By Eusi Kwayana

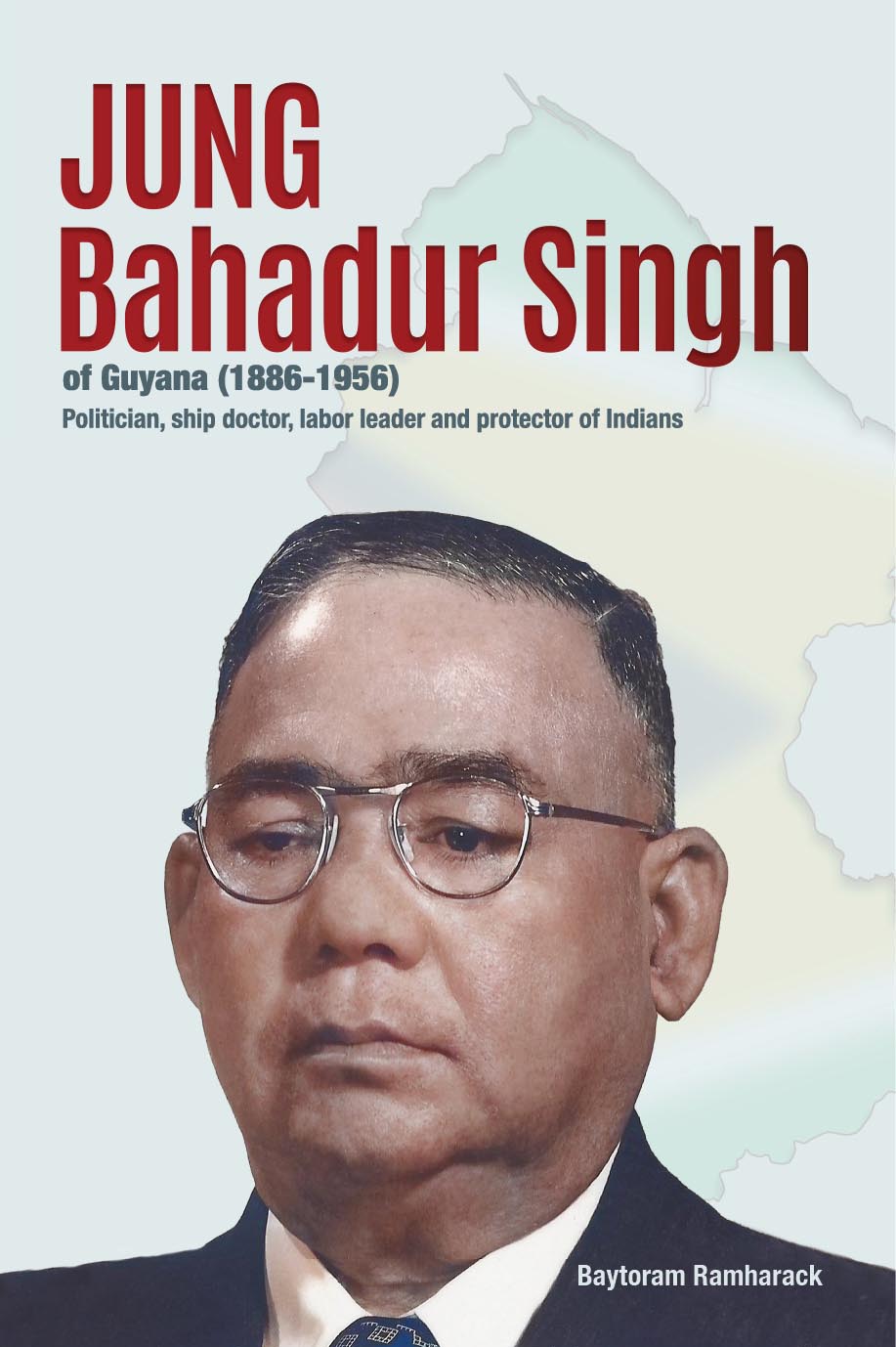

[Baytoram Ramharack, Jung Bahadur Singh of Guyana (1886-1956): Politician, ship doctor, labor leader and protector of Indians, San Juan, Chakra Press, 2019. 378 pages]

Dr. Baytoram Ramharack’s earlier biography of Balram Singh Rai treats the political life of an outstanding Guyanese villager who, in 1961, became Guyana’s first Minister of Home Affairs, with responsibility for Police. Rai’s formal parliamentary life began in 1957 and ended in 1962, when he lost favor with the ruling Peoples Progressive Party. The 1957 elections were the first to be held in the country after the suspension of the Constitution in 1953, during which period Guyana was governed directly by the Governor, who passed laws through a hand-picked Interim legislature. The present biography of Jung Bahadur Singh will take readers back to a parliamentary life that ended dramatically with the 1953 General Elections. Fortunately, it is not one based in narrow political activity, but one that was engaged on various fronts in a wider and deeper striving for human dignity and, in particular, the dignity of indentured immigrant workers and their families and other Guyanese.

Jung Bahadur Singh was born in 1886 at Goed Fortuin in West Demerara into a large household that had sprung from a union of Christians and Hindus. Although he belonged to a kind of underclass as a child of indentured labourers, the peculiar circumstances of Indian indenture allowed his marriage to be a prestigious event, taking place, as it did, in Paramaribo at the premises of the high-ranking Indian Immigration representative.

This review will differ from the typical writing of Indian history, or African, or indigenous history in Guyana, as it will introduce into the text glimpses of the complexities that have developed within the bosom of plantation society, well-known for its segregated spaces and for the despotic control exercised over it by a tiny white minority, able to rely on state power.

Jung Bahadur’s father was one of those individuals who could exploit gaps in the social setting and carve out a way of life which was not typical for the body of indentured workers. He became a tailor with his own sewing machines and, in time, he had established a line of product which he distributed over wide stretches of the country. The young child, Jung, attended an Anglican primary school and later a famous village school. Already influences, other than those of his Hindu tradition were at play, contributing even in minor ways to the person Jung Bahadur was to become. Taking his family history into account, it is not surprising that the youth was among the highly select minority to be engaged by compounders on ships plying between India and a number of colonial plantation countries in some three oceans to supply indentured labor to countries like Mauritius, Fiji, Surinam and British Guiana. This was a highly valuable experience for one who carried in his line names like Deenanath (defender of the poor), and was finally named after a significant historical figure.

The author notes that, as an employee in the compounding or sick-nursing services of these ships, Jung Bahadur came face-to-face with substandard arrangements for women on these vessels and with the physical indignities to which many of them were exposed. A sensitive mind could not fail to be impressed by such experiences and we can be excused for assuming that they played a part in his development as a social and political man of action.

Although Indian indenture ended in 1917, this reviewer, not yet born in that year, knew in his boyhood at least two sick-nurse dispensers that had served as compounders on immigrant ships. The route by which Jung Bahadur Singh moved from compounder assistant to compounder in his own right, and from compounder to doctor of medicine is noteworthy. He stayed on the ships for 12 years until the age of 28, when he ended his career as compounder. During his long breaks between trips on shore in Calcutta, the young nurse and apprentice dispenser wisely chose to enroll for pre-medical studies in Calcutta schools, courses which allowed him, it is assumed, to meet the requirements for enrollment in medical school in the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. The author notes that university education was for foreigners more affordable in Edinburgh than in London. This fact of affordability explains part of the biography of Guyanese like Dr. Frank Williams (MD) and H.H. Nicholson, multi-disciplined scientist, who both studied in Edinburgh. Both Jung Bahadur Singh and (decades later) Frank Williams had moved with their small families to Scotland for the duration of their student days there. Having qualified as a medical doctor, Singh returned to the land of his birth and, from all the records, began a life of purposeful activity that contributed to many changes for the better in the lives of Indians and other members of the various communities in which he chose to be active. He worked as a GMO and, as part of this function, he had much to do with the upgrading of services in the hospitals on sugar estates, which he covered. GMOs in those years were each assigned to a large district, which often contained their own clinics with Notice Boards and included plantation-owned hospitals, which the GMO supervised. Residents along the routes covered by the GMO knew how to secure a visit from the doctor by raising a small flag of a given color on the parapet to attract the doctor’s attention. Much can be said about the rich interchange of trained sick-nurses, dispensers and midwives that took place between villages, sugar estates and other settled communities. Outside of Georgetown, New Amsterdam, Suddie and other towns, the GMO would have a settled residence in a big house in a village where the GMO would be at the disposal of patients.

Dr. Singh, who is described as always having an interest in Hindu culture and religion following his preferred expressions of these, soon became involved in the newly formed British Guiana East Indian Association (BGEIA). The BGEIA was devoted to all-round improvement in the lives of Indians and had its parallel among Africans in the British Guiana Negro Progress Convention.

Dr. J.B. Singh served six terms as president of the BGEIA and was elected for a 7th term, which he did not serve. Of the numerous issues agitated and pursued by the BGEIA, this review will treat only three; namely, the Indian Colonization Scheme, the Swettenham Circular and voting rights, as documented in the Franchise Commission Report (1944).

In 1931, Dr. J.B. Singh became the first Hindu to be elected to the colony’s legislative council. The first Indian so elected was Mr. E.A. Luckhoo, representing New Amsterdam, where, significantly, Indians were a minority on the voters’ list. Dr. Singh was one of those change makers who, as Dr. Kimani Nehusi observed, were active both in race-based organizations and in organizations of a multi-ethnic membership.

Before leaving for medical studies abroad, Singh had been a student for two years (1898 – 1900) at A.A. Thorne’s Middle School, which Ramharack describes as the first co-educational school in British Guiana. This was another example of his nurturing towards being effective in a complex society.

As a member of the country’s law-making body, Singh brought discipline and seriousness to his work, making representations for his constituents and being able to list his successes in his election manifesto in 1953 as improvements in the people’s living conditions.

Although he had been a student in a co-educational school, Singh, under the influence of the traditional family, supported for many years the notorious Swettenham Circular, which modified the 1876 law, making primary education compulsory. It waived prosecution of Indian parents who prevented their daughters of a certain age from attending school. The Circular led to the opening of one of the sharpest controversies in education in British Guiana. The book under review names two leading Indians who kept this debate alive and public.

One was Mr. J.I. Ramphal, who strongly denounced the Circular as harmful to Indian development. The other was Dr. J.B. Singh, who defended the Circular and saw it as being in harmony with Indian traditions. After some years, Dr. Singh conceded that holding on to Indian traditions about education of the female would be unhelpful to the Indian section of the population.

Ramharack cites a letter to the editor, written by Singh in 1935, in which Singh, reflecting on the Ruimveldt riots of 1924, expressed the opinion that the British Guiana Labor Union (BGLU), with its predominantly African membership, could not adequately represent Indian sugar workers, a growing majority on the sugar plantations. Yet, history recalls in many places that the BGLU, in its early days, was the only organization giving effective labor representation to sugar workers. Such was their satisfaction at that period that they nick-named H.N. Critchlow “Black Crosby”, after an Immigration Agent General, whose service to their cause met the approval of the workers. Critchlow and Singh were to have another disagreement during the debate in the Legislative Council on the report of a Commission appointed by the Governor to report on changes in the right to vote in general elections. Critchlow had been a pioneer in the call for adult suffrage, the right of all Guyanese, without exception, to vote at age 21. However, by the time the Franchise Commission Report came to be debated in 1944, developments had brought about changes in social relationships and perceptions. These changes affected the race class attitudes of political sectors and some of their representatives. It appears to this reviewer that one of these developments was the introduction into the political process of what has been called the Indian Colonization Scheme. The other was the Franchise Commission Report and the debate on it in the Legislative Council. The two issues were inter-related, although they occupied public attention at different periods of time.

Just about the time Ramharack’s new biography was about to appear on bookshelves, there was a publication in the Guyana newspapers of the reprint of a document with a brief introduction by Dr. Eric Phillips, the chairperson of Guyana’s Reparations Organization. The document itself included excerpts from British Guiana’s governing organs, recording developments during the time when the Colonization Scheme was being actively pursued. The excerpts bore the signature of Jonathan Adams of the Reparations group.

Responding to the publication described above, Jung Bahadur Singh’s biographer, in a letter to the editor, directly asked Phillips to explain his “motive” in issuing the publication about issues which Phillips himself had said had not attracted much attention when they were current in the first quarter of the 20th century. The book under review itself contains evidence that the Colonization Scheme attracted the well-deserved attention in the private and public concerns of the Indian and the African ethnic organizations. The governments of the United Kingdom, India and colonial British Guiana were also actively and openly occupied with the issues. So also were organizations of the Planter class. To assume, as has been assumed, that writers of history have ignored the issue and context of the Indian Colonization Scheme is an unfortunate error. In actual fact, its place in public affairs was so weighty that it led to official delegations being exchanged among Britain, India and British Guiana. Evidence of this claim is not hard to find.

In this reviewer’s papers to the 1988 International Commemoration Conferences in Georgetown, he explored the effect of the Indian Colonization Scheme on the domestic political situation in British Guiana. In doing so, he relied partly on a small book by Mrs. Edith Brown, widow of the lawyer, Den Amstel’s A.B. Brown, who was the first African to be elected to British Guiana’s law-making body. From her book and other sources, it appears that the African organizations did not oppose the Indian Colonization Scheme, but thought to introduce an African Scheme, relying on migrants from Liberia. The colonial office allowed the Guyanese Indian delegation to visit India, but disallowed the visit of the Guyanese African delegation to Liberia.

Thus, it is clear that inter-ethnic relations in Guyana have never been the results of mature relations among the groups. They have always been influenced by manipulation by the colonial command, which placed its own interest first. The author, in his letter referred to above, shows awareness of this Command and must know that it had always been decisive in our affairs. Even as this is being written, Guyanese political sectors are showing their readiness to invoke, or warn against, geo-political pressures.

In celebration of his remarkable efforts and his dedication to both the race that gave him birth and the country that was his birthplace, let it be said that J.B. Singh found ways of allowing his talents and expertise to serve diverse communities. This reviewer selects the following examples:

There is the record of the seven times he was elected president of the BGEIA. He had become a member of the British Guiana Workers’ League. He became a trustee of the Man Power Citizens’ Association. He became the first chairman of the multi-ethnic British Guiana Labour Party. Most significantly, he founded the British Guiana Nurses’ Association.

J.B. Singh’s interest in culture included not only practice of the traditions laid down by Hindu sages and the observers of seasonal and functional rituals. His conspicuous residence in Lamaha Street, Georgetown became a nursery for the fine arts in Indian idiom and flavor. His wife was a recognized producer of theatrical works. His daughter, Rajkumari Singh, despite her disability, has been applauded as an archive and producer of what she proudly called “Coolie Culture”. The author named three gifted artists, Gora Singh, a dancer, Mahadai Das, a gifted poet, and a novelist, Rooplal Monar.

The author concludes his very timely and instructive biography with a chapter captioned, “The Rise and Fall of Jung Bahadur Singh”. This title, in the reviewer’s opinion, is misguided. Since he did not present himself as a man of destiny, but as a qualified human being serving necessary causes, the cliché, “Rise and Fall”, does not fit the case. Rather, Dr. Singh’s defeat was influenced by the new political process and organization of 1953, which worked in such a way that Singh was defeated at the polls by an unknown, but intelligent, shovel man, Fred Bowman, of the PPP. While Dr. J.B. Singh practiced a political culture of service in mass organizations, together with working in secret committees as a member of the Governor’s Executive Counsel, the role of the PPP was public exposure. In the 1953 elections campaign, Dr. Singh’s chief tormentor was Pandit Misir, who regularly exposed Dr. Singh to ridicule by claiming that the member sat on the chairs of the Legislative Counsel uselessly like a “Christmas Father”. Pandit Misir’s claim to fame was that he organized the Yag at Vreed-N-Hoop to be addressed by Mrs. Janet Jagan, causing her to be charged with a breach of the emergency regulations and jail. This trial was the occasion of her famous statement about her origins and faith, which has brought criticism to those who have dared to quote it. During the Yag conducted by Pandit Misir, voices accused the Pandit of reading wrong.

In terms of cultural history and experience, Dr. J.B. Singh, far from rising and falling, was absorbed into the infinite heroically. His body was the first to be officially granted the rite of cremation, for which Dr. Singh had struggled for decades.