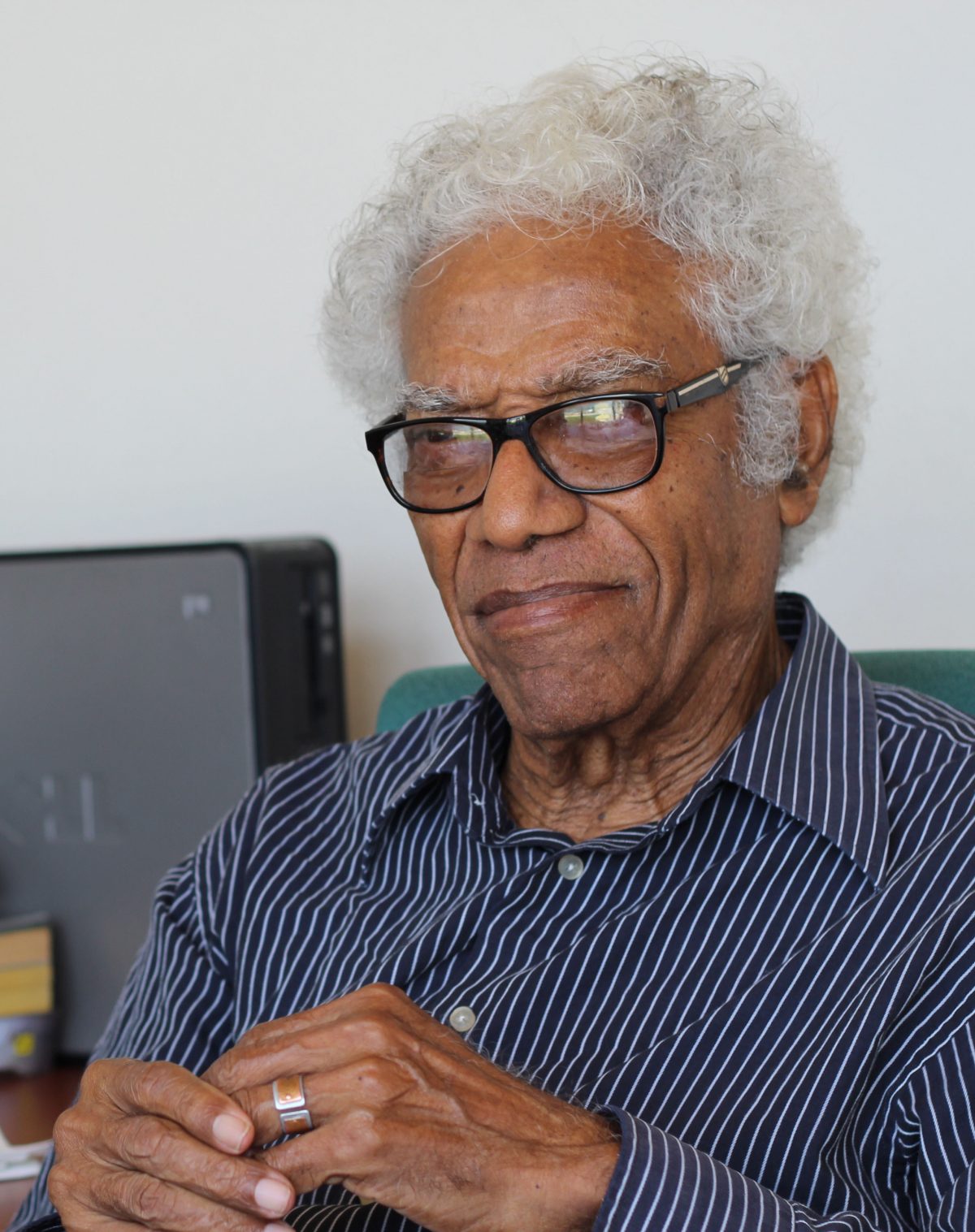

George Lamming is among the Caribbean writers who have contributed to the building of its nationhood through entertaining story-telling in fictional narratives, deep and ever-relevant scholarship, and interventions in regional thought and philosophy. Lamming, who celebrated his 94th birthday on Tuesday, June 8, 2021, was born in Carrington Village, Barbados in 1927. He worked as a teacher in Trinidad from 1946 until he migrated to England in 1950. As part of the legendary Windrush Generation he was among leading West Indians, labourers and writers alike, who went into exile to develop their careers and were responsible for the main thrust in the rapid growth to prominence of West Indian Literature in London in the 1950s.

The MV Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury in England on June 22, 1948 landing 492 passengers – workers from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and other West Indian islands — who, according to the BBC (July 31, 2020) arrived “to help fill UK labour shortages”. That was the start of the historic migration to the UK, which also saw arrivals from India, Pakistan and Africa, and the root of the “Windrush scandal” which broke in April, 2018. It saw “the UK government apologise for deportation threats made to Commonwealth citizens’ children. Despite living and working in the UK for decades many were told they were there illegally because of a lack of official paperwork”, according to the BBC.

But that was only the latest in a history of scandals that followed the Windrush, concerning race relations in the UK. The stormy existence of these immigrants was taken up by Lamming in his fiction and non-fiction. It is significant that this post-war exodus also gave rise to the development of one of the most important literary movements in the modern world – post-colonialism. It was born of migration from Commonwealth countries, former colonies in the British Empire, the UK experience, the quest for independence among those nations, and what all that reflected in the style and preoccupations of the writers at home and in the UK.

One of Lamming’s travel companions in 1950 was Trinidadian Sam Selvon, who Lamming said showed him the unfinished manuscript of the now famous novel, A Brighter Sun. VS Naipaul, also in 1950, Jamaican Andrew Salkey, and Guyanese Edgar Mittelholzer at other times were also members of the Windrush generation. Because that movement was not only responsible for post-colonialism, but for the concept of exile, which defined the most important period in the march to prominence of West Indian literature. Most of the major players in the rise of this literature were fellow migrants with Lamming seeking to build their careers in a land of opportunities which was as ironic and deceptive as Lamming perceived and described in his non-fiction writings.

Highly decorated as a novelist, George William Lamming started writing as a poet. His considerable impact on world literature was deepened through his literary criticism, his consistent contributions to Caribbean post-colonial thought and the philosophical underpinnings of regional poetics and historiography. Much of this is underlined in his ground-breaking non-fiction publication, The Pleasures of Exile (1960), whose ironic title and occasionally controversial commentary set the record straight about the concept of exile and the emergence of a great literature. This remains Lamming’s most critical intervention which contains his unforgettable declaration that “English, after all, is a West Indian language”.

The Pleasures of Exile remains a major intervention in Caribbean criticism because and in spite of the date of its production, early in the era of the developing literature. It had no prescriptions to follow, and some of its judgments – in particular his criticism of Naipaul — were fairly premature. Yet Lamming got it right in his post-colonial positions. Highly acclaimed among his critical interventions was his allegory of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, casting the Prospero-Caliban relationship as the West Indian colonial experience. Yet he claimed the language of the oppressor as his own, enlarging the position that England had no monopoly ownership of the English language, a medium used, beside the Creole, by the Caribbean’s major writers. He saw English as Walcott also came to do, as a language of West Indian literature. Adopted by some radical thought, Lamming’s is also the position taken by the region’s contemporary linguists.

Lamming’s place in the literary world is immovably entrenched by his continuing quarrel with history, as a critic and as a novelist. The first of his six novels, also emphatically ground-breaking, is In The Castle of My Skin (1953), which is autobiographical. It speaks about growing up in the West Indies, telling the story of colonial education, village life in Barbados, and the quality of pre-independence colonialism in the Anglophone Caribbean.

The novel bears another of Lamming’s ironic titles, and is taken from the very early work of Walcott, Epitaph for the Young: XII Cantos (1949). The lines of Walcott’s poem are, “You in the castle of your skin / I the swineherd.” The hero is a boy named “G” in what critic Sandra Pouchet Paquet calls “autobiographical novel of childhood and adolescence” in the 1930s – 40s. It starts on his ninth birthday and ends on his departure for Trinidad to work as a teacher. The exact journey was taken by Lamming at the age of 19. It is the type of novel common among West Indian writers up to the present time. The coming of age of the hero is indistinguishable from that of his native land under colonialism, and includes several post-colonial ironies and subtleties of which Lamming became aware on his journey into London alongside Selvon.

In The Castle of My Skin (first published, Michael Joseph, London, 1953) is highly celebrated. Lamming says of it: “The novel was completed within two years of my arrival in London. I still shared in that innocence that had socialised us into seeing our relations to the empire as a commonwealth of mutual interests”.

The novel Water With Berries (1971) continues the quarrel with history waged by a writer perpetually conscious of a people’s need for liberation and their relationship with the colonial experience. The title also has intertextual resonance, not without the usual ironic approach. It resonates with a story told about Columbus’ arrival in the Caribbean. After sailing for an unbearably long time without arriving at his intended destination, the explorer was facing rebellion among his men. But in the very nick of time he saw floating on the water, a little branch with berries on it, which indicated to him that land was near. He was right, and so they made their first landing. Columbus proceeded thereafter to claim islands in the name of the King and Queen of Spain. Since his plan was to prove that he could get to India in the east by sailing west, the islands were called the West Indies.

Lamming has had reasonable association with Guyana. He once served as a member of the Jury of the Guyana Prize for Literature. Long before that, he was deeply involved in The New Word Quarterly in Guyana, a companion journal to literature, politics, and society in the West Indies (1963 -1972). The New World group had its origins in Guyana in 1963, but in some years struggled to keep up its publication because of funding. The journal ended up on the Mona Campus of UWI in Jamaica. Among the associates in Guyana were David de Caires and Miles Fitzpatrick who kept up the publication and according to de Caires, invited Lamming to work with them on issues, particularly a panned independence issue in 1966.

Other Lamming books include: The Emigrants (1954); Of Age and Innocence (1958); Season of Adventure (1960); Natives of My Person (1972); Coming, Coming Home: Conversations II, (1995); and Sovereignty of the Imagination: Conversations III, (2009).