying to earn a dollar and the children grow up looking after themselves. That is why a lot of youths from these areas become involved in crime.”

Even now, he said, “Because I am a Black Rasta man people would associate me with things drugs-related. I don’t do drugs.”

After his Christmas 1976 temptation, Brathwaite said, “On Old Year’s night when everyone was partying, I started training at the corner of Howes Street. When the clock struck 12, it was me and the ball. I used to pray just to make the national team. I also broke the year 1977 training and made the senior team that year. At the end of 1977, I was the footballer of the year and runner-up sportsman of the year to cricketer Colin Croft.” Both Croft and Brathwaite were from Howes Street.

In 1977, Brathwaite started working for Guymine/ Guystac as a clerk. At that time Guymine (Guyana Min-ing Enterprises) and Guystac (Guyana State Corporation) organised big sporting tournaments.

“A lot of the sportsmen, including footballers who represented Guymine or Guystac were national sportsmen who were employed by these companies.”

In 1978, he obtained a scholarship to Clemson University in South Carolina but only spent a year. He made the Dean’s List in academics and played in the Atlantic Coast Conference soccer league. Three teams from the university were picked to compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division One men’s soccer (football) tournament. “I was the only freshman to make the first team.”

In retrospect, dropping out of university after the first year, he said, might have been a bad decision but at the time he thought it was wise for several reasons. “The North American Soccer League of professional footballers was getting big but they were only hiring players from established football countries. Then I became a Rastafarian and started growing my locks. As a Rasta, I knew I would not be able to get a job in football in the US back then. I was majoring in Spanish with French as a minor. As a Rasta, I knew I wouldn’t have gotten a job in the diplomatic community either. I made up my mind to return home and contribute to football in Guyana as a player and as a coach. I was not deported as some people would like to believe.”

On return to Guyana, Brathwaite began in earnest to play on the national senior team and to coach.

“For years, I coached without getting paid and without a salaried job. At one time I was living on handouts from football friends living overseas because I lived for football.”

Brathwaite said he was stopped from playing and captaining the Guyana team when he was 27 years at the peak of his career due to the politics of the sport. “I last played and captained Guyana against Suriname at the GDF ground on 27th March, 1985. The Guyana Football Federation (GFF) said they were trying to get a new team. I was forced out of the national team. The country lost a lot of football from me. I, as captain on the field, and the coach who was off the field, could not see eye-to-eye many times on strategies. I lost my place on the national team because I talked my mind. I then played club football until I was 50 when I still scored.”

After the GFF dropped the national team age to under 25, Brathwaite said, President Forbes Burnham had recommended that one of the best ways to resuscitate the Young Socialist Movement (YSM), then the youth membership of the party in government, was through football and sports. He believes that the football authorities wanted to stop him from playing hence they recommended that he be given the task to form the YSM Beacon. Under his leadership, the YSM Beacon became a force to be reckoned with.

After Brathwaite worked with the YSM Beacon for a few months, the GFF reverted to its former age policy. “They tried to give people the idea that I was only interested in coaching for the money and not playing.”

As the YSM Beacon’s coach, Brathwaite was paid through the Office of the President. When the PNC government lost the election in 1992, his job was rescinded.

“I subsequently worked as a national coach with the Ministry of Sport for a year and then trying to be fair-minded, I was fired. People do not like you to tell them that wrong is wrong. In the name of discipline, they want you to always say ‘yes’ and toe the line. Now, since 2018, I am a national coach again.”

During his current tenure at the sports ministry, Brathwaite has held coaching sessions in several Indigenous Peoples communities, including Baramita and Paramakatoi. After training sessions, he would broach “tabooed topics” with players to help them cultivate healthy minds and healthy bodies, especially in Bara-mita, which is plagued by many social ills.

In 2019, for the first time under his guidance, Paramakatoi won the North Pakaraimas tournament. They had never made it to the finals before.

His concern, he said, is that staying for two weeks in the hinterland areas is not sufficient for mentoring and there is need for constant follow up.

Labour of love

Noting that football is the most popular sport in the world, Brathwaite said, “In Guyana, football coaches and footballers are treated like dirt. The authorities see football as a ghetto game. Only recently the national squad was paid some money owed to them years ago. Things have not changed much from the time the national senior team would camp at the GNS Sports Ground in the early 1980’s. At one time as the national captain I called on players not to gear up for training until their meals situation was addressed. Players were training between 5 am and 7 am and getting breakfast at 11 am, and getting lunch at 3 pm to begin training at 4 pm. Things like that were held up against me. This kind of treatment caused players to abscond in the US in 1987.”

After playing for Guyana for a decade, he said, he does not have a pair of trunks or shorts to show as a memento.

“My life is football but sometimes it frustrates me. I see young coaches who never played for Guyana making money because they humble themselves to other people.”

Through coaching, he said, he has steered many young people from getting involved in crime.

Even though he knows that sports go hand-in-hand with academics, he said because football is an amateur sport in Guyana, he asks players, and especially those from depressed communities, to give priority to academics over football. “Football is an amateur sport in Guyana. It does not pay.” He worked with many who took their academics seriously and moved out of the “ghettos” because of the jobs they later acquired.

“As a coach, I have to be big brother, father, uncle, secretary, counsellor and social worker. It is a labour of love. I have had to make sacrifices. I am humbled but satisfied that past players would remind me about some things I had done for them, like feeding them when they had nothing to eat. Like giving a player his first pair of jockstraps or a youth player a pair of brand name boots that renowned Brazilian footballer Pele had endorsed, or a track suit to motivate another player to score a goal in a crucial game.”

“God showed me that what you put in, you put out. When I started coaching, I prayed that if I get one person to emulate me and to play for Guyana I would have achieved. I have seen this in national player/national coach, Wayne Dover, who I coached exclusively.”

Over the past 30 years many good players passed through his hands including Gregory ‘Jackie Chan’ Richardson, Jermaine Scott and Anthony Stanton. “The first time Stanton scored for Guyana, I was his coach and he made it to the Shell Cup semi-finals.”

Among players he coached were his sons, Nkosi and Kayode. Kayode was a national youth captain.

“There is a possibility that I may be the first footballer in the Caribbean that was captain and coach of a national team in a World Cup qualifier,” he said.

Food and nicknames

Brathwaite always loved cooking and took to selling porridge and vegetarian meals to earn, or to supplement his income. “A lot of football players and coaches wouldn’t sell food and drinks to earn their living.”

As players would tell him they had nothing to eat before training, he would take porridge to the camps for them. “Once a manager told me to stop because it made the GFF look bad. That did not stop players from coming to my home to get food.”

George Humphrey, the owner of a bakery in Ketley Street, Charlestown, Brathwaite claimed, donated bread to the national team when he heard that he, Brathwaite, was picked for the national team. “Every time I made the national team, he gave me money. He was a big donor to football and he would say in his big voice that he was helping the GFF because of Ultimate Warrior.”

As a prominent athlete, Brathwaite was given many sobriquets, with ‘Coachman’ being the most popular. “I was called ‘Ultimate Warrior’ after the hero Yul Brynner [played] in the 1975-science fiction action-movie and after I had bald my head. They called me ‘Floato’ at QC because I was good at high jump, ‘King of the Air’ because of my headers in football, ‘No Sex’ because I had no girlfriend around football, ‘Criminal Face’ because I was always serious. At home I was called ‘Frankie’ because I talked my mind and got licks, and footballers called me ‘Black as Duh’ for plain talk. Some call me, too, ‘Rhyming Coach,’ because I write poems for all occasions and I can rhyme on the spot.”